A Different Set of Gallos: the Bonannos, the John Bazzano Murder, & the California Bay Area

The Sicilian Gallo brothers reveal the scope of Cosa Nostra's national connections and the treachery of its evolving governing bodies.

I take special interest in lesser-known Cosa Nostra members. These men are otherwise footnotes in larger figures’ stories but further investigation reveals new information about the mafia and its history when we zoom in on the details surrounding these individuals’ lives.

Sometimes a “footnote” member shows up in connection with a significant person or event in Cosa Nostra history but has no signs of sustained importance in the organization. They disappear into dormancy for periods only to show up again in connection with another person or event, returning back to the shadows afterward. When we manage to find out more about these individuals we discover they have a story worthy of being told, too, and this story tells us as much about Cosa Nostra as it does the individual.

This is particularly true for Bonanno Family member Ciro Gallo, who was directly connected to two noteworthy mafia murders on opposite coasts during the 1930s and 1940s. Research reveals there is far more to his background in Cosa Nostra and it includes other significant names worth exploring in-depth. This article is a winding analysis exploring the evolution of American Cosa Nostra with Ciro Gallo coming and going, just as he did in life.

From Sicily to New York via California

Born in 1898, Ciro Gallo came from the small Palermo village of Palazzo Adriano and entered the United States through California via Tijuana in 1927. By the early 1930s he moved to Bushwick, Brooklyn, a neighborhood dominated by the Bonanno Family. Gallo moved residences during this decade but remained in Bushwick, where he was a close neighbor of future Bonanno capodecina Frank Tartamella, the nephew of Family consigliere John Tartamella.

Ciro Gallo married Caterina Argento, born in Alcamo, Trapani, a comune immediately neighboring Castellammare del Golfo. Castellammare was the hometown of John Tartamella along with much of the Bonanno leadership, including Joe Bonanno himself. The Bonanno Family unsurprisingly had historic members from Alcamo and genealogical records show occasional interrelation between mafiosi from the two towns. Today the Sicilian Families in Castellammare and Alcamo belong to the same mandamento (mafia district) despite an on-and-off rivalry within Cosa Nostra that occasionally results in one gaining power over the other.

Gallo and Argento’s 1933 marriage took place in Marlboro, a tiny Upstate New York town on the Hudson River later noted for a small Sicilian colony from Agrigento that maintained strong connections to the New Jersey DeCavalcante Family. This colony included immigrants from Ribera and Alessandria della Rocca, both villages whose compaesani (townsmen) network factored heavily into the DeCavalcante Family’s membership in New York and New Jersey. The Western Agrigento towns that produced DeCavalcante members are relatively close to Ciro Gallo’s hometown of Palazzo Adriano and numerous comuni in this interprovincial region led immigrants to the same areas of the United States, many of which have known mafia links even in “out of the way” locations.

The DeCavalcante Family eventually had several inducted members who maintained a residence in remote Marlboro and boss Sam Rizzo DeCavalcante referenced multiple Marlboro-based members on FBI recordings during the 1960s. By then his Family had gambling operations in the area and when future capodecina Anthony Rotondo cooperated decades later he testified that member-owned properties in this area could be utilized to dispose of mafia murder victims though it’s unclear if these grim deeds ever took place. Following the mass-incarceration and defection of high-ranking DeCavalcante members like Rotondo in the early 2000s, the Family would be guided by underboss Joe Miranda, a resident of Marlboro who maintained a legitimate business in New York City, though Miranda’s heritage came at least partially from Partinico, near Alcamo, rather than the Palermo-Agrigento border.

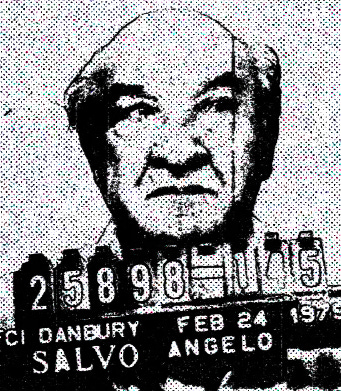

Longtime Bonanno leader Angelo Caruso also spent time in Marlboro, NY. Caruso was Sicilian but an outlier in the Bonanno Family in that he came from Enna province rather than Northwest Sicily. Angelo Caruso was familiar with the DeCavalcantes, noted for being one of capodecina Frank Rizzo DeCavalcante’s closest friends. For this reason it was Caruso who Frank’s son Sam sought out when the “Banana War” crisis broke out in 1964. Caruso was on the Family’s ruling panel at the time and once temporarily served as underboss and acting boss in the early 1930s, being described in Joe Bonanno’s autobiography as the representative of a non-Castellammarese faction in their Trapani-centric Family after the murder of Salvatore Maranzano in 1931.

The Rizzo DeCavalcantes were like Caruso and Ciro Gallo in that they were not part of the dominant compaesani group within their mafia Family, with Frank and Sam tracing their heritage to metropolitan Palermo rather than Agrigento. The Bonanno Family had its own members from Agrigento and Angelo Caruso intermarried with the captain of one of these groups in New Jersey, perhaps providing a connection to the DeCavalcante-linked Agrigento colony in Marlboro when he visited. There were other, closer mafia connections that may have brought Caruso and Gallo to the Marlboro area, too.

Even marriage in an innocuous Upstate New York hideaway was not without significance in the Cosa Nostra network, where social plans and vacations were guided by the mafia subculture, just as crime and other subversive activity followed the same currents. Whether this played a direct role in Ciro Gallo choosing Marlboro as his choice of venue for marriage will be discussed more later in this article but like other early American mafiosi from Sicily his known traveling patterns are almost exclusively tied to mafia colonies.

Stepping back to Ciro Gallo’s initial arrival in the United States via Tijuana, the decision to enter the country through California was not random. Gallo’s brother Geraldo Gallo, known as “Joe”, was living in Los Angeles and there was a Cosa Nostra Family based in Southern California with a faction in San Diego. San Diego-based members like Frank Bompensiero would regularly visit Tijuana and a group of deported members took up residence there for a time, associating closely with the Southern California membership.

Hidden behind more infamous New York figures with the same name, Ciro’s brother Joe Gallo was identified by later Bay Area informants as a Cosa Nostra member himself, belonging to the San Jose Family. There is no evidence of Joe Gallo’s involvement with the Los Angeles Family during his residence there in the 1920s, though his brother Ciro’s decision to enter the country through Southern California was no doubt connected to Joe’s presence in the state. Like Ciro, Joe Gallo’s known movements are linked to areas with a mafia presence.

The Gallo brothers’ hometown of Palazzo Adriano has its own Cosa Nostra Family, acknowledged by Italian investigators as recently as 2014. A handful of members were arrested along with the Family boss, who shared his surname with the sitting mayor. This investigaton revealed a leading member of the local Family who engaged in extortion was a municipal employee in Corleone, which sits in the same general area of Palermo province.

Palazzo Adriano has long been in the shadow of nearby Corleone and other inland Palermo villages, though Palazzo Adriano is itself a distinct Family in the Corleone mandamento, a regional mafia district comprised of individual village-based Families that report to a more dominant representative in the area, in this case Corleone. All of the Families in a mandamento retain their autonomy as individual organizations while falling under the influence of the capomandamento, a title separate from Family rappresentante. Though the Palazzo Adriano organization is politically and geographically intertwined with Corleone, few links can be found between early Palazzese mafiosi in the United States and the influential Corleone network that informed the development of American Cosa Nostra groups.

Palazzo Adriano was formed by Arbëreshë settlers, ethnic Albanians who adapted to Sicilian culture but nonetheless preserved a unique identity. One of the earliest known bosses of the New York Bonanno Family, Nicolo Schiro, was born in nearby Roccamena and had Arbëreshë roots in his bloodline. This was not a barrier to mafia membership nor did it prevent a member from reaching the highest levels of leadership, as evidenced by Schiro. Nicolo Schiro’s grandfather was also the mayor of Roccamena in the 1840s and the comune’s Cosa Nostra Family belongs to the Corleone mandamento alongside Palazzo Adriano.

Nicolo Schiro’s heritage was the result of cross-pollination between Roccamena and Camporeale, the latter part of Trapani province at the time and Schiro lived in Camporeale prior to entering the United States. He was also an alleged relative of an even earlier Bonanno boss, the Camporealese Paolo Orlando. It is unknown if Ciro Gallo shared Nicolo Schiro’s Albanian blood, though there is a certain probability given his birth in the heavily Arbëreshë colony of Palazzo Adriano. If nothing else the two men shared affiliation in the Bonanno Family.

Joe Gallo’s residence in Los Angeles when brother Ciro arrived in 1927 plays into possible Arbëreshë roots as well. Early members of the Los Angeles Family came to the United States from Piana dei Greci, today known as Piana degli Albanesi for its history as a core Albanian settlement and the village’s mafia transplants in California had Arbëreshë bloodlines. The Gallo brothers’ heritage in Palazzo Adriano made Los Angeles a natural fit if indeed they were tapped into the local Cosa Nostra environment dominated by natives of Piana dei Greci. The two villages don’t directly border one another, with Corleone and other comuni resting between them, but Sicilian Arbëreshë colonies were closely connected through shared Albanian heritage.

Ciro Gallo could have been recognized as a Sicilian mafia member prior to entering the United States. Formal transfers from Sicilian Families to United States groups were common during this era, with Gambino member Nicola Gentile’s memoirs showing the ease and fluidity of these shifting arrangements. Though transfers were fluid, they were still highly formal. The leadership of each Family had to approve the process and a letter was exchanged to officially confirm the change in affiliation. When Gentile transferred to the San Francisco group he described how the Family consiglio was involved, a reference to a governing council distinct from the administration in early American as well as Sicilian Cosa Nostra Families.

A member did not have to transfer in every case, though establishing permanent residence in the area of a local Family generally facilitated the process. Later sources stated that transfers between Sicily and the United States became much less common, with some Families discouraging international transfers though they still occurred on occasion. Localized relationships in the United States led to more organic recruitment processes based on proximity rather than Sicilian credentials and Cosa Nostra in many locations became pan-Italian.

There are examples of the heavily Sicilian DeCavalcante and Bonanno Families continuing this international transfer process even into more modern years. A recent investigation showed that the Gambino Family, which today is run by a faction with Sicilian mafia roots, also arranged the transfer of a Sicilian member from Montelepre within the last ten years. The member was required to produce a letter from his Sicilian boss just as members like Nicola Gentile were required to do a century earlier.

Before the 1930s this transfer process was incredibly commonplace, with Nicola Gentile describing his smooth transfer between Families in the United States and Sicily, then back again. Gentile followed the required protocol in each instance. During a return from Sicily to New York City in the early 1920s, Nicola Gentile was expected to transfer to the Gambino Family but to avoid being assigned a murder contract from boss Salvatore D’Aquila he made arrangements with his friend Nicolo Schiro to transfer into the Bonanno Family for a brief period.

My suspicion that Ciro’s membership predated his arrival to the United States comes from his age upon entering the country and the quickness with which he established himself in important mafia circles despite having moved across the country from California to New York as a fresh immigrant from Sicily. Though inducting middle-aged and even elderly recruits has become commonplace in US organizations during recent decades, the early Sicilian and American mafia actively recruited teenagers and young men. San Jose member and FBI informant Frank Sorce reported a rule that American groups could induct members who were 17-years-old, while the Sicilian branch would induct members as young as 13. Harry Riccobene of Philadelphia was inducted at age 16, just shy of his 17th birthday — Harry Riccobene’s induction took place in 1927, the same year Ciro Gallo entered the country.

Palermo pentito Tommaso Buscetta, too, was inducted into Cosa Nostra as a teenager in the 1940s and other pentiti have given similar descriptions of the Sicilian mafia favoring the induction of younger men. At age 29, Ciro Gallo had been eligible for membership in Sicily for 16 years according to the guidelines described by Frank Sorce and events to come show Gallo was accepted among national mafia leaders several years after arriving to the United States without having spent a significant amount of time in their midst. It cannot be confirmed if Gallo was already a member of Cosa Nostra in Sicily when he arrived but he was evidently well-connected.

The Bonanno Family & Palazzo Adriano

The majority of early Bonanno members were the product of Trapanese mafia clans who maintained their tradition in the original Sicilian style. Compared to their peer organizations in New York City, the Bonannos were among the most reluctant groups to recruit through purely local relationships during earlier stages of the American mafia’s evolution, with the late 1940s and 1950s serving as the first period where the Bonannos brought in non-Sicilian and otherwise Americanized members in significant numbers. Even then, they stayed close to their clan roots when it came to Family administration.

Ciro Gallo’s 1930 residence in Bushwick and marriage to an Alcamese woman could have paved the way for his transfer or induction into the Bonanno Family, and it was certainly no detriment to this endeavor, but deeper investigation shows his relationship to the Bonanno Family was not necessarily limited to these two factors alone. Though Gallo's hometown of Palazzo Adriano in Palermo province is not common in Bonanno Family history, Bonanno member Tony Canzoneri's heritage was from there as well.

Tony Canzoneri was only recently confirmed as a Bonanno member through FBI files and a reference made in one of Bill Bonanno’s books, though his father Joe Bonanno did describe a relationship with the Canzoneris earlier in his own autobiography. Prior to this, Canzoneri was well-known as one of the most successful professional boxers of his era, having held world titles five separate times and securing a well-earned place in the Boxing Hall of Fame. Bill Bonanno not only identified Canzoneri as a made member of the same mafia organization Bill himself belonged to, but also a capodecina under Joe Bonanno’s leadership. Bill Bonanno’s book included a photo of his father Joe standing proudly, arm-in-arm with Tony Canzoneri.

Bill Bonanno’s claim initially puzzled some readers who questioned how or why such a successful fighter would participate in Cosa Nostra. However, a significant number of amateur and professional boxers became mafia members and associates, including well-known names like Vincent “Chin” Gigante. Louis Salica, a second-generation Palermitano member of the Gambino Family, was another boxing champion like Canzoneri before his entry into the mafia. Some of these boxers-turned-mafiosi achieved little to no success in boxing, but Tony Canzoneri was not fundamentally different from them in approach — he was just really good at boxing and they weren’t. The number of Cosa Nostra figures involved in boxing during their formative years makes it a matter of probability that some of them would be noteworthy.

Born in Louisiana in 1908, Tony Canzoneri and his family would remain in the South through at least 1913. New Orleans was the primary port for Italian immigrants until 1898, at which time the entry point for most Sicilians shifted to New York’s Ellis Island. This change was reflected in the politics of Cosa Nostra, with the epicenter of the American mafia shifting to New York City and New Orleans becoming less significant in the organization’s national politics. The Canzoneris did not immediately move to New York from Louisiana, however.

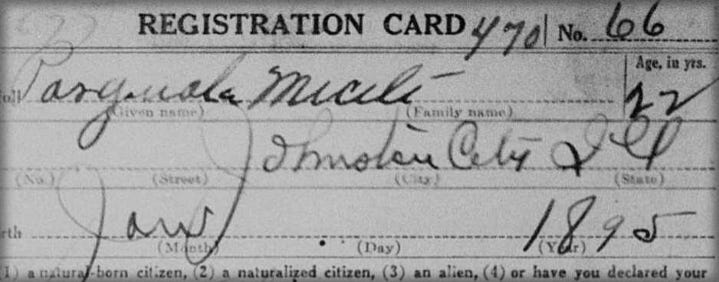

By 1920 the Canzoneris were living in Johnston City, Illinois, in the far southern part of the state. Chicago was a significant distance away but also had a colony of immigrants from the Canzoneris’ hometown of Palazzo Adriano and several Chicago mafia figures would trace their heritage there. They factor into this story, though it will be later. Johnston City, where the Canzoneris lived, was in Williamson County closer to St. Louis, MO, which had its own immigrants from Palazzo Adriano involved with mafia activity. Future St. Louis rappresentante Pasquale Miceli was from Burgio in Agrigento province, a comune near Palazzo Adriano, and was himself residing in Johnston City circa 1917-1918 prior to living in Chicago and eventually St. Louis.

An earlier St. Louis mafia leader was Domenico Giambrone, a native of Palazzo Adriano who arrived in 1903 to his father in Birmingham, where there was a short-lived Alabama Family formed around a Western Sicilian colony from the interprovincial area between Palermo and Agrigento. Giambrone’s stay in Birmingham was temporary, as he soon settled in St. Louis, a location that may have had a Family long before the turn of the century. The Canzoneris lived in outlying Johnston City during the general period Domenico Giambrone was active in criminal activity in St. Louis, though there is no evidence the Canzoneris knew him or had a presence of their own in Missouri beyond living nearby in Southern Illinois. Tony Canzoneri’s future membership in the Bonanno Family suggests they were at least familiar with the mafia subculture and it’s likely they knew of fellow Palazzese immigrants across the state line in St. Louis.

Illinois had a mafia presence throughout much of the state during the era the Canzoneris lived there. In addition to Chicago, there were other distinct, formally-recognized Illinois Families in Chicago Heights, Springfield, Rockford, and even an adjacent group in Gary, Indiana, with the Missouri Families in Kansas City and St. Louis falling into similar mafia networks. Some of these organizations had a presence in rural areas near their central jurisdiction though it has yet to be confirmed what, if any, Cosa Nostra presence existed in Williamson County beyond the temporary residents mentioned here. The Canzoneris would leave Illinois in subsequent years and their compaesano Domenico Giambrone was violently murdered in St. Louis in 1934. By that time the Canzoneris were nowhere near Missouri or Illinois.

Domenico aside, the Canzoneris did have ties to the Giambrone surname: a maternal first cousin of Tony Canzoneri married a Frank Giambrone. This Giambrone was born in Louisiana to parents from Palazzo Adriano like the Canzoneri children and this branch of Giambrones moved to New York alongside the Canzoneris. The interrelated Canzoneris and Giambrones would remain in close proximity for the remainder of their lives.

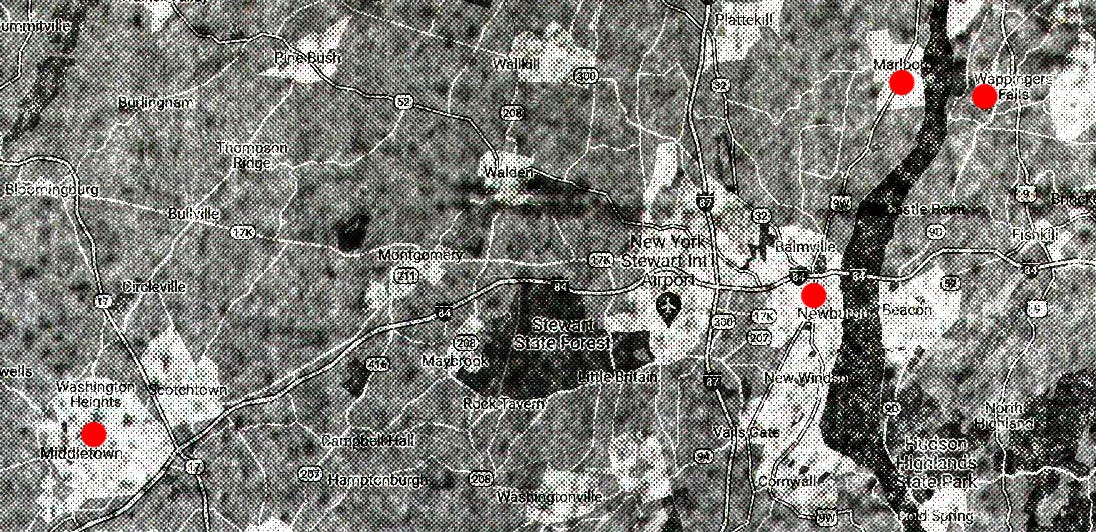

After a stay in Brooklyn beginning in 1923 or 1924, where Tony’s father Giorgio Canzoneri established a grocery store, Tony’s parents and siblings would move to the Marlboro area by 1930 where they were joined by the Giambrones near the town of Newburgh directly on the Hudson River. Tony himself had interests in Newburgh, taking ownership of a hotel in the area after his boxing career ended. Joe Bonanno describes in his memoir how the baptism party for his son Joe Jr. was held at the Newburgh Canzoneri Hotel.

Bonanno Family leaders had a long history in the same general area where the Canzoneris settled in Upstate New York. Joe Bonanno and his uncle Giovanni Bonventre ran a dairy farm in Middletown and members of the Bonanno Family often visited, as evidenced by photos and stories in the Bonanno father and son’s memoirs. Like Canzoneri, Giovanni Bonventre was a capodecina in the Family and Bonanno says it was Bonventre who managed the Middletown farm. Joe Bonanno’s predecessor Salvatore Maranzano infamously owned property in nearby Wappingers Falls, a short distance up the Hudson River on the opposite bank from Newburgh. Maranzano held high-level meetings and induction ceremonies on his Wappingers Falls estate in addition to running stills and bootlegging operations in the area with the help of Bonanno Family affiliates.

Significantly, Wappingers Falls is directly across the river from Marlboro, NY, which sits on the same side of the Hudson as Newburgh. Joe Bonanno’s autobiography even includes a photo of himself in Marlboro. Though Ciro Gallo’s name is far more obscure than the Family leaders mentioned here, his 1933 marriage in Marlboro is just one of many connections the Bonanno group had to this area up the Hudson River.

That Ciro Gallo married in a town close to Newburgh, where his Palazzo Adriano compaesani the Canzoneris had a presence, is yet another connection point in this emerging picture. This image is made more clear by records for Tony Canzoneri’s father Giorgio. Tony’s parents and siblings were living in the area circa 1930 and Giorgio died there in 1946, being buried in Newburgh. The Canzoneris were surrounded by Italian neighbors, another sign the Hudson River area was an attractive colony.

As evidenced by the DeCavalcante presence there, Marlboro not only drew Italians but specifically groups of tightknit Western Sicilians. In addition to the Canzoneris, the towns of Marlboro and Newburgh had other residents from their hometown, including families with the name Schiro, and the Canzoneris’ next door neighbor was an elderly man named Calogero LoBurgio who came from Palazzo Adriano like them. LoBurgio was also the maiden name of Ciro Gallo’s mother.

A man matching Calogero LoBurgio’s name and year of birth in Trinidad, Colorado, married a woman named “Masarachia” in 1906. The man living next to the Canzoneris in Marlboro was listed as widowed, so without a death record for the Colorado man’s wife there is no way to confirm it’s the same man beyond his identical name and age but it appears likely. The Masaracchia surname is most commonly found in Palazzo Adriano and the LoBurgio in New York State can’t be placed elsewhere at the time using available records. This is a stronger indication the man in Colorado is the same Calogero LoBurgio given his name, age, and hometown appear to be identical to the man living next to the Canzoneris in later years. His wife’s surname of Masaracchia even surfaces in modern Palazzo Adriano mafia circles.

The current mayor of Palazzo Adriano is named Salvatore Masaracchia and Pietro Paolo Masaracchia has been identified as a recent Cosa Nostra boss within the comune. The surname apparently lends itself to important positions, be it in municipal government or the mafia, though there may be crossover given another current Palazzo Adriano mafia member was employed with the municipality of Corleone. Cosa Nostra leadership in Sicilian villages often draws from multi-generational membership, so Pietro Paolo’s position as rappresentante could indicate the Masaracchia name goes back further in the local Family.

Another current member of the Palazzo Adriano Family arrested with Pietro Paolo Masaracchia in 2014 is Nicola Parrino. Three Pennsylvania-based Parrinos from Palazzo Adriano were identified by the FBI as made members of the historic Pittston Family: Frank, John, and Angelo Parrino. Angelo would marry into the Pittston leadership, who came from Caltanissetta province. They are not listed next to one another, but when the Parrinos came to the United States a man on the same page of the ship manifest was from Alcamo in Trapani, the hometown of Ciro Gallo’s wife.

The Parrinos’ membership in Pittston again places Palazzo Adriano in proximity with the Bonanno Family network through the Pittston Family’s Castellammarese faction in New York’s Southern Tier. Not only were the Parrinos members of the same organization as the Southern Tier group, the son of senior member Stefano LaTorre, from Montedoro in Caltanissetta, told the FBI how LaTorre’s son-in-law Angelo and John Parrino once sat on a Family council with the Castellammarese Joe Barbara where they presided over an underworld trial that decided his father’s fate. Connections between Palazzo Adriano and Bonanno-connected villages in Trapani are a trend that runs throughout this article.

The Parrino name connects directly to the Canzoneris, as Tony’s father Giorgio Canzoneri arrived to an uncle named Parrino when he came to the United States and further exploration will show other connections between the Canzoneri and Parrino surnames later in this article. Beyond speculative connections between the Canzoneris and Pittston, the Canzoneri-connected Calogero LoBurgio’s marriage in Trinidad adds Colorado as another geographic marker among this well-traveled set of names and at least one Palazzese mafioso in the Chicago area also spent time there. Trinidad was not without its own place in the Cosa Nostra network, being the residence of leading Colorado Family members who had close ties to the Bonanno Family. Trinidad wasn’t far from Pueblo where the Colorado Family likely formed.

Colorado & Marlboro

Early Pueblo rappresentante Pellegrino Scaglia was murdered in 1922 and Nicola Gentile described how national meetings were held to resolve the matter. Scaglia was from Burgio, Agrigento, and his wife came from Palazzo Adriano which sits near Burgio just across the provincial border in Palermo. This is further indication of a Palazzese colony in Southern Colorado and of course an additional mafia tie-in. It also draws back to St. Louis boss Pasquale Miceli who was himself a Burgio-born compaesano of Scaglia that lived in Johnston City, Illinois, along with the Palazzese Canzoneris.

Relatives of Pellegrino Scaglia would flee Pueblo following his murder and ended up in both Kansas City and St. Louis, Scaglia himself having hid out in St. Louis on one occasion before his death. His father-in-law Francesco Accomando from Palazzo Adriano was one of the Pueblo members who transferred to Kansas City after an underworld trial was settled in their favor, as were the Chiappetta brothers from Poggioreale in Trapani. Scaglia’s nephew Luca Colletti was yet another, coming from Burgio like him. Palazzo Adriano’s close relationship to Western Agrigento and Southern Trapani are evident among Pellegrino Scaglia’s clan and these villages together informed certain branches of Cosa Nostra.

The Colorado group in Pueblo and Trinidad was dominated by mafiosi from the Agrigento villages of Lucca Sicula and Burgio as well as neighboring Trapani, with interrelation between men from the two provinces that also included Palazzo Adriano in Palermo as evidenced by the Scaglia marriage. The Agrigento towns are close to the same DeCavalcante-linked villages that populated a colony in Marlboro and Angelo Caruso’s brother-in-law Joseph Colletti, a Bonanno capodecina, was from Lucca Sicula which like Burgio shares a regional affinity with Palazzo Adriano. Pellegrino Scaglia’s nephew Luca Colletti, a Pueblo and Kansas City member, was from Burgio as mentioned, showing the surname surfaces there as well as Lucca Sicula. The Bonanno Family’s Joe Colletti lived in Manhattan’s East Village prior to New Jersey and Caruso was a soldier in Colletti’s crew after having stepped down as interim boss in the early 1930s. It would be Angelo Caruso who became Colletti’s eventual succesor as capodecina.

Angelo Salvo from Alessandria della Rocca, Agrigento, would head part of this crew in New Jersey during the late 1970s. He maintained close friendships with the DeCavalcante Family and his nephew Antonino Busciglio was a Bonanno member employed by the DeCavalcante-run Local 394 in Elizabeth. Busciglio was later murdered in 1983 a week after being observed in a heated argument at the home of a DeCavalcante figure from his hometown of Alessandria.

Angelo Salvo connects to Illinois, being born in Williamsville outside of Springfield, where a quiet Family existed. As with Johnston City, which attracted mafia-linked immigrants from Agrigento and Palazzo Adriano like Pasquale Miceli and the Canzoneris, other rural areas of Southern Illinois show links to the Cosa Nostra network and the small Springfield Family included mafiosi from Western Agrigento, including underboss Domenico “Nick” Campo from Montevago. Though he fit in perfectly with the mafia environment in this part of Illinois, Salvo’s family returned to his native Alessandria della Rocca after his birth where he spent his formative years before arriving back in the United States in adulthood, settling in New Jersey. His nephew Antonino Busciglio was reportedly inducted into Cosa Nostra in Sicily before eventually joining his uncle in America.

Angelo Salvo and his nephew have common mafia surnames from Alessandria della Rocca in their immediate family tree and FBI reports state Antonino Busciglio transferred his membership from Sicily to the Bonanno Family in the late 1960s. The books were closed in New York at this time and in some exceptional cases Sicilian members did transfer into local American Families much as they had decades earlier. One report indicates it was Salvo’s friend Angelo Caruso who helped facilitate this process for Sicilian mafiosi, with Caruso described as the point of contact for recent “Italian” immigrants. Despite coming from Leonforte in Enna province, just east of central Sicily, Angelo Caruso maintained a distinguished status even among men from the island’s Western Sicilian mafia strongholds.

The cousin of Caruso’s brother-in-law Joseph Colletti was Vincenzo “Jim” Colletti, a fellow Bonanno member who moved to Pueblo and became the local rappresentante after transferring membership. Jim Colletti was partnered with Joe Bonanno in the Colorado Cheese Company, which was based in Trinidad where the Canzoneri-connected Calogero LoBurgio from Palazzo Adriano was apparently married in 1906. Bonanno may have even served as the Colorado Family’s representative on the Commission for a time, showing how Sicilian chain-migration networks influenced Cosa Nostra politics for years to come.

An FBI report reveals Jim Colletti maintained relations with his cousin’s Bonanno decina in New Jersey, as evidenced by records of a pre-Apalachin 1957 phone call between Colletti and future crew leader Angelo Salvo. The FBI also documented contact between Jim Colletti and Caruso, the other Angelo who would become the crew’s captain shortly thereafter.

Angelo Salvo was surely familiar with Marlboro, just as Angelo Caruso was. DeCavalcante members with property in Marlboro came from Salvo’s hometown of Alessandria della Rocca and his ties to compaesani in the DeCavalcante, Tampa, and Gambino Families were documented by the FBI. Given his one-time capodecina Angelo Caruso hid out in Marlboro during the 1960s “Banana War”, this arrangement could have come via Salvo’s ties to DeCavalcante members in Marlboro in addition to the Bonanno leadership’s ongoing presence in the area. The well-connected Caruso could have utilized any number of relationships to “lam it” along the Hudson River in the 1960s and he was likely among the Bonanno Family members who once visited Salvatore Maranzano’s property across the river in Wappingers Falls in the early 1930s.

The Bonanno and DeCavalcante Families had ties but their networks typically overlap only at the fringes. The DeCavalcantes have a reputation as one of the most insular American Families and research shows them to have little engagement in national mafia politics save for Sam Rizzo DeCavalcante throwing himself into early negotiations during the Bonanno Family war as a result of his deceased father Frank’s close relationship with Angelo Caruso. New Jersey Bonanno member Tony Riela from San Giuseppe Jato was also described in FBI reports as a defacto “consigliere” for the DeCavalcante Family who assisted their administration but could not officially take a leadership role due to his membership in the Bonanno Family. Tony Riela’s name comes up repeatedly in Angelo Salvo’s FBI file and like Jim Colletti in Pueblo, Riela was a business partner of Joe Bonanno.

That the Bonanno and DeCavalcante Families intersect in Marlboro of all locations is strange and fascinating. Ciro Gallo and Tony Canzoneri have no known relationships with DeCavalcante figures but Gallo and Canzoneri’s ties to Marlboro places them between the two networks. The Bonanno Family’s New Jersey decina was unquestionably close to the DeCavalcantes, though, and they too had documented ties to Marlboro and Trinidad.

Tony Canzoneri’s shared heritage with Ciro Gallo in Palazzo Adriano becomes more significant when looking at the Canzoneris’ 1930 US Census record after the family moved to Upstate New York. Not only was their elderly neighbor Calogero LoBurgio from 1940 living with them rather than next to them, but he is included this time as an uncle to Tony’s father Giorgio Canzoneri. Records show this was not simply a social designation, common among Sicilians, but the mother of Giorgio Canzoneri was in fact a LoBurgio, making his uncle LoBurgio a blood relative. Tony Canzoneri’s paternal grandmother and Ciro Gallo’s mother were both LoBurgios from Palazzo Adriano.

Ciro Gallo’s choice of Marlboro for his 1933 marriage has quickly become less of a mystery. In addition to attracting Agrigento natives connected to the DeCavalcante Family, there was a colony from Gallo’s hometown of Palazzo Adriano along the Hudson River connected to two known Bonanno members with roots in Palazzo Adriano, with both Ciro Gallo and Tony Canzoneri having close blood relatives named LoBurgio. It also means a possible common relative of the two men previously lived in Colorado where a later boss was directly tied to the Bonanno crew under Joseph Colletti and Angelo Caruso, the latter having spent time himself in Marlboro. Early boss Pellegrino Scaglia pulled from the same roots, his hometown of Burgio being within walking distance of the Collettis’ heritage in Lucca Sicula and Scaglia’s wife being Palazzese like Gallo and Canzoneri.

Unlike Gallo’s marriage to an Alcamese woman, Tony Canzoneri married outside of his Sicilian heritage. His wife was Jewish, so her connections to other mafia lineages can be easily discounted and their relationship was purely a product of relationships formed in New York. Canzoneri was billed as a Brooklyn resident during the peak of his boxing career though records show he was a resident of Manhattan shortly after his 1939 retirement, living on Central Park West in 1940.

The Bonanno Family is most known for its strong presence in Brooklyn and Queens, but there was a significant faction in Manhattan, particularly the East Village and nearby Little Italy. Angelo Caruso was among the influential members who operated out of Manhattan and his brother-in-law Colletti was a previous resident of the East Village himself. However, by 1957 Canzoneri was identified by the FBI as a resident of Jackson Heights, Queens, this report noting his association with Palermo-born New York boss Tommy Lucchese, an equal of Joe Bonanno.

Canzoneri’s atypical life makes grouping him within the Bonanno Family’s patterns of association difficult. Bill Bonanno doesn’t specify when Canzoneri was inducted into Cosa Nostra and promoted to capodecina, though he notes the Family maintained several captains who did not have members under their supervision, utilizing the position more as an honorary title. This arrangement is not unique to the Bonanno Family nor is it reserved for any one type of member, but Canzoneri may have been a candidate for his position given his relative fame as a world-class boxing champion. Joe and Bill Bonanno’s autobiographies show a tendency to favor their relationships with individuals of a certain social status and this could have influenced Tony Canzoneri’s promotion. Bill’s references to Canzoneri show they were proud of their relationship with him.

Tony Canzoneri’s somewhat unconventional background in Cosa Nostra circles is not unique. Joe Bonanno’s first cousin Dr. Martin Bonventre was identified as a Bonanno member in Bill Bonanno’s last book. Bonventre was not simply a practicing medical doctor, he was Director of Medicine at a Brooklyn hospital and his cousin Stefano Magaddino traveled to New York from Buffalo to receive heart treatment from Dr. Bonventre. Bonventre’s father Pietro and virtually all male relatives were members. His path into the organization came from blood relation.

Other Bonanno members were even more atypical. Arizona member Russell Andaloro was a music teacher and Nick Guastella, who previously worked under Salvatore Maranzano in Wappingers Falls, was a sculptor who transferred membership to San Jose. Another Brooklyn Bonanno member who practiced medicine like Martin Bonventre was Dr. Mario Tagliagambe, whose uncle Silvio was murdered in an early New York mafia war. Tony Canzoneri’s celebrity boxing career is positively fearsome in comparison to some of the hobbies and professions within the Bonanno Family.

There is no information indicating Tony Canzoneri’s father Giorgio Canzoneri was a Cosa Nostra member, though Tony’s entry into the Bonanno organization may have come through blood or an unknown marital relation given he grew up in various parts of the United States outside of New York and did not prove himself through local street crime alone, if at all. The Canzoneris’ documented relation to mafia-connected surnames from their hometown of Palazzo Adriano like Giambrone, Masaracchia, and Parrino lends itself to this tradition.

Interestingly, Tony Canzoneri’s mother’s maiden name was Schiro, like the early Arbëreshë Bonanno Family boss Nicolo Schiro. Both the Canzoneri and Schiro names feature prominently in Palazzo Adriano town history and are connected to the historic upper classes of the small village. Nicolo Schiro was similarly a product of this element in his hometown of Roccamena, being the grandson of a former mayor. Though Ciro Gallo’s Albanian family history is speculative, we can confirm Tony Canzoneri was an Arbëreshë like Nicolo Schiro.

Tony Canzoneri’s mother was born in Palazzo Adriano, an Arbëreshë colony, and as Nicolo Schiro’s own Albanian heritage suggests, the Schiro surname is overwhelmingly Arbëreshë. Nicolo Schiro was from Roccamena but had blood and marital ties to other neighboring towns though it can’t be confirmed if he had relatives in Palazzo Adriano. Arbëreshë blood is well-distributed in this area of Palermo province and some of these villages are known for maintaining Albanian dialect and customs even into modernity. There is evidence the Schiros from Roccamena and Palazzo Adriano both had extended relatives in Prizzi and an ancestor of Tony’s mother was named Nicolo Schiro but he was much older than the Bonanno Family boss and lived in Palazzo Adriano, not Roccamena. Tony Canzoneri and Nicolo Schiro were nonetheless two men with Arbëreshë blood who joined the Bonanno Family which gives their story a certain bond outside of confirmed relation.

The same surnames come up in relation to the Canzoneris and Schiros from Palazzo Adriano and Roccamena, too. A different Giorgio Canzoneri from Palazzo Adriano born the same year as Tony’s father arrived to a cousin, Francesco Governale, on Manhattan’s Chrystie Street. The groundbreaking May 2014 issue of Informer Journal identifies an Antonino Governale as brother-in-law to the first known Bonanno Family boss Paolo Orlando, a relative of Nicolo Schiro. When Schiro arrived back in America from a trip to Sicily in 1902, he listed Antonino Governale as his uncle.

This “other” Giorgio Canzoneri, not Tony’s father, shows other potential connections to mafia names beyond Governale. His wife was Antonia Parrino, an Arbëreshë-connected surname shared with a current Palazzo Adriano mafia member and three Palazzese brothers in the Pittston Family referenced earlier. Though this Giorgio Canzoneri’s wife lists her residence as Palazzo Adriano like him and the Parrino name is common there, the Parrino surname is also common in Alcamo, the hometown of Ciro Gallo’s wife. Two murdered brothers from Alcamo had the surname Parrino and were involved with the Bonanno Family.

Rosario Parrino was an Alcamese mafioso who moved to Detroit, where he was killed in 1930 with Castellammarese Detroit boss Gaspare Milazzo. Milazzo was previously a resident of New York and he was deeply connected to top Bonanno Family leaders at the time, if not one himself. Parrino’s older brother Giuseppe remained in New York and was selected by capo dei capi Joe Masseria to replace Nicolo Schiro as Bonanno Family rappresentante. Giuseppe Parrino was killed in 1931 by pro-Maranzano forces who rejected his collaboration with their enemy Masseria in the build-up to the Castellammarese War.

Another trip from Sicily shows the “other” Giorgio Canzoneri traveling with a man from Alcamo and a family from Castellammare del Golfo. They are grouped together on the manifest and the Castellammarese travelers arrived to a Vito Buccellato in New York, a surname inseparable from Castellammarese mafia bloodlines in Sicily, New York City, and Detroit. This Canzoneri’s connection to these Trapanese travel partners could be explained by his wife’s Alcamo-linked surname, though she is likely a product of Palazzo Adriano like other Parrinos related to the Canzoneris.

Though this Giorgio Canzoneri’s age and hometown are a perfect match for Tony Canzoneri’s father, the names and ages of his wife and children differ. Sicilian naming customs could indicate this Giorgio is a first cousin of Tony’s father, as cousins of the same generation are named for grandparents and thus mirror each other in name and relative age. In this case the age is more or less exact and both Giorgio Canzoneris descended from the same small village of Palazzo Adriano where a degree of relation was almost guaranteed among many inhabitants.

Adding to this is Tony’s father Giorgio Canzoneri’s 1903 immigration, arriving to an uncle named Giuseppe Parrino in Louisiana. Both “branches” of the Giorgio Canzoneri name have ties to the same Palazzese surnames, with other threads directly and indirectly linking them to individuals from Trapani. The Canzoneris’ compaesano Ciro Gallo was also from Palazzo Adriano and he married an Alcamese woman in the Marlboro area, where the Canzoneris lived with a biological uncle who shared Gallo’s mother’s surname. This research is circular and though I can’t find the single thread connecting these individuals into one family tree, there is little question as to whether these people knew of one another.

Ciro Gallo and Tony Canzoneri’s exact connection can’t be clarified with the resources currently available, but all of the pieces must be examined before attempting to assemble the puzzle. The nature of mafia research requires acceptance that the puzzle will never be fully complete, though time and dedication reveal many of the pieces do fit together. Ciro Gallo, Tony Canzoneri, and various Palazzese mafia surnames line up better than expected when I first noticed Gallo and Canzoneri shared a Sicilian hometown and though neither man’s background readily matches our understanding of historic Bonanno membership these individuals have opened up new areas of investigation worthy of pursuit.

If there was any remaining doubt about Bill Bonanno’s claim that Tony Canzoneri belonged to the Bonanno Family, further support is found in an early 1970s FBI report listing Anthony “Cannzoneri” [sic] as a deceased Bonanno member. Tony Canzoneri died of natural causes in 1959 but this is the earliest known reference confirming his membership. It’s common for FBI informants to provide historic information about the organization years after the fact, especially member identifications. This information could have come from a contemporary 1970s informant given the timing of the report but it nonetheless shows awareness of Tony Canzoneri’s formal affiliation with the Bonanno Family beyond Bill Bonanno’s published account of Canzoneri as a Family capodecina.

Another Gallo in the Bonanno Family

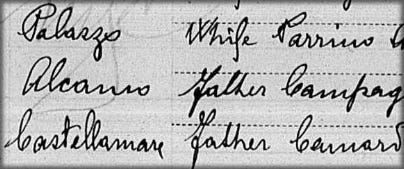

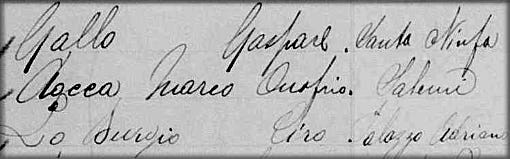

My initial interest in Ciro Gallo came from his shared surname with Baldassare “Benny” Gallo, an early Williamsburg figure suspected of being a leading Bonanno Family member before his 1930 murder. Williamsburg neighbored Ciro Gallo’s residence in Bushwick, with Ciro living near the border of the two neighborhoods. Benny Gallo was not from Palazzo Adriano like Ciro Gallo, his parents instead coming from the inland Trapani villages of Santa Ninfa and Salemi.

These Trapani towns produced a well-hidden but nonetheless influential faction of early members somewhat distinct from the leading Bonanno clans of Castellammare and Camporeale. In addition to Benny Gallo, another early leader among this element was Gaspare Messina, who came from Salemi. Messina was a Bonanno affiliate before moving to Boston where he quickly became the local boss. Messina would temporarily serve as capo dei capi after Joe Masseria was deposed and ultimately murdered in 1931, living again in New York City during this period where he associated with Bonanno leaders while possibly retaining his rank as remote Boston rappresentante.

Bonanno membership from inland Trapani has nonetheless persisted, with 1960s Bonanno boss Paul Sciacca coming from Salemi and recent Bonanno captains Vito Grimaldi and his son Joe tracing their heritage to Santa Ninfa. Vito Grimaldi’s father Giuseppe was identified as an earlier Bonanno capodecina like his son and grandson. Famed mafia journalist Jerry Capeci identified the elderly Vito Grimaldi as an advisor to the Bonanno “Sicilian faction” within the last decade though he was an American native born in New York.

The Grimaldis were one of several families from Santa Ninfa in the Bonanno Family, with one-time acting capodecina Joe DiMaria also descending from this village and interrelating with the historic leadership’s hometown of Camporeale, where half of Nicolo Schiro’s parentage descended. Several younger men connected to inland Trapani have been identified as holding the positions of captain and acting captain in recent years, though they don’t have surnames common to this discussion. At least one of these men traces his heritage to Partanna, where the Bonanno Family Restivos came from. Louis Restivo and his father Biagio both served as captains like all three Grimaldis and the men were intimate associates over multiple generations.

As with the Restivos, these younger men with ranking positions are also connected to the Grimaldis and operate in the same parts of Queens. One of them is the son of a heroin trafficker from the 1980s who was identified as a Sicilian mafia figure. His surname is heavily associated with mafiosi in the town of Gibellina, which sits beside Santa Ninfa, Salemi, and Partanna. These patterns reflect an overlooked element buried deep in Bonanno Family history and somehow remain relevant, with former Castellammarese Bonanno associate Francesco Fiordilino being aware himself of men from these hometowns. Fiordilino’s older relatives were important members in the Bonanno Family as well as Castellammare but he was “on record” with Vito Grimaldi for a time and knew Grimaldi to maintain ties to his ancestral hometown of Santa Ninfa, where his wife was born.

Paul Sciacca’s name is well-known but his heritage is rarely referenced in coverage of the Bonanno Family. Sciacca was from Salemi and married a woman from Santa Ninfa, showing overlap between the same towns evidenced earlier in Benny Gallo’s family tree. This faction of the Bonanno Family eventually migrated from Williamsburg and Bushwick to nearby neighborhoods in Queens and later Long Island while continuing to serve a vital role in organizational politics. Paul Sciacca himself would serve as Family boss in the wake of the 1960s “Banana War” but his leadership was marked by instability due to fallout from the conflict.

Ciro Gallo was active in Bushwick, which was near-inseparable from Williamsburg in context of Bonanno activity, but Ciro’s 1927 arrival in California and Benny Gallo’s 1930 murder would have left little time for the two men to associate after Ciro moved to Brooklyn. Benny Gallo has not been definitively identified as a Bonanno member but his Trapani birth, residence in Williamsburg, and documented stature in local rackets make him a possible Family leader during the 1920s. Researchers should not make the mistake of correlating publicity and outward appearances with formal rank or even membership, as the inner-workings of the organization don’t always reflect what’s visible to outsiders, but it can often be inferred when looking at a figure’s Sicilian hometown and perceived stature in early Cosa Nostra.

New York mafia historians Angelo Santino and Richard Warner agree Benny Gallo was likely an influential Bonanno member in Williamsburg based on his reputation and the patterns outlined throughout this section. Ostensibly the manager of a Brooklyn restaurant, the Secret Service was well-aware of Benny’s counterfeiting activities and a corresponding 1922 arrest noted several associates whose ancestry can be traced to Salemi, where Gallo was living prior to New York City. That Benny Gallo had heritage in Santa Ninfa and Salemi and associated with men from this part of Trapani in Williamsburg suggests he was a spiritual predecessor of men like the Grimaldis and Restivos as well as Paul Sciacca and Joe DiMaria. He may have been a successor to Gaspare Messina after the Boston rappresentante first left New York.

Benny Gallo’s 1930 murder is not mentioned by Joe or Bill Bonanno and the exact motivation for the killing is unknown, with journalists of the time forced to speculate. Law enforcement and the media alike often erroneously attributed early “gangland” murders to racket-based motivations when later cooperation by mafia insiders reveals these murders to be the product of internal Cosa Nostra politics. Benny Gallo’s murder might never be properly contextualized but I’m more likely to assume his killing was political given other events in the Bonanno Family at the time. Several Bonanno leaders were murdered between 1930 and 1931 prior to and during the Castellammarese War.

An examination of immigration records does open up a potential connection between Ciro Gallo and Benny Gallo. Benny's father Gaspare Gallo came to the US from Santa Ninfa in 1904 with a man from Salemi and listed immediately after them on the manifest is a Ciro LoBurgio from Palazzo Adriano, the latter headed to Chicago. Ciro Gallo’s mother was a LoBurgio from Palazzo Adriano and his brother Joe Gallo, the San Jose member, initially headed to relatives in Chicago upon arrival in America. As established earlier, the LoBurgio surname is a common link between Palazzese Bonanno members Ciro Gallo and Tony Canzoneri.

Tony Canzoneri’s family moved to Brooklyn when Benny Gallo was a powerful figure in Williamsburg and though Tony’s relatives moved to the Newburgh area soon thereafter, Tony was still billed from Brooklyn as his boxing career played out. It’s striking that Benny Gallo’s father was from Trapani but came to the United States with someone whose surname and hometown have direct ties to fellow Bonanno members Ciro Gallo and Tony Canzoneri.

It's interesting too this LoBurgio shares a first name with Ciro Gallo, as given names are generally derived from relatives. This LoBurgio was around a decade older than Ciro Gallo and would make two return trips to Sicily. He returned to the United States in 1914, heading to St. Louis where his compaesano Domenico Giambrone was a leading mafioso, then returned to Sicily again. Ciro LoBurgio’s arrival in 1921 listed his destination as Kingston, Illinois, a small town neighboring Johnston City where young Tony Canzoneri and his family were living at the time, their blood ties to the LoBurgio name already established.

I couldn’t confirm the relationship between Benny’s father Gaspare Gallo from Santa Ninfa and his fellow traveler Ciro LoBurgio from Palazzo Adriano, neither could I confirm Ciro LoBurgio is a direct relative of compaesani like Ciro Gallo’s mother or Tony Canzoneri’s great-uncle and grandmother who share the LoBurgio surname. Ciro LoBurgio’s presence in Chicago and Southern Illinois like Joe Gallo and the Canzoneris, respectively, place them in the same colonies at the very least. As will be evidenced later, Ciro Gallo was directly connected to Nick DeJohn, a Chicago member with Palazzo Adriano heritage, and an older Palazzese mafioso related to DeJohn, Sam DiGiovanni, spent time in Colorado before residing in the Chicago area himself.

Researching mysterious Cosa Nostra figures does produce occasional coincidences. Sometimes a name, location, or seemingly obvious connection turns out to be a red herring. More common in my experience, though, is that these coincidences end up being part of the complex and confusing web of relationships that form the mafia network. Stated clearly, Benny Gallo’s father came to the US with a man from Ciro Gallo’s hometown who shared his mother’s surname. This man went to Chicago where Ciro’s brother would arrive a decade later and he then went to Southern Illinois while Tony Canzoneri lived there. Ciro Gallo and Tony Canzoneri in turn ended up in Brooklyn where Benny Gallo operated and they joined the same Cosa Nostra Family. Ciro LoBurgio provides a potential link between all three Bonanno members.

We know of multiple connections between Palazzo Adriano and Bonanno-connected Trapani towns. The Chicago member from Palazzo Adriano with a confirmed relationship to his paesani Ciro and Joe Gallo, Nick DeJohn, was also said to be related to local Chicago mafioso Vincenzo Benevento from Partanna, near Benny Gallo’s hometown of Santa Ninfa. In Brooklyn, Chicago, Pittston, Colorado, California, and Sicily we see people from Palazzo Adriano and different parts of Trapani end up in close proximity with one another.

Sicily is a small island and though relations are often formed along relatively rigid compaesani lines, mafia networks were established throughout the island and many of these towns are not a great distance from each other on a map. Cross-pollination between Sicilian villages shows up in other mafia bloodlines and mafia historian Angelo Santino has often reminded me, “You can fit Sicily inside the state of Massachusetts.” Santino used to live in Trapani. As guarded and insular as the mafia is, it seeks to expand its ties within the subculture, connecting to other Sicilian villages and even parts of mainland Italy. It occasionally retracts these connections, too, often through violence. This is true for American Cosa Nostra networks as well.

The John Bazzano Murder & National Politics

Ciro Gallo’s ancestral links to Cosa Nostra figures are based on curious circumstantial connections, but concrete evidence linking Gallo to high-ranking mafia figures and their corresponding politics surfaced a short time after he established residence in Brooklyn. This was punctuated by a violent murder that has been well-documented but its alleged participants have not been properly dissected.

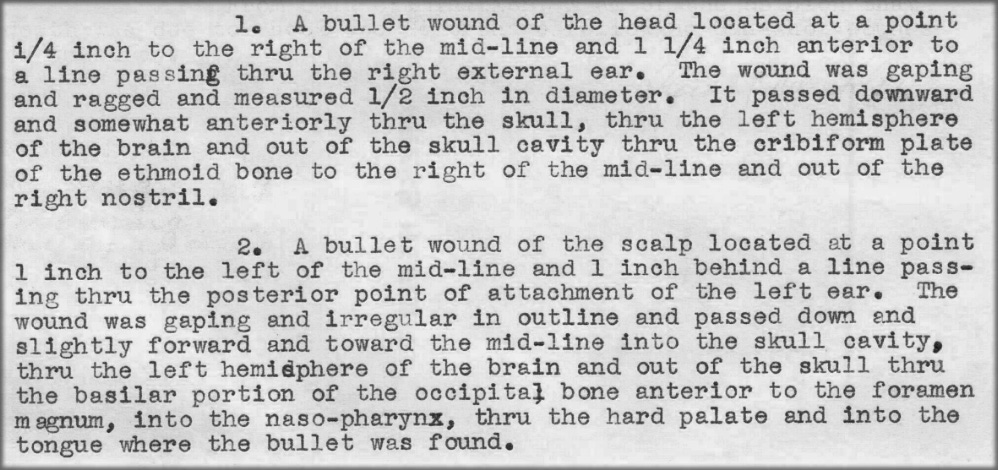

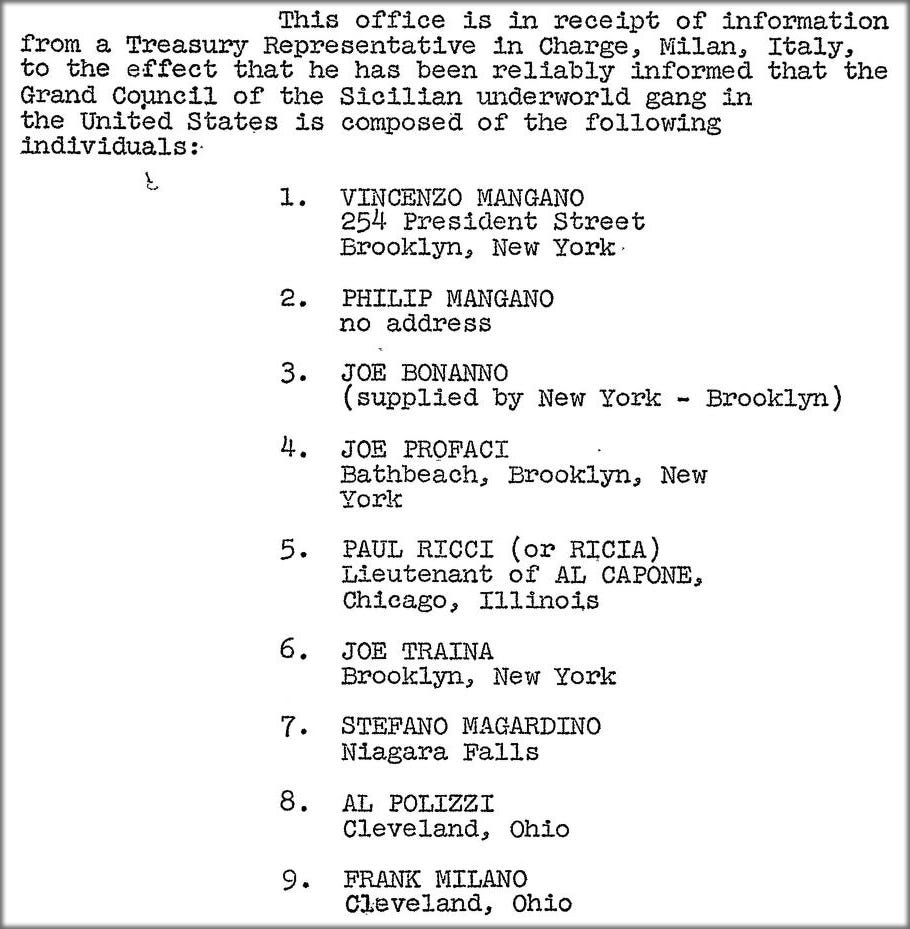

In 1932, Ciro Gallo was arrested in New York City as a suspect in the disappearance and murder of Pittsburgh boss John Bazzano, whose mutilated body was discovered in a bag on the streets of Brooklyn. Among those arrested with Gallo were Colombo Family members John Oddo and Tony Bonasera, Gambino capodecina Giuseppe Traina, Buffalo members Paolo Palmeri and Sam DiCarlo, as well as Pittston boss Santo Volpe, “Peter Lombardi” of Trenton, and Pittsburgh figures Charles Spallino, Michael Russo, Michael Bua, and Frank Adragna. Pittston Family member Angelo Polizzi was also arrested, as was the infamous Albert Anastasia of Brooklyn. These men were detained by police at a “celebration” event following the murder.

The John Bazzano murder has been covered by other sources and not all details will be included here. In summary, the Calabrian Pittsburgh rappresentante John Bazzano was accused of having the three Neapolitan Volpe brothers murdered in 1932. An ethnic component to the conflict was evident in that the Volpes were allies of fellow Neapolitan Vito Genovese, then Charlie Luciano’s underboss, while Bazzano was said to have ties to fellow Calabrian Albert Anastasia, underboss to Vincenzo Mangano. Genovese took issue with the Volpe massacre and John Bazzano was called to account by the Commission in NYC. An underworld trial was held and the Commission ruled against Bazzano, who was executed in New York following the meeting. Some sources allege John Bazzano was killed during the meeting itself.

The men arrested by police were not random. The presence of Pittsburgh visitors speaks for itself given it was their boss John Bazzano on trial. Charles Spallino was from the same Calabrian hometown as Bazzano, while Michael Bua, Michael Russo, and Frank Adragna were Sicilians. Pittsburgh was noted for taking in a significant faction of mainland Italians at a time when most American Families remained predominately Sicilian. John Bazzano and Charles Spallino were from the town of Palizzi Marina in Reggio Calabria and their close association with local Sicilian figures is firmly established. Spallino surfaced in connection with the murder of a previous Pittsburgh boss in 1929, the Sicilian Stefano Monastero from Caccamo, showing he was involved in high-level Pittsburgh activities on an ongoing basis and this included the murders of two Family rappresentanti; Spallino was also charged in another underworld murder during this period.

Bua and Russo, both named Michael, descended from Palermo province, with Bua’s hometown of Trabia producing other Pittsburgh members the Limas, one of which was Sam who moved to San Francisco and became the Family consigliere in the late 1920s while his nephew Tony became the San Francisco boss for a period beginning in the 1930s. Tony Lima was an informant and told the FBI he was inducted into Cosa Nostra by Pittsburgh boss Stefano Monastero, whose murder was linked to 1932 Bazzano arrestee Charles Spallino as mentioned above. Michael Russo descended from Cerda while Frank Adragna traced his heritage to Alcamo, Trapani.

Santo Volpe’s position as Pittston boss makes his attendance unsurprising, the underworld trial of another Pennsylvania rappresentante providing an obvious regional motivation for him to be there. His aide Angelo Polizzi was an influential Pittston member who would transfer to Detroit where Polizzi’s son Michael married into the Detroit Family leadership and became a top administrator in the organization. These Pittston representatives were from Caltanissetta, drawing back to Palazzo Adriano, the hometown of arrestee Ciro Gallo, as the Parrinos described earlier in this article were Palazzese members of the Pittston Family and Angelo Parrino married the daughter of boss Santo Volpe’s compaesano Stefano LaTorre, one of the founding members of the Family who Volpe first arrived to from their native Montedoro.

The Buffalo emissaries who attended the Bazzano affair were similarly connected to the highest levels of mafia leadership. Paolo Palmeri’s brother Angelo is believed to have been underboss to Joe DiCarlo, the first known rappresentante of Buffalo and father to Paolo’s fellow attendee Sam DiCarlo. Paolo Palmeri was from Castellammare del Golfo like another dominant faction in Buffalo and he was close to his paesani in the Bonanno Family. Both of the dominant compaesani factions in Buffalo were well-represented by Palmeri and Sam DiCarlo, the DiCarlos being from Caltanissetta province like the Pittston attendees and related by marriage to their Vallelunga-born compaesano Tony Bonasera of the Colombo Family, Bonasera being among the 1932 arrestees as well.

“Peter Lombardi” is the most enigmatic of those in attendance. His name is alternately spelled “Lombardo” in some accounts and his age of 50 places him at the older end of the spectrum, suggesting he was not a new face to Cosa Nostra. His exact affiliation is unknown and his residence in Trenton makes it difficult to pinpoint which mafia group he represented.

The Philadelphia and DeCavalcante Families had members living in Trenton by 1932 and Gambino members were eventually inducted there. Later sources state Trenton rackets were operated in various partnerships between representatives of these three Families and “Peter Lombardi” was evidently important enough to visit New York for the underworld trial of a national boss. The men detained in connection with the John Bazzano murder all came from the East Coast and though the other two Pennsylvania Families are represented, there was no clear Philadelphia presence at the meeting. Philadelphia’s close relationship with nearby Trenton could indicate “Lombardi” served as an emmisary for the Philadelphia Family.

Further research indicates “Peter Lombardi” was Pietro Giallombardo. Giallombardo was from Belmonte Mezzagno, linking him with the many Philadelphia members from that village as well as fellow Bazzano murder arrestee Giuseppe Traina of the Gambino Family, who himself had a close relationship to his Philadelphia compaesani. Pietro Giallombardo’s brother Giuseppe was a prominent counterfeiter also affiliated with the early Gambino Family and Giuseppe Giallombardo had an associate named Salvatore Traina. The Gambino Family’s presence in Trenton and Pietro Giallombardo’s 1932 arrest with Traina make it difficult to place him given he’d fit well with both the Philadelphia Family and the Gambinos. Outside of formal association, Giallombardo was the only representative arrested for the Bazzano murder who lived in New Jersey at the time.

Albert Anastasia was tied to John Bazzano through his Calabrian heritage and Anastasia’s rank in New York made participation in the affair a given. Fellow Gambino Family arrestee Giuseppe Traina however was Sicilian and he was by this time a capodecina. However, former Gambino captain Michael DiLeonardo knew Traina’s son Mario, who later succeeded his father as capodecina, and other proteges of the elder Traina who told him Giuseppe had once been part of early boss Salvatore D’Aquila’s administration, serving as consigliere.

Michael DiLeonardo’s grandfather Vincenzo, known as “Mr. Jimmy”, was a Gambino capodecina under Salvatore D’Aquila and a close personal friend of Giuseppe Traina. The DiLeonardos and D’Aquilas even shared a baptismal relationship, Salvatore D’Aquila serving as godfather to DiLeonardo’s son Anthony, Michael’s father. Michael DiLeonardo identified his grandfather Jimmy as a partner in Traina’s Empire Yeast Company. Records show New Jersey Gambino capodecina Antonio Paterno was another partner, as was New Jersey-based John Cappello Sr., from Belmonte Mezzagno like the Trainas. Cappello would move to Philadephia where an FBI report states he held the position of capodecina for a time. His son John Jr. would become a capodecina under Angelo Bruno.

A Philadelphia branch of Empire Yeast was run by another family from Belmonte Mezzagno who were all made members, the Scafidis. A partner in this branch was Philadelphia member Antonino Calio from Castrogiovanni, near Bonanno leader Angelo Caruso’s hometown of Leonforte in Enna province. Pittsburgh had its own branch of Empire Yeast under Family boss Giuseppe Siragusa. The president of Empire Yeast in New York before Giuseppe Traina was Antonino Cecala, a well-known counterfeiter from Baucina close to former capo dei capi Giuseppe Morello, and another partner in the business was the Corleonese Tommaso “Tom” Gagliano who became official boss of the Lucchese Family in 1931.

Another New York partner with Lucchese connections was Domenico Dioguardi from Baucina, a compaesano of Antonino Cecala. Tom Gagliano’s own paesano Giuseppe Morello was himself involved with Empire Yeast, by this time holding an influential position under Genovese rappresentante Joe Masseria. Cecala had been a member of Morello’s original Family and in the 1920s could have been a member of the Lucchese Family, which included other Baucinesi, or he may have followed Giuseppe Morello into the Genovese Family.

The Lucchese and Genovese Families were originally part of a Family of Corleonese compaesani run by Giuseppe Morello prior to his counterfeiting conviction many years previous and the organization was split in the early 1920s after Morello’s release from prison. Giuseppe Morello was involved with an earlier mafia “super company” in the New York lathing industry that included Empire Yeast partners Antonino Cecala and Tom Gagliano. These opportunities to partner with other top mafiosi were attractive to all of those involved and facilitated cooperation even between rivals.

Yeast companies typically funneled resources into alcohol production, so the heavy collaboration by high-ranking members in different cities provided these men with legal and illegal financial incentives. These activities were also marked by underworld volatility. Antonino Cecala was killed in 1928 followed by Giuseppe Morello in 1930, then Giuseppe Siragusa in 1931. The Morello and Siragusa murders were not the result of business, but political machinations during and immediately after the Castellammarese War while Cecala’s violent death is largely mysterious. Regardless of these violent deaths, the totality of the partnership evidenced in Giuseppe Traina’s company speaks to the stature sources like Nicola Gentile and Michael DiLeonardo assign to him.

As with Giuseppe Traina, Michael DiLeonardo knew his grandfather to be a dear friend of Paolo Palmeri from Buffalo who was arrested with Traina in 1932 after the Bazzano murder. Immigration records confirm the relationship, as a 1924 ship manifest shows Jimmy DiLeonardo and Paolo Palmeri traveled to Italy together during a period when Salvatore D’Aquila is reported to have sent American mafia representatives to Palermo. Among the asides Michael DiLeonardo heard coming up in Brooklyn was that Salvatore D’Aquila was particularly close to Buffalo. D’Aquila’s choice of compare Jimmy DiLeonardo and Paolo Palmeri as emissaries to Palermo was a reflection of American mafia politics, as were the men arrested later for the John Bazzano murder.

Michael DiLeonardo knew Giuseppe Traina, who he called “Don Piddu”, to have served as an advocate for Salvatore D’Aquila’s relatives in the years following the capo dei capi’s murder. This is consistent with Nicola Gentile, who described Traina as an unrelenting D’Aquila loyalist who covertly worked against Joe Masseria’s national leadership during the early 1930s while remaining diplomatic in his open interactions with these rival figures.

Though the details of these various meetings and their corresponding politics are not known to Michael DiLeonardo generations later, the nature of these intertwined national relationships in early Cosa Nostra are not lost on him. What is revelatory to us was common knowledge in the Sicilian-American mafia subculture he grew up in. It was casual conversation among Gambino members who shared roots in the old D’Aquila regime.

Further evidence of D’Aquila representatives being sent to Palermo is a 1925 ship manifest showing Giuseppe Traina and future Family boss Vincenzo Mangano traveled to Italy together the year following DiLeonardo and Palmeri’s trip. These events show that in addition to attending important meetings within the United States, Paolo Palmeri and Giuseppe Traina also served as American representatives to Sicily during the same era. Nicola Gentile and other sources confirm there was continual travel and high-level contact between the top leadership of American and Sicilian Cosa Nostra, though they had separate governance. The mid-1920s were significant because sources in Italy like Dr. Melchiorre Allegra said Salvatore D’Aquila sent emissaries to help with the brewing Palermo war and it appears Palmeri and DiLeonardo, then Traina and Mangano were among these D’Aquila representatives which is unsurprising given the known stature of each man in America.

Paolo Palmeri later moved to New Jersey and Michael DiLeonardo recalled Palmeri attempted to arrange the marriage of his daughter to Michael’s uncle John DiLeonardo after World War II. Palmeri offered John a significant financial incentive, though Michael’s uncle turned the offer down in favor of an engagement he made prior to serving in the war. The DiLeonardo-Palmeri marriage didn’t pan out, but Paolo Palmeri’s interest in crossing bloodlines with high-ranking members of New York Families is evident from intermarriage between the children of Palmeri and New Jersey Genovese capodecina Willie Moretti. Palmeri’s son would marry a daughter of Moretti and Willie Moretti served as an acting member of his Family’s administration at the time, an example among many of mafia clans marrying within their own peer group.

Paolo Palmeri was active in the Buffalo Castellammare del Golfo Society as the mutual aid group’s “toastmaster”, serving as a “principal speaker” for the club spanning many years. Endicott had its own branch, as did Brooklyn. These groups held joint statewide conferences for all of the New York Castellammare del Golfo Societies where Palmeri carried out his speaking duties even after moving to New Jersey. Other committee members for these state conferences were Endicott-based Pittston Family members Bartolo Guccia and Emanuele Zicari, the former from Castellammare like Palmeri and the latter from Nicola Gentile’s hometown of Siculiana in Agrigento.

In addition to the underworld trial where John Bazzano’s fate was decided, another meeting where Paolo Palmeri served as a high-level representative occurred the year previous, in 1931. Palmeri was arrested in Chicago with the Marlboro-connected Bonanno leader Angelo Caruso and local Chicago mafia figures on suspicion of kidnapping. The men were accused of participating in an ongoing kidnapping ransom scheme that targeted “100 victims”. This accusation was an absurdity given Palmeri and Caruso’s true purpose for being in Chicago.

Follow-up investigation cleared Paolo Palmeri and Angelo Caruso of wrongdoing after their kidnapping arrest and they were released, though police were aware of rumors surrounding national underworld meetings in Chicago during this period, incorrectly devaluing these meetings as racket-motivated conferences of the “Al Capone mob”. Many sources, including Nicola Gentile, Joe Bonanno, and FBI recordings of Stefano Magaddino confirm Al Capone graciously hosted these Chicago affairs but these were not “syndicate” meetings directly concerned with crime and rackets, rather they were high-level Cosa Nostra meetings where significant administrative decisions were made.

Major meetings were held in Chicago during and after the Castellammarese War in 1931. It was at one of these meetings in late 1931 that the national leadership established the Commission. Stefano Magaddino was recorded admitting he was “made” a member of the Commission in Chicago at this time and Paolo Palmeri may have attended as an aide to his boss and compaesano Magaddino. His status as an emissary to Sicily in 1924 and New York in 1932 add significance to his presence in Chicago in 1931.

Paolo Palmeri’s November 1931 arrest in Chicago was two months after the murder of Salvatore Maranzano and Palmeri’s fellow arrestee Angelo Caruso was serving as acting boss of the Bonanno Family following Maranzano’s death. Caruso was said to have held this position for eight months and the FBI recordings of Stefano Magaddino similarly describe Caruso participating in these meetings. Palmeri’s presence with Caruso further adds to his ongoing reputation in Bonanno circles though Palmeri was part of the network’s Buffalo branch.

Though his profession as an undertaker was grim, Paolo Palmeri was a charismatic personality as is evident from his “toastmaster” role at compaesani mutual aid affairs and his role as a high-level mafia representative in Sicily, Chicago, and New York in 1924, 1931, 1932. The choice of “Paolino” Palmeri as a Buffalo representative for these important mafia meetings potentially informs us about the personality types selected for these duties. Charisma is a factor in mafia politics, as it is in any form of government.

Descriptions of similar meetings in Joe Bonanno and Nicola Gentile’s autobiographies illustrate how charisma was valuable currency in Cosa Nostra, with figures like Salvatore Maranzano gaining incredible political momentum through performative speeches. Though Maranzano was known for his explosive outbursts, leaping on tables and proclaiming what Stefano Magaddino described as “speculations”, descriptions of other national administrators like Giuseppe Traina show a more careful and considerate navigation of the political climate.

Michael DiLeonardo’s knowledge of Giuseppe Traina’s consigliere position under Salvatore D’Aquila is consistent with Nicola Gentile’s description of Traina, who Gentile says operated at the highest levels of national politics in the 1920s and the Belmontese Gambino leader served as one of the top mediators during the Castellammarese War between 1930-1931. Though Gentile doesn’t identify the exact position Giuseppe Traina held in the Family at the time, Gentile described Traina serving as acting capo dei capi for Salvatore D’Aquila during Assemblea Generale meetings, including a 1920s underworld affair again involving Pittsburgh. Traina also had close ties to another Pennsylvania city where he exercised authority and offered administrative guidance.

Giuseppe Traina’s compaesani in Philadelphia held high-ranking positions in their local Family for decades and sources confirm Traina served as a designated mediator, advisor, and national representative for the Philadelphia leadership as early as 1920. This arrangement continued until at least 1970. Traina was reported to have been involved in the election of early Philadelphia boss Salvatore Sabella as well as that of Angelo Bruno nearly 40 years later, even remaining influential for over a decade after that. Sabella was from Castellammare del Golfo like Paolo Palmeri while Bruno was from Villalba, a neighboring comune to the Buffalo-connected Vallelunga in Caltanissetta and Angelo Bruno’s first cousin Calogero Sinatra served as boss of Vallelunga for a time.

Though a Philadelphia FBI source indicated Giuseppe Traina helped select Salvatore Sabella as the first local mafia boss around 1920, other accounts assert there was already an organized Cosa Nostra presence in the city. Nicola Gentile said in his memoir that his Cosa Nostra induction took place in Philadelphia in the first years of the 20th century and though Gentile doesn’t say who or what this Family consisted of, this initiation provided him with formal recognition throughout the United States and Sicily for the rest of his life, hardly a loose-knit “Black Hand” gang as contemporary coverage often framed Cosa Nostra.

Senior Philadelphia member and FBI informant Harry Riccobene was inducted in 1927 and told the FBI there were multiple Philadelphia Families earlier on that were eventually combined into one regional Family. He echoed this in extensive interviews with Philadelphia mafia historian Celeste Morello decades later, identifying early bosses and members of separate Families whose small membership was formed along compaesani lines derived from Sicily. One of these organizations descended from his hometown of Castrogiovanni and included Empire Yeast’s Antonino Calio, mentioned earlier.

Harry Riccobene’s father was a Philadelphia member prior to 1920 and he traced his mafia heritage back to Sicily. Riccobene specifically said his father was a member in Philadelphia before Salvatore Sabella was boss. His information suggests Sabella was not the first Cosa Nostra boss in Philadelphia, but the first rappresentante of a unified Philadelphia Family after these smaller groups merged together. One of the original Philadelphia Families identified by Riccobene via Celeste Morello was comprised of members from Giuseppe Traina’s hometown Belmonte Mezzagno and a number of these men would hold the rank of capodecina simultaneously under later bosses, including the Cappellos and Scafidis who worked with Traina through Empire Yeast.

The son of one Belmontese captain was Rocco Scafidi, an inducted member who cooperated with the FBI from the 1960s through much of the 1970s. Shortly after his early 1950s induction he was shelved for various infractions, including an unsanctioned murder. An underworld trial was held where a visiting Giuseppe Traina successfully bargained for Scafidi’s life. Scafidi’s membership was later reinstated at a ceremony (note he was not re-inducted) and he told the FBI his uncle Joe Scafidi, Rocco’s capodecina, wept “tears of joy”. Rocco Scafidi’s brother Salvatore, another Family member, managed the Philadelphia branch of Empire Yeast and an FBI report shows the younger Scafidis called Giuseppe Traina “uncle”.

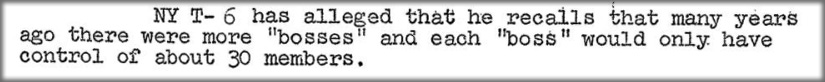

A similar merging of organizations took place in Chicago, where a separate Chicago Heights Family was combined with the main Chicago Family after the Chicago Heights leaders were killed, with indications the same process played out in Gary, Indiana, where a small contemporary Family allegedly existed. Nicola Gentile confirmed Chicago Heights was a separate Family from the main Chicago group and later FBI investigation shows continuity between this earlier group and a Chicago Heights decina under the Chicago Family. The murdered Chicago Heights leaders were from Caccamo, the same hometown as Pittsburgh rappresentante Stefano Monastero who was shot to death in the mid-late 1920s. The Caccamese bosses in both cities were killed in 1926 and 1927, respectively.