Fiction Meets Reality in the Gambino Family's Garofalo Crew

The unpublished history of one of New York's oldest groups, with assistance from Michael DiLeonardo.

The FBI’s investigation into the Gambino Family is among the most comprehensive thanks to high-level informants and government witnesses, not to mention the publicity brought to the Family by infamous bosses like Albert Anastasia, Carlo Gambino, and John Gotti. Though law enforcement was able to accurately identify the Family’s hierarchy, captains, and a majority of its members dating back to the early 1960s, the Gambino Family is one of the largest Cosa Nostra organizations in New York City and historians now believe it to be oldest. As a result, many details have not been fully reported or contextualized until now.

Though the organization has undergone significant changes throughout its long history, the Gambino Family has retained factions that balance modern mafia activity with a museum-like history of the group’s roots. One of these crews was and perhaps still is active in Brooklyn and Manhattan, representing significant remnants of the Family’s origins and Sicilian lineage while providing a direct link to 1970s pop culture. A massively overlooked figure in this antique Gambino decina once served as the leader of the crew and provides a familial link to the most celebrated mafia movie in entertainment history. Other members of this crew are no less relevant and this article addresses their essential role in the development of American Cosa Nostra.

This story could not be told without a later figure of note whose willingness to collaborate for this article led to its writing. He is the living history of this group and bridges a gap between the past and present.

A Crew With History

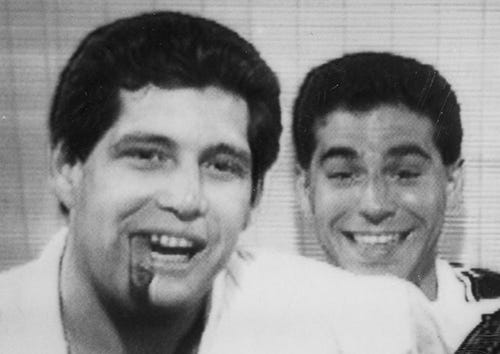

Michael DiLeonardo was raised in Bath Beach, Brooklyn, and inducted into Cosa Nostra on Christmas Eve 1988 alongside boss John Gotti’s son Junior, joining the crew of Jackie D'Amico, an outgoing captain known to the public for his close friendship with the senior Gotti. D’Amico is frequently seen smiling a step or two behind Gotti, sometimes holding an umbrella or opening a car door as photographers captured his boss going to and from court. FBI surveillance shows D’Amico’s constant presence at the notorious Ravenite Social Club in Little Italy, leaving little question as to the role this Manhattan-based captain played in the Gotti regime during its peak years in the 1980s and 1990s.

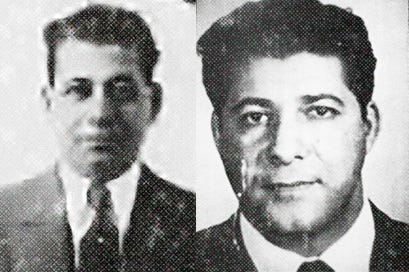

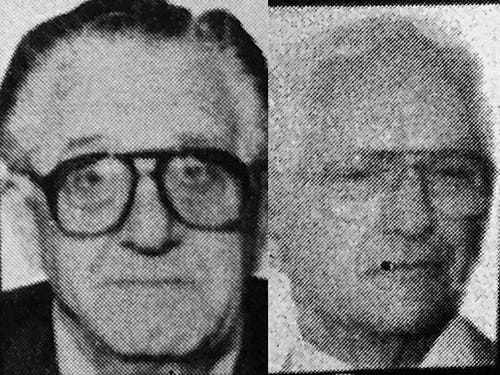

D'Amico inherited a crew with roots far deeper than the Gotti regime, though. Michael DiLeonardo himself was evidence of this, as was his mentor Paul Zaccaria and another one of DiLeonardo’s guides, Jerry D'Aquila. Zaccaria was the nephew of early Gambino boss Salvatore “Toto” D'Aquila and Jerry was Toto’s son, both men having been inducted into Cosa Nostra decades before DiLeonardo. Michael's grandfather Vincenzo "Jimmy" DiLeonardo was the first known capodecina of the crew, holding rank under Toto D’Aquila through the latter's violent death in 1928.

By 1988, sixty years had passed since the elder D'Aquila's murder, but the decina still reflected its early origins and served as a living piece of Gambino Family history. Jimmy DiLeonardo did not serve as capodecina under later Family bosses but remained a senior figure who crew members consulted and deferred to until his 1971 death at nearly 90-years-old. Following his own induction, Michael was told the D'Amico crew formerly run by his grandfather was one of the two longest-running crews in New York, the other being that of Mario Traina, son of Giuseppe. Most of the Traina crew was based in Brooklyn and Staten Island and the two Gambino groups maintained a close relationship.

Michael DiLeonardo learned the old DiLeonardo and Traina crews were allowed to continue uninterrupted without having been broken up or split, tracing their origins to the 1920s if not earlier. In contrast, it was common in the Brooklyn faction of the Gambino Family for the various overlapping crews to be disbanded or divided, with members assigned to new captains or other crews. It is significant that these two crews remained intact over many generations of conflict, leadership turnover, and political intrigue.

Giuseppe “Don Piddu” Traina served as Toto D'Aquila's consigliere and acting capo dei capi at national mafia events during the 1920s, the latter role confirmed by Nicola Gentile, before taking on the position of capodecina for the remainder of his long life. He also served as the Family’s messaggero to Philadelphia for at least fifty years, an arrangement that stemmed from Piddu Traina’s close relationship to compaesani from his hometown of Belmonte Mezzagno in that Family’s Sicilian faction. After becoming a member himself, Michael DiLeonardo learned of Piddu Traina’s administrative position under Toto D’Aquila and grew up knowing “Don Piddu” to be an esteemed senior figure alongside his grandfather, the two men naturally being close friends. Men like Traina, Jimmy DiLeonardo, and Paul Zaccaria’s father Calogero, known as “Don Caliddu”, who was married to the sister of Toto D’Aquila’s wife, facilitated the eventual entry of the younger Zaccaria and Jerry D’Aquila into the organization, ensuring continuity between the Toto D’Aquila era and the modern Gambino Family.

Though membership skipped a generation, Michael was the third DiLeonardo to join the Gambino Family, following his grandfather as well as his great-grandfather Antonino. Antonino DiLeonardo died of natural causes in 1927 at the age of ninety, placing him among the eldest mafia members in New York City before his death. Though he never became a member, Michael DiLeonardo’s father Tony served as Calogero Zaccaria’s driver until the aging Zaccaria was murdered in 1948 for repeatedly making unauthorized loans on the Brooklyn docks. The 61-year-old Zaccaria was shot to death on the front porch of his Bath Beach home by unidentified assailants, a murder that baffled authorities. Michael was later told that his grandfather Jimmy previously defended “Don Caliddu” for the same offense on multiple occasions but “could no longer sit” for Zaccaria after he continued to defy orders.

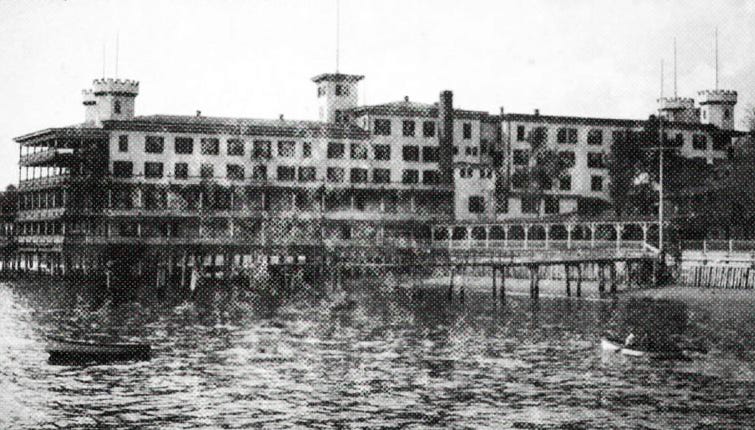

Calogero Zaccaria had monetary resources stored in different banks under various aliases and never told his family “who had the rest of it.” Though Tony DiLeonardo was officially on record as an associate of his father Jimmy, his close relationship to Zaccaria led him to assist Zaccaria’s widow in her attempts to claim Calogero’s hidden assets. She was denied access given none of the bank accounts used his true name, thus the family was unable to retrieve whatever money he had saved. Calogero Zaccaria also had a financial interest in the waterfront Fort Lowry Hotel on 17th Street in Bath Beach where the Zaccaria and DiLeonardo families spent time socializing.

In addition to his mentorship under Calogero Zaccaria, Tony DiLeonardo was also the godson of Zaccaria’s brother-in-law Toto D’Aquila but the capo dei capi’s savage death led Jimmy DiLeonardo to bar his son from attaining membership, perhaps a superstition drawn from the archaic rituals of Sicilian mafiosi. The symbolic importance of compari relationships are essential to wider Italian culture, but often play an even greater role among Cosa Nostra members. In this case the Gambino Family boss and one of his top captains became compari, the significance of which requires no explanation. The exact role D’Aquila’s murder played in limiting Tony DiLeonardo’s mafia status is unclear, with Jimmy DiLeonardo simply stating, “Nobody gets my son, he is not for this life.” An unidentified Cleveland mafioso served as the godfather to another one of Jimmy’s sons and he too was murdered. None of Jimmy DiLeonardo’s three sons became Cosa Nostra members.

Tony DiLeonardo apparently had another opportunity to became a made member in the 1950s, recalling to Michael how Carlo Gambino asked Jimmy DiLeonardo about the prospect of inducting Tony into the Family. Based on the timeline, this may have been when Carlo Gambino was consigliere of the Family in the years before he became boss. Michael has stated in government testimony how Carlo Gambino was a reverent visitor to his grandfather’s house, which was next door to Michael’s own; Gambino and other prominent figures paid respect to Jimmy DiLeonardo and sought the senior mafioso’s counsel.

Though Carlo Gambino himself apparently felt Tony DiLeonardo was a viable candidate for the organization, Jimmy remained committed to his earlier decision and refused the offer, instead suggesting the Family induct his nephew Joseph Delmonico. Delmonico was related to the DiLeonardos through Jimmy’s wife and would later be inducted into the Gambino Family under Carlo Gambino’s relative Paul Castellano. A photograph from the 1980s shows Joe Delmonico as a guest in Castellano’s palatial home with a large group of high-ranking Gambino members.

When Michael DiLeonardo was promoted to capodecina of his own crew in the 1990s, his second cousin Joe Delmonico was one of the members assigned to him. Though the DiLeonardos and Delmonicos had an obvious path into the Gambino Family, two immediate relatives would gravitate toward the Colombo Family with tragic results. Joe Delmonico’s namesake son Joseph broke away from his father after a falling out and began using the alternate surname DeDomenico as an associate of the Colombo Family’s violent “Wimpy Boys” crew under longtime FBI informant and prolific murderer Greg Scarpa Sr. Michael DiLeonardo’s older brother Robert, known as “Bucky”, was also an associate of the Scarpas. Bucky DiLeonardo would be murdered by Greg Scarpa Jr. in 1981, while DeDomenico was killed by the Scarpa group in 1987. Bucky was not a made member but Joe DeDomenico had been formally initiated into the Colombo Family six years previous yet formal membership did little to prevent his murder.

Michael’s father Tony DiLeonardo is an exception among many of his relatives and friends in that he never became a formal member of the organization. His son Michael agrees with his grandfather’s decision, believing his father was better off not having been initiated into Cosa Nostra based on his temperament. Michael states that his father simply “did not have a filter for the life.” Regardless of his associate status, Tony was a confidant of his father Jimmy and still made a living as a gambler, eventually retiring to Florida around five years after the death of Jimmy DiLeonardo in 1971. Michael recalls his father leaving New York soon after Carlo Gambino died in October 1976.

Tony DiLeonardo would tell Michael countless stories about his son’s grandfather Jimmy, including investments in Piddu Traina’s Empire Yeast Company (a partnership between many high-ranking mafiosi), the Italian radio station WOV, and Bellanca Aircraft, a pioneering aviation company in Brooklyn. Bellanca Aircraft was owned by Giuseppe Bellanca, a native of Sciacca, Agrigento, where a powerful faction of early Gambino members also descended from. Though Giuseppe Bellanca has not been linked with mafia activity save his alleged partnership with Jimmy DiLeonardo, Jimmy was close friends with Bellanca’s Sciacchitano paesano Onofrio Modica, an early Gambino member whose son and namesake grandson would also join the Gambino Family. DiLeonardo’s hometown Bisacquino is near the border of Agrigento and DiLeonardo had a close relationship with the Gambino Family’s Sciacchitani group, suggesting this provided a connection to the esteemed Giuseppe Bellanca.

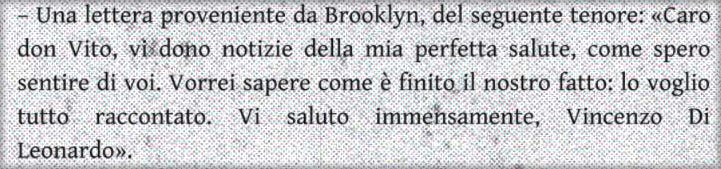

Tony DiLeonardo also traveled to Sicily with his father Jimmy in the late 1920s and told Michael about the DiLeonardo family’s ties to the infamous Vito Cascio Ferro, the boss of Bisacquino who Michael was told played a role in Antonino and Jimmy DiLeonardo’s immigration to New York. The relationship is confirmed by a 1909 letter from Michael’s grandfather Jimmy to Cascio Ferro, then several years removed from his own residence in New York City. Jimmy DiLeonardo was in his late 20s by this time and likely a Cosa Nostra member already given the early mafia’s tendency to induct young men, even teenagers. His correspondence with someone of Vito Cascio Ferro’s stature is further indication Michael’s grandfather was accepted in mafia circles by the first decade of the 1900s.

Writing under his true name Vincenzo DiLeonardo from his residence in Brooklyn, Michael’s grandfather inquired about a vague matter and showed great reverence for “Don Vito” when addressing him. The letter is believed to have arrived a short time after the murder of NYPD Police Detective Joe Petrosino in Palermo, of which Vito Cascio Ferro was a prime suspect. Michael’s father Tony told him how men from their ancestral hometown of Bisacquino were involved in the Petrosino murder.

The timing and coded nature of Jimmy DiLeonardo’s overseas letter to Vito Cascio Ferro could suggest DiLeonardo was intimately aware of the Petrosino murder plot, assuming Cascio Ferro was indeed one of the participants as is commonly believed. DiLeonardo was not without his own violent streak, as Michael was told how his grandfather was involved in the murder of a man accused of shooting a compaesano from Bisacquino in New York. Michael was told how the “revenge” murder concluded with the victim being placed in a baker’s oven for disposal; the bakery belonged to Jimmy DiLeonardo’s Sciacchitano friend Onofrio Modica. Census records confirm Modica was employed as a baker.

Contemporary investigators heard several other rumors from this early period involving mafia murder victims being placed in baker’s ovens. Two of these stories surfaced during the “Good Killers” case in the early 1920s where a group of Castellammarese mafia hitmen in the future Bonanno Family were said to have utilized an oven for disposal on at least one occasion, though a source also attributed this method to an additional murder connected to this group. Countless mafiosi were bakers by trade who ran their own neighborhood bakeries, Onofrio Modica being one of many, suggesting these different accounts were not confused but rather referring to a process that occurred multiple times given the convenience offered by mafia-owned bakeries. The smell would of course be damning and the practicality questionable, but Cosa Nostra is known to use every available resource within its insular network. Michael DiLeonardo heard about his grandfather’s own bakery murder from his father Tony as well as Onofrio Modica’s son Philip, a senior Gambino member who would report to Michael DiLeonardo after Michael’s promotion to capodecina.

Naturally Tony DiLeonardo also shared stories about his mentor Calogero Zaccaria and godfather Toto D’Aquila. D’Aquila has a mythical status among mafia researchers given the sixteen mysterious years he spent as both an early Gambino Family boss and national capo dei capi, but the DiLeonardos socialized with him and regarded each other as extended family. The D’Aquilas and DiLeonardos called each other “cousins” despite having no blood or marital relation. Later generations of Gambino members may have been unaware of the powerful Toto D’Aquila’s role in Family history but his influence was still alive in Bath Beach.

The respective murders of their fathers twenty years apart did not deter first cousins Jerry D’Aquila and Paul Zaccaria from joining the Gambino Family. Their surnames and lineage still had value in Brooklyn and the two men were fully-initiated members by the 1950s. Michael DiLeonardo believes Piddu Traina first proposed Jerry D’Aquila for membership and knows for certain that D’Aquila in turn sponsored Paul Zaccaria. Among later leaders who recognized their background was boss Carlo Gambino, identified as part of a secret faction during the Castellammarese War who quietly sought vengeance for the 1928 murder of Toto D’Aquila. Piddu Traina was described by Nicola Gentile as a key leader of this group as they sought to tactfully undermine D’Aquila’s murderers during the conflict. Jerry D’Aquila was still just a boy at the time of Toto’s death, having personally witnessed his father’s murder, but these relationships were kept intact as his father’s allies carried on as Family leaders.

Just as his father served as Calogero Zaccaria’s driver, Michael DiLeonardo followed a similar pattern when he served as Paul Zaccaria’s driver after coming of age. The younger Zaccaria and Jerry D’Aquila would go on to provide Michael with difficult advice based on their own experiences when DiLeonardo’s brother Robert was murdered by the Colombo Family in 1981: accept it and move on if you want to join the Gambino Family, or for that matter, if you want to remain alive yourself. They were speaking not for themselves but on behalf of Cosa Nostra and DiLeonardo did as they suggested. He was sponsored for membership seven years later at 33-years-old, continuing the mafia tradition of his lineage much as Jerry D’Aquila and Paul Zaccaria had under similar circumstances.

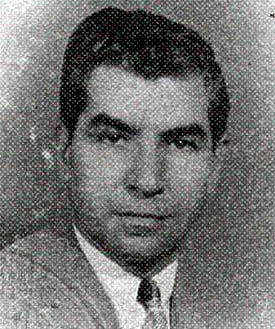

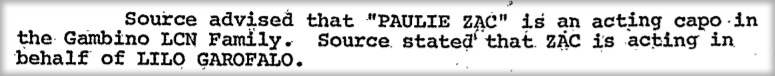

The crew’s eventual captain Jackie D'Amico was from Manhattan, as was his predecessor Olimpio "Lilo" Garofalo, who ran the crew from the early 1960s until his death in the 1980s. Though much of the crew was based in the Bensonhurst and Bath Beach area of Brooklyn, where Jimmy DiLeonardo operated and Toto D'Aquila himself lived for a time, the crews roots likely originate in Lower Manhattan where most of the known Cosa Nostra groups maintained a presence.

Michael DiLeonardo recalls that his grandfather once lived around Lower Manhattan’s Baxter Street where he operated on Elizabeth Street and a 1906 record shows him residing on the corner of Spring and Elizabeth. By World War I he was still living in Manhattan on Stanton Street. He subsequently moved to Brooklyn and was soon followed by the D’Aquilas and Zaccarias, though later figures like Lilo Garofalo and Jackie D’Amico are evidence the crew kept members in Manhattan. The D’Aquilas were living in the Bronx at the time of Toto’s murder, where Carlo Gambino and his brother Paolo were then living alongside Family leader and D’Aquila ally Frank Scalise, all from Palermo like D’Aquila, though the D’Aquilas would return to Brooklyn after the death of their patriarch.

A 1960s FBI report notes that Toto's son Jerry headed the crew as capodecina prior to Lilo Garofalo before facing demotion for financial infractions, a fact confirmed by Michael DiLeonardo. He knew Jerry to have been demoted for unpaid debts and mishandling money; senior figures like Jimmy DiLeonardo were frustrated with D'Aquila but ultimately forgiving of his conduct, as was the Family leadership. It is fortunate that Jerry D’Aquila did not suffer the same fate as his father and uncle, with Gambino leaders instead allowing him to continue on as a Gambino soldier until his death in the year 2000, seven years prior to cousin Paul Zaccaria’s passing. The crew also had other captains between Jimmy DiLeonardo and Jerry D'Aquila, all of them naturally predating Lilo Garofalo’s long tenure.

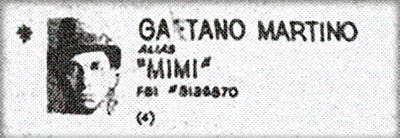

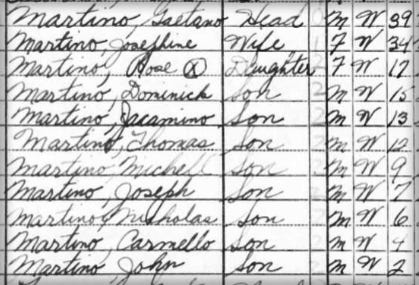

Though the exact succession and timeline is murky, Michael DiLeonardo was told the names of some earlier Garofalo crew captains. One of these was Gaetano "Tano Longo" Martino, a name who has thus far been a source of confusion for researchers. The Brooklyn-based Martino was well-known to law enforcement, being profiled by the FBN (Federal Bureau of Narcotics) and FBI both, the latter carrying him on lists of Cosa Nostra members beginning in the 1960s. However, the FBI was mistaken about the Family he belonged to. This article clarifies Gaetano Martino's affiliation and provides a bridge between reality and fiction: the Carlo Gambino and Vito Corleone Families.

Martino’s Shadowy Affiliation & Palermo Travels

Known as "Tano Longo" and “Tom Long” on the streets of Brooklyn, Gaetano Martino was a cigarette smuggler and suspected narcotics trafficker born in the city of Palermo in 1900. Though he lived and operated in an area of Brooklyn known for its strong Gambino presence, Gravesend, Martino was once carried by the FBI and thus mafia researchers as a member of the Genovese Family. Investigation into FBI files shows no definitive member sources who identified him with the Genovese Family, suggesting this designation was more speculative and came from Martino's association with a variety of Cosa Nostra members, including those under the Genovese Family. Some of the confusion may also come from similarities between his name and a senior Genovese capodecina active in Brooklyn: Gaetano Maiorana, nicknamed "Toddo Marino".

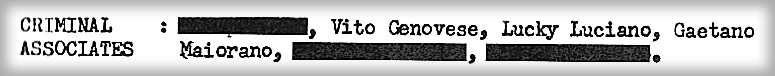

Adding to the confusion, Gaetano “Toddo Marino” Maiorana was often carried under the name Gaetano Marino on official documentation, a single-letter difference from Gaetano Martino. Beyond phonetic similarities linking the men, the FBN profile for Gambino member Gaetano “Tano Longo” Martino identifies Genovese captain Gaetano “Toddo Marino” Maiorana as one of Martino’s criminal associates, linking the two men further. With the exception of three redacted names, the only other associates listed for “Tano Longo” aside from Maiorana are Salvatore “Charlie Lucky” Luciano and Vito Genovese, both Genovese Family bosses. These factors likely contributed to his misidentification as a Genovese member as there are no Gambino Family figures listed nor members of any other Family to balance out these patterns of association. Gaetano Martino’s alleged relationship with two Genovese Family bosses and a capodecina would suggest he had significant status in Genovese circles but as is typical with FBN information, it does not necessarily indicate formal affiliation — a detail that was often lost on early law enforcement.

Interestingly, Michael DiLeonardo was told his grandfather Jimmy personally knew Charlie Luciano and the two men met in Manhattan with other mafiosi of the era. Luciano’s reputation has created a thick wall of mythology around his formative years, but it must be remembered that he was a real man and once regarded simply as an up-and-coming mafia figure like his contemporaries. Joe Bonanno identified Luciano as a capodecina under Joe Masseria just as Jimmy DiLeonardo held the same rank with Toto D’Aquila’s Family, making familiarity between the two men likely given their involvement in high-level New York politics of the 1920s and their mutual presence in Manhattan. In fact, some of Luciano’s earliest known associates were future Gambino members Stephen Armone and Joe Biondo.

Though Charlie Luciano is rightfully regarded as a proponent of Americanization within Cosa Nostra, he still earned mafia membership at a time when the old guard and its traditions dictated member conduct. Among this conduct was a spirit of comradery and connection between men from the same hometowns and regions of Sicily — indeed, these connections provided the blueprint for formal affiliation with a given Family and mafia association in general followed similar principals. Luciano descended from the inland Palermo village of Lercara Friddi, a short distance from Jimmy DiLeonardo’s hometown of Bisacquino. There is no reason to speculate the two men had a particularly close relationship or ever discussed their hometowns, but they were part of a subculture that prioritized these influences and the men could trace their origins to the same small piece of Sicilian geography which is interesting in its own right.

Michael DiLeonardo was told his grandfather Jimmy was also a close friend of Genovese capodecina Willie Moretti of New Jersey, though Moretti was a non-Sicilian and we can thus discount even a subliminal connection based on heritage. Further indication of DiLeonardo’s relationship to Moretti comes via former Buffalo member Paolo Palmeri, who Michael knew to be another close friend of his grandfather. Palmeri moved to New Jersey where he and Willie Moretti’s children intermarried and maintained close association. Jimmy DiLeonardo and Paolo Palmeri traveled to Sicily together in the mid-1920s and according to Michael their children also came close to intermarrying. Palmeri offered Michael’s uncle John a significant sum of money should he marry Palmeri’s daughter when he returned from World War II but John DiLeonardo was already committed to a woman he met prior to his service.

Jimmy DiLeonardo’s meeting with Luciano and friendship with Moretti mesh with Gaetano Martino’s alleged association with Moretti’s Genovese affiliates Luciano, Vito Genovese, and “Toddo Marino” Maiorana. DiLeonardo and Martino were leaders of the same crew at different times and may have formed relationships along similar lines. Federal law enforcement however struggled with Gaetano Martino’s exact position in the mafia network.

Famed government witness Joe Valachi’s decades of membership in the Genovese Family and willingness to provide the public with extensive information on mafia members allowed the FBI to create impressive yet imperfect charts of the New York Families, particularly Valachi’s Genovese Family. Gaetano “Mimi” Martino is included on the Genovese chart as a soldier in the Vincent Alo decina, citing Joe Valachi as the source of this identification. The chart’s inclusion of Martino is sourced from a December 1962 report by Special Agent James Flynn where a “Tony Martino” known as “Mimi” is identified as a Genovese member by Joe Valachi. Gaetano Martino was apparently confused with this “Tony”, though it would turn out Tony Martino may not have been a Genovese member either.

Agent James Flynn came to learn the Genovese-affiliated identification of “Tony Martino” originally came from an alleged interview that took place between Joe Valachi and the FBN early in Valachi’s cooperation. The FBI obtained this information from the FBN and mistranslated it into “Gaetano Martino”. In a subsequent 1963 interview between Agent James Flynn and Joe Valachi, Valachi was shown a photo of Gaetano Martino and denied knowing or recognizing him. Approximately five months later Agent Flynn again showed Joe Valachi a photo of Gaetano Martino along with a photo of underworld figure Antonio Martino and Valachi stated both men were unknown to him. Flynn stated Valachi had never given any indication in these interviews that he knew Gaetano Martino or anyone with a similar name. It should be noted the nickname “Mimi” is not typically used for Gaetano or Antonio, with Gaetano Martino’s known nickname of “Tano” being the common Italian diminutive of his given name; “Mimi” is typically derived from the name Domenico, the name of Gaetano Martino’s father in Palermo. The FBN’s earlier profile of Gaetano Martino lists the nickname “Mimi”, but Michael DiLeonardo only knew him as “Tano Longo”, another nickname known to federal agents.

It is clear from Agent Flynn’s multiple interviews with Joe Valachi that Valachi did not recognize Gaetano Martino, was not aware of him, and certainly could not place him or “Tony Martino” with the Genovese Family despite the FBN suggesting otherwise. It appears the FBN mistakenly identified “Tony Martino” as a Genovese member via Valachi, passed the report to the FBI, and this was further miscarried into Gaetano Martino appearing on the FBI’s widely-publicized chart of the Genovese Family. The chart includes other notable mistakes, with several prominent members of other Families incorrectly identified as Genovese members, among them Carmine Persico, Settimo Accardi, and Tony Caponigro. Whether these were actual misidentifications on the part of Joe Valachi or the result of a similar FBN-FBI documentation error is unclear. Given how the Martino mistake originated with the FBN, it also calls into question the FBN’s list of Gaetano Martino’s associates in the Genovese Family, though this list was developed earlier and independent from Joe Valachi’s cooperation.

Federal law enforcement provides no known documentation of Gaetano Martino’s relationship with Charlie Luciano in New York prior to Luciano’s incarceration in the mid-1930s, but he is often cited as visiting Luciano in Italy following the latter’s 1946 deportation. Some written accounts even suggest Martino was an attendee at the heavily mythologized “Havana Conference”. Lacking the resources to properly untangle the Havana rumor and given the unfortunate distortion and fan fiction found in most published descriptions of the alleged Havana meeting, this article will not explore this meeting in substance unless clarifying information becomes available.

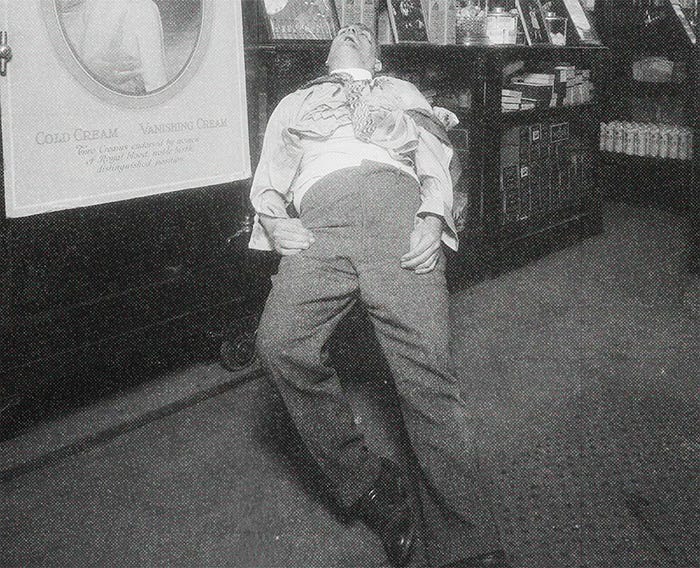

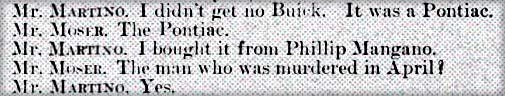

We do have a reliable source who confirmed Gaetano Martino’s interaction with Charlie Luciano in Italy: Martino himself. Called before the US Senate’s Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce in 1951, Gaetano Martino was asked about his general background and connections to mafia figures active on the Brooklyn docks. Martino denied relationships with most of the names brought forth by the inquiring senators. Martino did, however, admit to knowing Charlie Luciano and meeting him in Italy. He described traveling to Sicily during his time as an American citizen working for the Italian Merchant Marine in the mid-1940s and stated he socialized with Luciano twice during a stay in Palermo at the Grand Hotel et des Palmes, implying the meetings with Luciano were a matter of chance, running into him in the hotel lobby. Martino said he was in Palermo to visit his mother.

The period in question does coincide with Gaetano Martino’s travels as a seaman during and after World War II in the mid-1940s. Records show frequent maritime activity for the Sicilian-born serviceman in 1944 and 1945. His 1946 visit with Charlie Luciano would fit with the frequency of his travels abroad and indicates he used his time with the Italian Merchant Marine to visit his native Palermo. Whether Gaetano Martino’s visit with Luciano was by chance as he claimed or a planned affair is impossible to determine, but the US Senate’s questions indicated suspicion as to the purpose of Martino’s travels. He admitted to casually discussing Brooklyn with Luciano, a former resident of Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

Interestingly, the US Senate asked Gaetano Martino if he was the first American to have met with Charlie Luciano after Luciano’s arrival in Sicily, to which Martino pleaded ignorance. Gaetano Martino would not have been part of an exclusive club in visiting Charlie Luciano, as mafia figures from various US Families are believed to have paid visits to the former Genovese boss during their own trips to Italy. American Cosa Nostra members who were deported or chose to retire in Italy were also known to spend time with Luciano alongside Sicilian mafiosi under the watchful eye of Italian investigators. One of these men was Nicola Gentile, a powerful Gambino member and narcotics trafficker who returned to Italy in the late 1930s and secretly cooperated with the Italian Treasury, later writing an invaluable memoir. The Hotel et des Palmes was a popular meeting place for all of these men.

Martino admitted that although he had been a former longshoreman and “dock boss”, he had not worked since 1948 and received financial support from his children. Though he denied knowing the names of many mafiosi connected to the Brooklyn piers, he did admit knowing two men in addition to Charlie Luciano, these men being a greater indication of Gaetano Martino’s formal affiliation with the Gambino Family. Martino stated he had known Philip Mangano, murdered months before the 1951 hearing, and the testimony revealed ongoing association between Martino and Mangano. Philip Mangano was a high-ranking Gambino member and the brother of boss Vincenzo Mangano, who like Philip was killed that year by underboss Albert Anastasia during the Calabrian Anastasia’s powergrab. Another one of the few men Martino admitted knowing was Anastasia’s brother Tony Anastasio, who used a variant spelling of their surname and was an influential Gambino capodecina on the Brooklyn docks. The Mangano brothers were Brooklynites from Palermo like Gaetano Martino and his admitted relationship to Philip Mangano and Tony Anastasio indicate Martino had access to the Family’s leadership.

During his testimony Gaetano Martino acknowledged having heard about Philip Mangano’s murder, though he stated he read about it in the newspapers. In addition to his admitted association with Mangano, the US Senate alleged that Martino trafficked medical supplies to Italy on behalf of Philip Mangano during his travels. Authorities suspected Gaetano Martino of transporting “pharmaceuticals” to Italy in 1948 as part of these overseas trips, stating the belief that Martino carried out this activity for Philip Mangano at the request of Brooklyn mafioso Angelo Pero. They clarified that these were not “narcotic drugs” but rather medicine or medical supplies of some kind; Gaetano Martino nonetheless denied the allegation when asked.

Pero was identified by the FBI as a Genovese member though perhaps his affiliation deserves greater scrutiny given Gaetano Martino’s misidentification as a member of that Family. Still, these interactions involved high-ranking members of both the Gambino and Genovese Families so Pero would not be out of place no matter his formal affiliation. Regardless, the belief that Martino transported the medicine for Philip Mangano would suggest he took direction from his superiors in the Gambino Family. Mangano is suspected of holding the rank of capodecina in the Gambino Family, though sources like Nicola Gentile identified the younger Philip as a key aide who assisted his brother Vincenzo in national administrative matters.

Senators also inquired about Martino’s involvement in transporting a Buick automobile to Italy, to which he answered in the negative though later questioning would clarify these details. He did admit to having knowledge of an alien smuggling operation involving the Italian Merchant Marine ship he was stationed on. Mafiosi Sebastiano Nani and Biagio Palermo were two of the men who stowed away on the vessel and though Gaetano Martino admitted knowledge of this, he claims he was only told after reaching North America, the ship’s captain Nicholas Scaglione revealing the information. Scaglione was involved with Cosa Nostra in Tampa and descended from Alessandria della Rocca in Agrigento province, where the Gambino Family Arcuris and other members also traced their heritage; the Arcuris lived in Tampa prior to New York and had baptismal relationships with Tampa leaders the Trafficantes. Stowaway Sebastiano Nani was a former Colombo member who transferred membership to San Francisco prior to his deportation.

Gaetano Martino admitted another, more involved visit with Charlie Luciano a year later in 1947 when Martino vacationed to Italy with his wife. During this trip Martino allegedly met with Luciano “several times a day” according to investigators. The inquiry about transporting an automobile was clarified in connection to this trip, as Martino admitted to bringing a 1941 Pontiac to Italy at this time. He purchased the vehicle from Philip Mangano by his own admission.

Gaetano Martino also acknowledged being “pinched” by Italian authorities upon arrival in Naples for illegally carrying American cigarettes into the country, though he denied he was a smuggler despite the large quantity of cigarettes in his possession. Martino was fined 1,500,000 lire and the charges were dismissed. Though he initially planned to stay only three months, Martino stayed in Italy for a year during this trip and appealed the fine, which he said resulted in his having the monetary charge entirely removed, though a discrepancy emerged when the inquiring senator revealed a previous statement where Martino admitted paying a reduced fine.

Gaetano Martino lived in Palermo during his year-long stay in Italy where he again stayed in the Hotel et des Palmes. He also spent time in hotels on the mainland during trips to Naples and Rome, revealing how he paid very favorable rates for his rooms thanks to a connection made via his mother-in-law. Claiming to have seen Charlie Luciano “on and off” during his time in Italy, Martino said this primarily happened in Palermo when Luciano visited and the two men saw one another once or twice a week, though authorities believed the men saw each other daily.

The US Senate asked Martino if Charlie Luciano requested he take anything back to the United States with him when he returned, though the exact nature of the request was left vague. The overall line of questioning suggested authorities believed Gaetano Martino was involved in narcotics trafficking with Luciano. A drug trafficker named Michael Cisco was arrested in Canada in 1949 and law enforcement discovered a card in his possesion with “Gaetano Martino, Brooklyn” written on it, though Martino denied knowledge of Cisco. One senator’s comments to Martino implied the belief that Martino had knowledge of narcotics smuggling through his connections on the Brooklyn docks. The senator asked Gaetano Martino’s advice as to how drug trafficking could be prevented in the future, to which Martino simply stated he was a proud American who would be happy to help with this matter — if he only could.

Law enforcement assumed criminal intent by default when evaluating Charlie Luciano’s visits from American mafiosi, and perhaps there was some, but many of these visits appear to be social and it is improbable that Charlie Luciano was devising illegal schemes with every single one of his visitors. Some of the meetings may have been political in nature and Joe Valachi suggests Luciano continued to communicate advice and general directives to Genovese leaders during and after his incarceration, even while residing in Italy. Gaetano Martino’s confirmed involvement in cigarette smuggling between Italy and the United States would lend itself to criminal activities abroad, though it seems unlikely Martino would seek out the former boss of another Family for this purpose without an existing relationship. If such an arrangement existed, it’s likely Martino’s friend Philip Mangano and his brother Vincenzo authorized or encouraged these activities in collaboration with Charlie Luciano’s Genovese cohorts.

As evidenced by numerous FBN profiles, Gaetano Martino among them, associate lists alone are rarely indicative of formal affiliation and sometimes appear arbitrary. The FBN lacked inside knowledge of Cosa Nostra and drew their lists of association largely from outside observation. Men who were active in Little Italy for example were referred to as the “Mulberry Mob”, as if these men were one Family centered in Manhattan. In reality the “Mulberry Mob” comprised all of the five New York Families and members of these different groups associated with each other based on proximity, not through formal affiliation with the same group.

Some of the FBN’s lists of associates were presumably even based on one-off interactions. For example, arrestees from the ill-fated 1928 Cleveland meeting, which included national Cosa Nostra representatives of the era, are listed as “criminal associates” through the 1950s even when the men lived in completely different cities with no evidence of a sustained relationship. They attended one known meeting together early in their mafia careers where they faced arrest and publicity, leading law enforcement to link the men in perpetuity. The FBN shouldn’t be faulted, as their investigation into the mafia was revolutionary at the time and is still valuable to researchers today, but the information has to be properly understood and contextualized based on what we’ve learned about Cosa Nostra in more recent decades. While there is no doubt a degree of association existed between Gaetano Martino and Charlie Luciano, their interaction in Italy may have exaggerated their relationship in the eyes of contemporary law enforcement.

Some of the associations identified by law enforcement derive from men who were arrested together for criminal offenses earlier in their underworld career. This played little to no role in federal law enforcement’s understanding of Gaetano Martino, as his only significant arrest was a 1928 robbery charge that likely had no intersection with explicit Cosa Nostra activity. Aside from his cigarette smuggling case in Italy, his only other offenses were traffic violations that occurred in New York City. Martino was either marginally involved in street crime after the late 1920s or simply lucky to avoid arrest. Even if he had been arrested with other known mafiosi over the years, it may have told us very little about his affiliation with a given mafia Family.

Associate lists do reveal who interacted with one another but not necessarily where they belonged within the formal lines of mafia membership. Some Cosa Nostra figures show few if any outward appearances of belonging to their actual Family, with these members maintaining close friendships and forming partnerships outside of their own organization more often than within it. This was true in New York City then and it is equally true now, though we have greater resources today that make formal group identifications easier. Understanding the historic membership of early Cosa Nostra takes a greater degree of guesswork but it is informed by certain patterns that help us make educated guesses in the absence of definitive information. Gaetano Martino follows some of these patterns and they give further weight to his Gambino membership.

The Power of Geography

Mafia Families aren’t formed around general association but rather affiliation, a necessary distinction that must be understood in order to fully comprehend Cosa Nostra from the outside. In the absence of a member informant, government witness, or wiretap providing the FBI with these details, a member’s heritage and geography are strong factors in determining where he officially belongs, especially during the era discussed here. Thankfully Michael DiLeonardo reliably identified Gaetano Martino’s membership in the Gambino Family, but Martino’s heritage and residence in Gravesend follow a pattern that provides further evidence of his affiliation.

Both of them Sicilian, the similarly-named associates "Toddo Marino" Maiorana and "Tano Longo" Martino were active in Brooklyn and well-established among the mafia element in these neighborhoods. Maiorana lived in the South Slope neighborhood near the Brooklyn docks, an area populated by members of his own Genovese Family but with stronger representation from the Gambino and Colombo Families. A large number of members from the latter two Families migrated over time, building up greater concentrations further south in Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, and adjacent areas like Gravesend. The other Gaetano, “Tano Longo” Martino, followed this route, initially living in historic South Brooklyn near Red Hook where he was active on the Brooklyn docks as an on-and-off longshoreman before moving to Gravesend. Maiorana of the Genovese Family would remain northward.

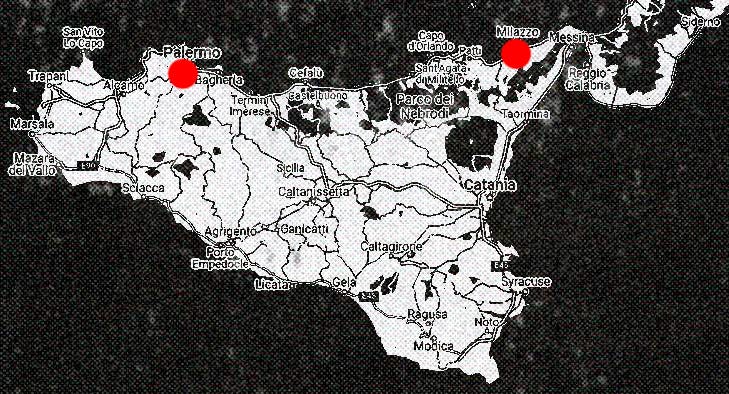

Genovese captain “Toddo Marino” Maiorana's Sicilian heritage made him a relative minority in the post-1931 Genovese family, who recruited heavily among Neapolitans and Calabrians by the 1920s, but there is no evidence Maiorana had ties to the subculture of Cosa Nostra in his native region. Born in Milazzo, Messina, on Sicily's far-eastern coast, Maiorano's introduction to Cosa Nostra was likely the product of criminal relationships formed in New York City alone. Coincidentally, Jimmy DiLeonardo married a woman from Messina though this was likely a product of local relationships, too, and not a result of overseas connections that sometimes dictated marriages among Italian immigrants and especially Sicilian mafiosi. However, the DiLeonardos did have deeper ancestral history in Acireale south of Messina before moving to Bisacquino so perhaps more was at play.

Practically touching the Calabrian toe of mainland Italy’s boot, Messina has more cultural similarities with Calabria than Palermo and investigations into the Sicilian mafia throughout its existence have shown little presence in Messina, with the Italian Senate noting this was in part due to its strong local government drawing influence from Central and Northern Italy, greatly limiting the impact of the oft-exploited “communal power” found in Western Sicily. In more recent years a formal Cosa Nostra organization has been identified in Mistretta while other nearby Messinese organized crime groups are described as “mafia-like”, seeming to mimic the structure found in Palermo without being a formal part of Cosa Nostra. Modern Messinese crime boss Gaetano Costa detailed his status not as a made member of the Sicilian mafia, but of the Calabrian 'Ndrangheta, the organization known casually as Calabria's "mafia". Costa revealed how the 'Ndrangheta established groups along Sicily's nearby eastern coastline, even in Catania, whose strong Cosa Nostra presence is exceptional in Eastern Sicily.

Though there are examples of significant Gambino members from Messina (interestingly from Barcellona near Maiorana’s hometown of Milazzo), it is perhaps unsurprising that "Toddo Marino" Maiorana ended up with the less Sicilian Genovese Family given the absence of Cosa Nostra in the northeastern corner of Sicily and the Genovese habit of recruiting outside the mafia tradition. Like Maiorana, the Gambino members from Messina likely joined their Family based on more circumstantial American relationships that directed their association toward established Gambino members, just as the Messinese Maiorana in the Genovese Family may have gravitated to his group for similarly localized reasons. Members from regions not typically associated with Cosa Nostra followed a less predetermined path, relying purely on proximity and shared activities to gain admission into a certain Family. There are exceptions, but early members from Western Sicily tend to be locked into much more obvious patterns that make their membership in a certain Family almost guaranteed based on the village or region they descend from.

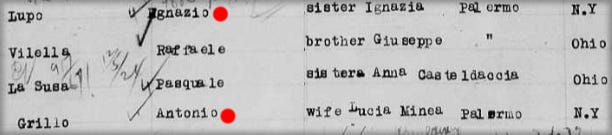

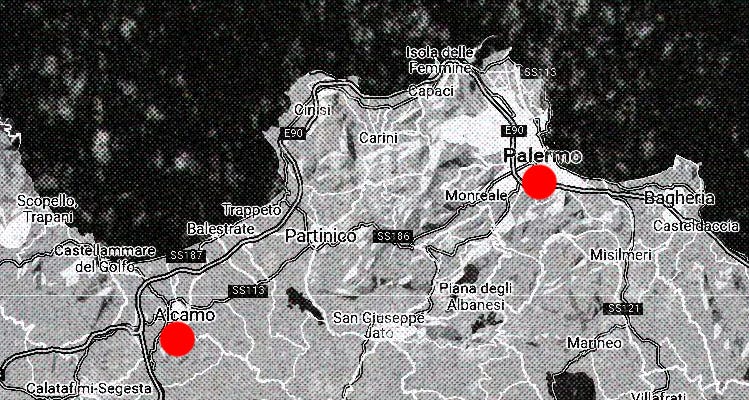

Gaetano “Tano Longo” Martino's roots in Sicily come from a location far more familiar to Cosa Nostra and specifically the Gambino Family: Palermo. Martino’s immigration records suggest he was living in the Palermo Centro neighborhood prior to entering the United States at age sixteen. Much of the Gambino Family came from urban Palermo and nearby suburbs, its first confirmed boss Ignazio Lupo being a product of central Palermo citta along with his successor Salvatore “Toto” D'Aquila. The three bosses who followed D’Aquila — Manfredi Mineo, Frank Scalise, and Vincenzo Mangano — were also the product of inner Palermo citta, making for nearly fifty straight years of Palermitano leadership that likely extends even further back before Lupo became boss.

Following a six year run by Calabrian boss Albert Anastasia after the murder of Mangano, the Gambino Family was led by two more Palermitano bosses for nearly thirty additional years, these bosses being Carlo Gambino and Paul Castellano, a duo related through blood and marriage. Given its history as one of the oldest crews in the Family, Lilo Garofalo's crew was naturally peppered with many men from Palermo, making Gaetano Martino part of a larger pattern in the group’s history that continues today. No evidence has been found linking Martino by blood or marriage to confirmed Sicilian mafiosi or older Gambino members, but his heritage in Palermo Centro would have immediately placed him in the Gambino Family network and the crew he belonged to helped form the foundation of this network.

Lilo Garofalo was born in Carini, a village on the western outskirts of Palermo citta, and Michael DiLeonardo knew Garofalo’s successor Jackie D'Amico to be an American-born Palermitano himself. Though other Gambino Family crews in Brooklyn included large numbers of Neapolitans and Calabrians who intermingled with Sicilians under the same capodecina, the two oldest groups — the old Jimmy DiLeonardo and Giuseppe Traina crews — remained mostly if not entirely Western Sicilian even into later generations. Both crews had strong representation from Palermo province, with the DiLeonardo crew under Lilo Garofalo maintaining a particularly strong concentration of members with urban Palermo roots in addition to the names already discussed. A breakdown of the Lilo Garofalo decina’s known membership from 1978 provided by LCNBios reveals many crew members with Palermo origins, a factor that would have likely intensified among earlier generations.

Gaetano Martino fits in perfectly with the Gambino Family given his Palermitano heritage and location in Gravesend, near Bensonhurst and Bath Beach, where many other Gambino Palermitani lived. The FBN noted that Martino also frequented Manhattan's Lower East Side, where the old DiLeonardo decina had other members nearby, including captains Lilo Garofalo and Jackie D'Amico. As exemplified by the DiLeonardos, D’Aquilas, and Zaccarias earlier, many Brooklyn mafiosi initially lived in Manhattan and migrated to Brooklyn. The Brooklyn-based members under Lilo Garofalo continued to visit Lower Manhattan where their captain held court in social clubs and businesses alongside other Palermo-rooted Gambino crews.

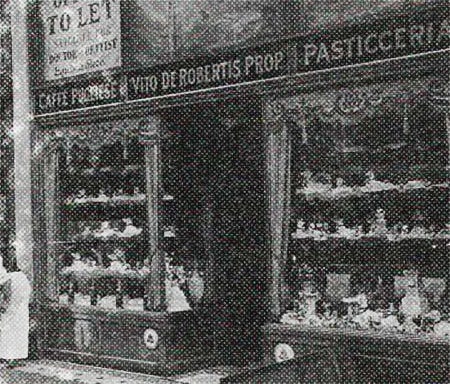

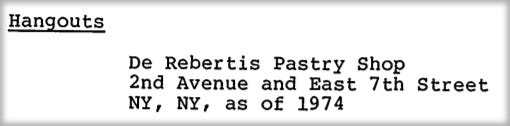

A particularly popular hangout for the crew by the 1960s was DeRobertis Pastry Shop in the East Village, as noted extensively in FBI logs. Michael DiLeonardo knew his grandfather to be a regular visitor at DeRobertis decades earlier and commented how the three Gambino crews known to hang out there were the Garofalo, Traina, and Joe Riccobono crews. Joe Riccobono was from an old Palermitano clan that produced Family leader Frank Scalise and an earlier Gambino power named Saverio Virzi, with additional Riccobono relatives and associates attaining powerful positions in the Family during and after his own time as captain. Riccobono is most known for serving as Carlo Gambino’s first consigliere, though health troubles resulted in a suicide attempt that curbed his activities in the 1960s.

Gaetano Martino’s documented jaunts to Lower Manhattan from his base in Brooklyn might well have included DeRobertis and other nearby establishments frequented by the Lilo Garofalo decina given his involvement with the same crew and the tendency for Palermitani to cluster there. An indication that Martino may have once held power closer to home in Brooklyn came via a 1958 FBI interview with Special Agent Joseph Amato of the FBN who was apparently familiar with the Palermitano mafioso’s activities in previous years. The FBN agent noted how Martino was once the “boss of a gang” active on the Greenpoint docks but had withdrawn from criminal activity in Brooklyn by the time of this 1958 interview.

How and why Gaetano Martino would be active in the northern Greenpoint neighborhood where the Gambino Family had fewer connections is unknown, assuming the FBN agent’s recollection was correct. As the Valachi discussion outlined, we have reason to doubt some of the FBN’s information on Martino given the miscommunication that led to his identification as a Genovese member. The FBI’s mistake regarding Gaetano Martino’s Genovese affiliation was apparently rooted in the FBN’s initial error in listing a “Tony Martino” as a Valachi-identified Genovese member, who was then confused with Gaetano Martino, and the FBI’s investigation into the error led them to suspect “Tony Martino” was a man named Antonio Martino who associated with Sonny Franzese, a Colombo member active in Greenpoint. Given this account of Gaetano Martino operating in Greenpoint again involved the FBN, it’s possible the FBN agent who described Gaetano Martino as a criminal “boss” on the Greenpoint docks was again confusing the two Martinos, though the Franzese-associated Antonio Martino does not appear to have been a significant figure — perhaps not even a made member.

On the other hand, if the FBN agent’s observation was correct and he accurately identified Gaetano Martino as the “boss of a gang” before 1958, it could indicate Martino held an influential position at the time. Gaetano Martino did have a history near the Brooklyn docks closer to Red Hook and admitted in his 1951 testimony to being a former “dock boss”, so perhaps the agent simply confused the location or Martino did in fact commute north to Greenpoint when the opportunity presented itself. Prominent Gambino members on the Brooklyn docks may have had access to Greenpoint given their pivotal role in the longshoreman trade.

Gaetano Martino’s testimony adds further evidence of his stature. His admitted relationships to Vincenzo Mangano’s brother Philip and Albert Anastasia’s brother Tony Anastasio, both Gambino leaders in their own right, shows Martino interacted at the highest levels of the Gambino Family and his friendship with Charlie Luciano of the Genovese Family indicates this extended to the leadership of other Families. The FBN agent’s account of Martino being a “boss” sometime prior to 1958 would complement Michael DiLeonardo’s knowledge of Martino as a Brooklyn Gambino captain before the 1960s and the agent’s description of Martino stepping back from criminal activity by the late 1950s may have coincided with his return to rank-and-file membership. Gaetano Martino does appear to have stepped back considerably by the 1960s. It’s apparent in either case that despite Gaetano Martino’s notoriety, federal agencies had difficulty placing him during the formative years of mafia investigation and some of their errors have persisted among researchers.

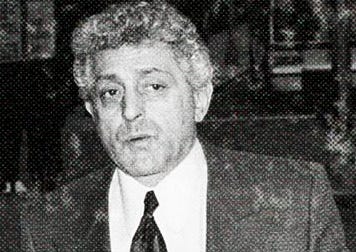

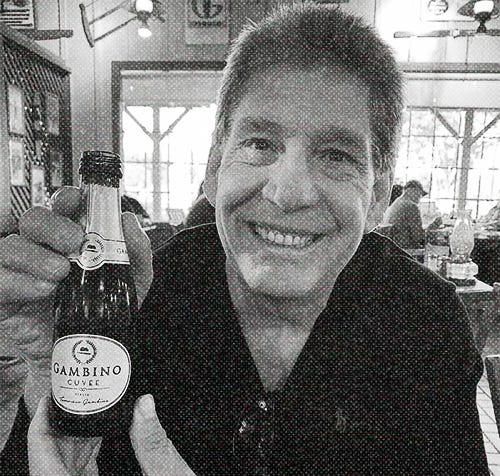

Unlike the federal agents of decades past, Michael DiLeonardo is far less confused about who Gaetano Martino was. After Michael DiLeonardo recounted how Martino had once been a capodecina of his grandfather's former crew, I gave him a little bit of pushback, mentioning that Marino was carried as a Genovese member by the FBI. With a chuckle, DiLeonardo said that "Tano Longo" Martino was "absolutely" a member of the Gambino Family and not only shared details on these connections but also provided an amazing revelation that connects to the mafia's foundations in American pop culture.

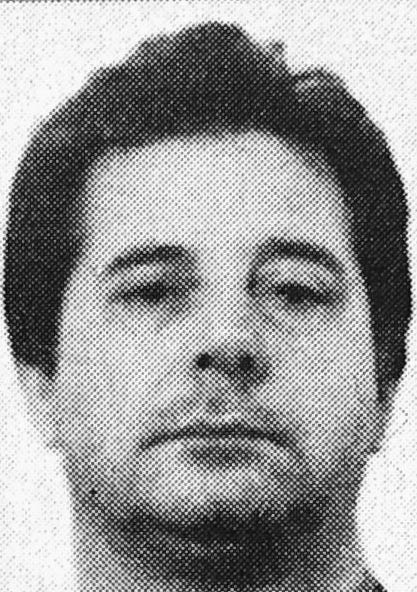

“Paulie Gatto” Knew His Role

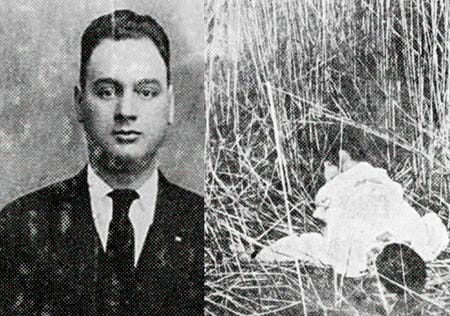

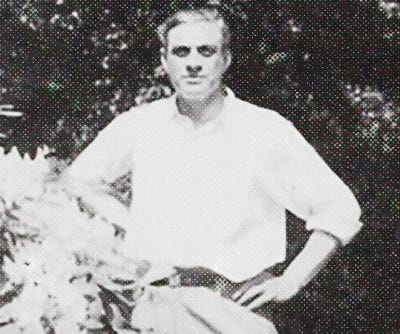

Michael DiLeonardo revealed how "Tano Longo" was not simply a one-time Gambino captain, but also the father of a noteworthy wiseguy — this one fictional. It’s not uncommon to find Cosa Nostra associates and relatives who played bit roles or served as extras in mafia movies, though it is rare for an actor with substantial mafia ties to make a permanent mark on the history of entertainment. Martino’s son did exactly that, albeit in a supporting role. His youngest son was a member of one of the most infamous mafia Families in Hollywood history: he was Paulie Gatto from the first Godfather movie.

Michael revealed that Johnny Martino, the actor who played Paulie Gatto, was one of Gambino member Gaetano Martino's sons, a fact well-known in Brooklyn. Any skepticism toward these claims is further set aside by a 1940 US Census record confirming Martino had a son named John whose age matches the individual identified by DiLeonardo: actor Johnny Martino, whose biography states he grew up in Brooklyn. The Godfather films are known for their popularity among mafia members and the public alike, with certain myths and realities linking real Cosa Nostra figures to the film's production, but "Paulie Gatto" has thus far been overlooked in these discussions. Perhaps the public should take special note of Johnny Martino's acting in the film: he knew the material far better than Brando, Pacino, and Caan.

Fiction is attractive to men within the mafia. There is ample evidence that pop culture's portrayal of the mafia has appealed to countless mafiosi going back to Sicily, where plays and other portrayals of the mafia have long been part of the local environment going back to the 1800s. In recent years, Buffalo Family underboss Domenico Violi, the Canada-based son of murdered Montreal Bonanno leader Paolo Violi, a Calabrian, was discovered with a signed photo of the Sopranos cast and Violi appears in photos socializing with other "mob" actors, a phenomenon evidenced among other Cosa Nostra members too numerous to include here. A well-known photo of the aforementioned Sonny Franzese shows him with a group of “mob” character actors, among them Frank Vincent and Vincent Pastore. Mafia members are drawn to their movie counterparts and the actors gravitate toward the mafiosi themselves, creating a mutual appreciation in which art imitates life and life in turn imitates art.

Michael DiLeonardo comes across less engaged by Hollywood's portrayals of Cosa Nostra than some of his peers. Former Gambino underboss Sammy Gravano, the man who presided over Michael's 1988 induction, has described how viewing the Godfather after its theatrical debut inspired him to commit himself further to life in the mafia. Gravano had no relatives in Cosa Nostra despite his Sicilian heritage, so a movie like the the Godfather may have helped fill in gaps left open by his non-mafia background. Another well-known Cosa Nostra commentator, former Colombo member Michael Franzese, the son of Sonny, hosts a weekly segment reviewing mafia movies, but the Franzeses were Neapolitans who first came into contact with the mafia in New York and their story is much different from that of the fictional Corleones. Like Michael DiLeonardo, the story of the Martinos is closer to the Godfather, with Gaetano Martino coming to New York as a Sicilian youth without his parents where he fell in with Cosa Nostra, much like the young Vito Corleone.

Michael DiLeonardo's more reserved interest in pop culture was likely influenced in part by his background, being surrounded since birth by Cosa Nostra figures with direct ties to its early history in both America and Sicily. As anyone with firsthand experience in a given subject knows, its portrayal by outsiders is sometimes irritating at worst and uninteresting at best. This is obviously not true for all mafia members and their relatives, who feel "seen" when their life is caricatured on screen, but DiLeonardo shows that not everyone in Cosa Nostra is as excited by their fictional counterparts when the reality is closer to home.

The Godfather's story of Sicilians from inland Palermo province climbing the ranks in early New York is a story that matches that of Michael DiLeonardo's own grandfather and great-grandfather. Michael's great-grandfather Antonino was inducted into the mafia in Bisacquino, a village neighboring Corleone, and his grandfather Jimmy was raised there before the two men immigrated to New York City and joined a local Cosa Nostra Family. The DiLeonardos’ close relationship to infamous Bisacquino boss Vito Cascio Ferro draws parallels to the Godfather as well. Cascio Ferro spent several years in America where he was a prominent mafia figure alongside capo dei capi Giuseppe Morello from Corleone and Morello's brother-in-law from Palermo citta, the early Gambino boss Ignazio Lupo. Jimmy DiLeonardo was a capodecina under Lupo's successor Toto D'Aquila, who also succeeded Morello as capo dei capi. Toto D’Aquila was Michael’s father Tony’s literal godfather and D'Aquila's descendants were Michael's mafia mentors. Their story may be more worthy of the title Godfather III than the movie’s actual script.

It should be observed that Gaetano Martino’s son Johnny is not the only actor named Martino in the Godfather, nor is he the most well-known one. Singer Al Martino played Vito Corleone’s crooning godson Johnny Fontane, but beyond appearing in the film together there is no connection between the two Martinos. Al Martino isn’t even a Martino, nor is he an Al. His true name is Jasper Cini and he grew up in Philadelphia with parents from Abruzzo on the Italian mainland. His true name and background are substantially different from Johnny Martino, the Sicilian-American from Brooklyn. Though Johnny too began his career as a singer, their different backgrounds also reflect the respective fictional characters they play, with Al Martino as the playboy singer and Johnny Martino a Corleone Family gangster.

Not all of Gaetano Martino’s masculine children were limited to the entertainment business when it came to “playing” a gangster. Michael DiLeonardo knew Gaetano’s son Nicky Martino to be active with the Gambino Family like his father, a matter of probability given he had eight sons total — a number that would have impressed Luca Brasi. The FBI carried a similarly named Dominick “Nicky” DeMartino as a made member of the Gambino Garofalo crew, though DeMartino’s age makes him too old to be a son of Gaetano and records confirm the slightly different surname under a father named Rosario, not Gaetano. Gaetano Martino did have a son name Dominick, named for his own father Domenico, though he also had a son named Nicholas who is likely the younger Martino known to DiLeonardo as “Nicky”. Gaetano testified that one of his sons supplied him with money for one of his 1940s Palermo trips but his sons Nicky and Johnny would have been too young to provide their father with financial assistance. He did have three older sons who reached adulthood by 1946, suggesting one of them helped.

After this article was initially published, a New York Post article was released that describes later contact between Johnny Martino and the Gambino Family. Martino was quoted in the article, recalling how after John Gotti became Family boss in the 1980s he reached out to Johnny through a Martino relative and was eager to meet the actor. At a warm meeting in a New York social club, Gotti and Johnny Martino offered future favors to one another and the Gambino boss requested that Martino go around the club shaking hands with the Family’s “skippers” (captains). Johnny Martino makes no reference to his father or his family history with the Gambino Family but this revelation is further indication of the Martinos’ deeper roots in the organization.

It is fitting that the old Jimmy DiLeonardo decina, with its ties back to the genesis of the modern Gambino Family, has a direct connection to the Godfather, the most popular and enduring portrayal of the mafia in American history. Fiction or not, the Godfather highlights certain realities of the early New York mafia, including its Sicilian origins, ties to inland Palermo, compaesani relations, and the role of blood and marital ties within the mafia network. While Sammy Gravano appears to have viewed the Godfather as an instructional course in aspects of mafia life that were foreign to him in Bensonhurst, Michael DiLeonardo was from the same neighborhood yet did not need to see the Godfather to understand how these deeper elements played a role in the life he lived. It would be interesting to hear Johnny Martino’s perspective given his background was similar to DiLeonardo’s, though Martino chose to portray a mafioso on screen opposed to the streets of Brooklyn where his father was a real Cosa Nostra member.

Compaesani, Multi-Generation Members, & Enduring Ties to Sicily

Gaetano "Tano Longo" Martino, who died in 1978, fits well within the compaesani make-up of the Lilo Garofalo crew based on his Palermo heritage. The DiLeonardos were a minority, having come from Bisacquino which sits deep inland near the border of Agrigento province and has more in common with rural mafia culture than the relative aristocracy of Palermo citta. Sicilian mafia pentito Giovanni Brusca of San Giuseppe Jato, which is closer to Palermo than Bisacquino, commented how men from Palermo called mafiosi from outlying villages “peasants” and this class tension provoked a half-cocked rivalry. Still, the DiLeonardos were from Palermo province and respected men like consigliere Joe N. Gallo and his friends the Rumores were Gambino members with heritage in Bisacquino, as were Gambino members in Baltimore who once reported to their own Palermitano captain.

Jimmy DiLeonardo had close ties to unknown Baltimore figures according to grandson Michael and a Bisacquinese man on the same ship as Jimmy DiLeonardo during a 1934 overseas trip shares a surname with one of the Gambino members in Baltimore. Joe N. Gallo was the Gambino Family’s official New York liaison to the Baltimore decina for decades, a role he carried until he became the Family consigliere. Their heritage in Bisacquino is the most likely reason for this connection given the influence of compaesani ties within the mafia network; Piddu Traina was close to the Philadelphia Family for identical reasons. It is significant that Bisacquino tended to produce Gambino members even in a city far from New York. Bisacquino, for reasons currently unknown to us, directed most of its mafiosi to the Gambino Family rather than the Corleone-rooted Genovese and Lucchese Families who were once dominated by men from villages surrounding Bisacquino.

As a member of the old Joe Riccobono crew, the Bisacquinese Gambino consigliere Joe N. Gallo was another regular at the East Village’s DeRobertis Pastry Shop and when Michael DiLeonardo was put “on record” as a young associate of the Gambino Family he was taken to meet with Gallo by his capodecina Lilo Garofalo. Garofalo explained to DiLeonardo how Joe N. Gallo descended from the same Sicilian village as Michael’s family, emphasizing the importance of these compaesani ties within the mafia subculture. Michael DiLeonardo knew of his family’s ties to Gallo, recalling how Joe attended his grandfather Jimmy’s wake years earlier and knew of a similar relationship with the Rumore brothers, two Bisacquinese Gambino members in the same decina as Joe N. Gallo. These compaesani relationships continue to be relevant in certain corners of the modern Gambino Family, particularly among the Palermitani.

Along with those already named, another example of Palermo heritage among the Garofalo crew's membership are the Melis. Giosue Meli was a contemporary of Jimmy DiLeonardo under Toto D’Aquila and Meli's sons, Angelo and Philip, would become members of this decina who died only recently, showing the crew's origins are not yet ancient history. Giosue himself died in 1973 and his mother was a Scarpulla, a surname found in the Scalise-Riccobono-Virzi clan that produced Gambino member Jack Scarpulla, suggesting potential interrelation between the two Palermitano crews. Of note is that one of Giosue Meli’s sons was a school bus driver later in life in addition to being a made member of the Gambino Family, a trait consistent with many mafia members in Sicily and the early US who carried out ordinary trades, including professions that outsiders would typically never associate with mafia membership.

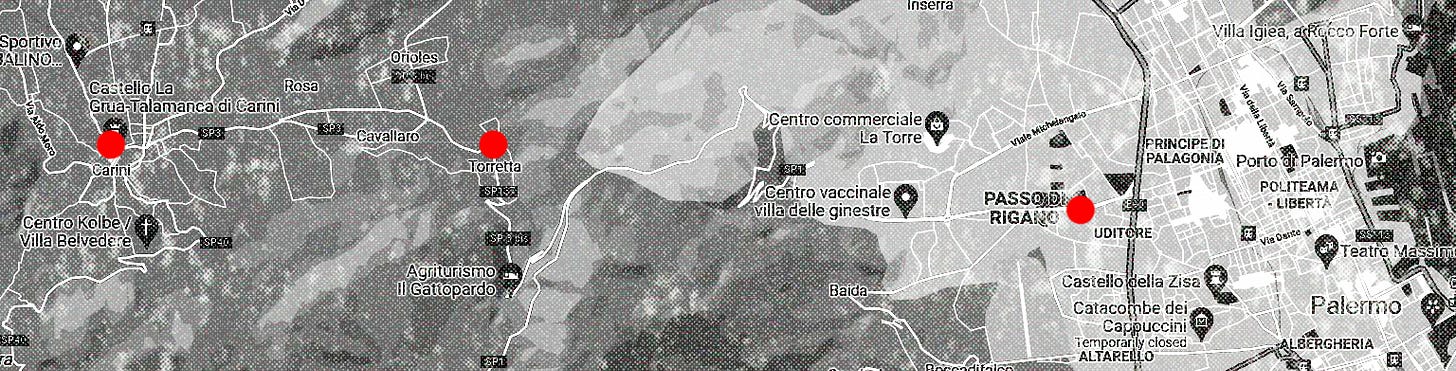

The heritage of most Garofalo crew members and their deep history with Salvatore D'Aquila show how this crew maintained a strong Palermo branch that lasted for generations, though it may be premature to say it has stopped growing entirely. Remnants of this crew today closely associate with the dominant Sicilian "zip" faction leading the Family, its members coming from Torretta and Passo di Rigano not far from Lilo Garofalo's birthplace of Carini. Most of the members and associates in this modern Sicilian faction come from neighborhoods in and around Palermo citta and the totality of the network’s membership includes members of various North American and Sicilian mafia organizations.

When the Gambino “zip” group’s leadership was incarcerated in the 1990s, their younger relatives temporarily reported to Garofalo’s successor Jackie D’Amico and Michael DiLeonardo was tasked with helping manage and mentor these up-and-coming Sicilian associates. Some of these men have been identified in recent years as made members of the Gambino Family who still maintain close ties with their relatives in the Torretta and Passo di Rigano Families, a fact confirmed in 2019 after the sweeping arrests of both New York and Palermo-based members from this clan.

A more recent Italian investigation in 2021 revealed how the Gambino leadership sent an emissary to Palermo for a meeting with Sicilian leaders from Torretta, a Family in the mafia district that produced the current Gambino “zip” faction. The American-born emissary had previously been a member of Jackie D’Amico’s decina and during this trip he helped arbitrate a dispute in Palermo that impacted internal politics within New York’s Sicilian faction. Among the issues he helped mediate was a disagreement over cattle ranching boundaries between two neighboring properties in Sicily, showing that mafia politics continue to include relatively mundane issues on an international scale.

Even seemingly minor events in Palermo can impact their Sicilian compaesani in New York and the reverse is likely true. Recent interactions appear minor, but the relationship is not fundamentally different from past events like the 1980s Sicilian mafia war, which directly impacted the Gambino-affiliated Palermitani and led to stateside murders. Gambino capodecina Antonino Inzerillo from Passo di Rigano was murdered in 1981 as a direct result of events in Palermo and his relatives in the Gambino Family were tasked with carrying out the grisly deed at the urging of Sicilian mafia leaders with the approval of boss Paul Castellano. The impact of transatlantic mafia politics is not new and there is evidence the Garofalo crew was closely involved in similar overseas affairs earlier in their history.

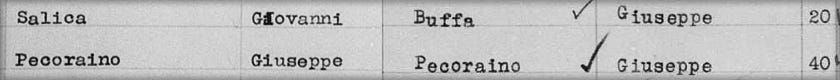

The Salicas were another family who provided two generations of Palermitano members in the Garofalo crew. Along with the DiLeonardos and Melis, they can be traced back to the D’Aquila era. Giovanni Salica was born in Palermo in 1883 and came to New York in 1902, arriving to a brother-in-law named Enrico Garofalo. Any degree of relation between Enrico and Lilo Garofalo is unknown, though Enrico Garofalo came from Palermo and his mother was a Salica in addition to marrying Giovanni Salica’s sister, indicating he was a cousin and marital relative. Salica lived in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, before moving to Gravesend, living one street over from Gaetano “Tano Longo” Martino. Martino’s house was likely visible from the backside of the Salica residence, as the homes were literally around the corner from one another on parallel streets.

Giovanni Salica’s son Louis would also become a Gambino member during the same era as fellow second-generation members Jerry D’Aquila, Paul Zaccaria, and the Meli brothers, showing how the decina continued to induct new members through the mafia’s traditional methods of recruitment. All of these second-generation members traced their heritage to Palermo. In addition to Giovanni Salica’s activities in New York, where he owned a Gravesend restaurant for a time, Salica may have also represented the Gambino Family during visits to his native Sicily.

Immigration records document how Giovanni Salica made several travels overseas during the 1910s and 1920s, one of at least two men from this group to do so. The crew’s capodecina Jimmy DiLeonardo, who wrote to Vito Cascio Ferro in 1909, also visited Sicily multiple times during this period, being accompanied by confirmed Cosa Nostra members. Multiple sources, including pentito Dr. Melchiorre Allegra, have confirmed that Salvatore D’Aquila sent emissaries to Sicily during the 1920s given the political impact events on both sides of the Atlantic had on the two respective branches of Cosa Nostra.

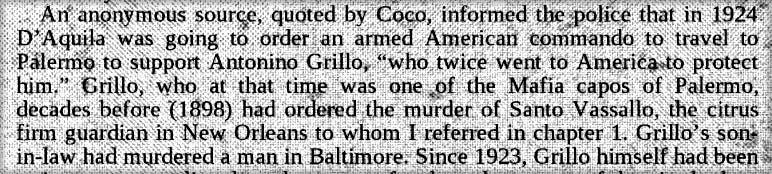

The 1920s were a volatile period for both New York and Palermo, with warring mafia factions murdering rival leaders and political intrigue forcing action from the American capo dei capi. Dr. Allegra commented specifically on internecine warfare that began ramping up in Palermo during the middle of the decade and stated that D’Aquila sent both personnel and resources to help resolve the matter. Another source cited by Sicilian mafia historian Salvatore Lupo stated that Salvatore D’Aquila sent an “armed American commando” to assist Palermo boss Antonino Grillo in 1924 and described Grillo’s involvement in multiple significant events involving America and Sicily spanning decades.

Jimmy DiLeonardo is recorded as visiting Sicily in 1924 with Buffalo member Paolo Palmeri, followed by Piddu Traina and Vincenzo Mangano traveling together in 1925. Though it is unlikely any of these leading figures served as an “armed American commando”, it is no coincidence three of D’Aquila’s top men, one of whom was accompanied by a Buffalo member, visited Sicily in 1924-1925 when tension was building before the outbreak of war in Palermo. Palmeri was the brother of Buffalo underboss Angelo Palmeri and Michael DiLeonardo was told Toto D’Aquila counted the Buffalo Family among his closest allies in the United States. Early Buffalo boss Joe DiCarlo Sr. was also related by marriage to Palermo boss Pasquale Enea, who previously lived in New York where he worked closely with Vito Cascio Ferro. A letter from capo dei capi Giuseppe Morello mentions the two men in tandem and describes them being involved in member inductions. Enea and Cascio Ferro continued this relationship after both men returned to live in Sicily.

We can infer from available information that Jimmy DiLeonardo, Paolo Palmeri, Piddu Traina, and Vincenzo Mangano made contact with Toto D’Aquila’s Palermo ally Antonino Grillo during their travels to Sicily in the mid-1920s. In addition to Grillo’s ties to the Gambino Family in New York, his son-in-law lived in Baltimore where he was allegedly involved in a murder. As noted earlier, Jimmy DiLeonardo had his own ties to Baltimore and the presence of a Grillo relative in the area shows both men may have had ties to an earlier incarnation of the Gambino Family’s Baltimore decina, which in later decades included Gambino members from both men’s respective hometowns of Bisacquino and Palermo, including a cousin of the Mangano brothers. Piddu Traina took a trip Sicily much earlier, too, traveling with Salvatore D’Aquila himself in 1910 and it’s highly likely Antonino Grillo was a factor in this visit as well given he visited New York that same year where he arrived to a local mafia figure.

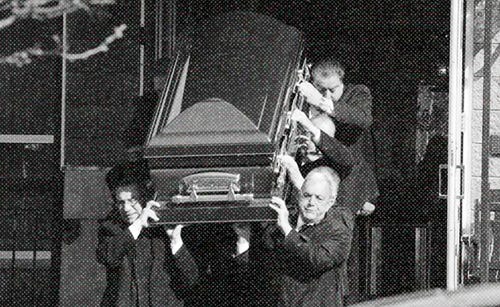

Jimmy DiLeonardo would again visit Sicily in 1929, this time with his son Tony and fellow Gambino member Andrea Torregrossa, a Brooklyn undertaker. A photo from the trip shows DiLeonardo and Torregrossa locked arm-in-arm with another unidentified man. Andrea Torregrossa came from Licata, Agrigento, where the majority of the Cleveland Family traced their roots, including several successive bosses in the 1920s. Michael DiLeonardo said his uncle John’s godfather was from Cleveland where he was murdered during an early mafia war, bringing to mind the murder of Tony DiLeonardo’s own godfather Toto D’Aquila.

A significant number of Licatese mafiosi in Cleveland were murdered in the late 1920s and early 1930s, increasing the likelihood that John DiLeonardo’s Cleveland padrino was from Licata like his father’s New York friend Andrea Torregrossa, though the sheer number of men from that town who were murdered in Cleveland makes it difficult to narrow down a candidate. John DiLeonardo was the same uncle described earlier who Paolo Palmeri hoped to incentivize to marry his daughter in the 1940s. Nicola Gentile, once a high-ranking Cleveland member before joining the Gambino Family, described how Paolo Palmeri spent time in Cleveland where he voiced concern over a local murder contract aimed at Licatese mafia leader Salvatore Todaro — Nicola Gentile served as godfather to Todaro’s daughter and successfully prevented his death, at least temporarily. Todaro would later become Cleveland boss and was killed for reasons unrelated to the earlier plot.

Along with Buffalo, Michael DiLeonardo was told Toto D’Aquila had a close relationship with Cleveland, which is further confirmed by Gentile who noted D’Aquila had a faction of loyalists and even a “secret agent” in the Cleveland Family under the guidance of boss Joe Lonardo, Torregrossa’s compaesano. A top capodecina under Lonardo identified by Nicola Gentile, Lorenzo Lupo, was a former Brooklyn resident who bridged the gap between Cleveland and Buffalo: Lupo was a cousin of the DiCarlos in Buffalo and came from their native Vallelunga. Like his allies from Licata, Lupo was murdered in the late 1920s. Probability suggests John DiLeonardo’s godfather was a Joe Lonardo loyalist given Jimmy DiLeonardo’s unique relationship with Toto D’Aquila and the Cleveland boss’s unwavering support of D’Aquila as capo dei capi. Lonardo was murdered in 1927, a year before D’Aquila’s own mafia-induced death, and Michael DiLeonardo suspects the Cleveland boss himself may have been his uncle’s godfather.

Along with documentation of their 1929 trip to Sicily, Jimmy DiLeonardo and Andrea Torregrossa appear together again in a wedding table photo decades later, the two men clearly enjoying the festive occasion in their old age. DiLeonardo’s nephew Joe Delmonico is seated at the same table alongside an unidentified older man believed by Michael to be a Gambino member. In addition to his shared hometown with Toto D’Aquila’s Cleveland allies, Andrea Torregrossa’s overseas trip with DiLeonardo indicates he may have been politically relevant himself. This is reinforced by Piddu Traina’s 1925 travel companion Vincenzo Mangano serving as godfather to one of Torregrossa’s children in the 1930s, Mangano being the Family boss at the time.

Andrea Torregrossa’s overseas affair with Jimmy and Tony DiLeonardo was one among many visits made by Torregrossa during these years. In addition to 1929, he traveled to Italy in 1925 and 1928. More significantly, he appears to have returned to his homeland a second time in late 1929 immediately following his arrival back in New York with the DiLeonardos that September, with records showing he again returned to New York in November 1929. These two back-to-back trips to Sicily on Torregrossa’s part in autumn of 1929, the first of which included Jimmy DiLeonardo, may be further indication Andrea Torregrossa had urgent affairs to attend to between the US and Sicily. He visited Italy again in 1948 and 1955, both times with his family.

Michael DiLeonardo believes Andrea Torregrossa was a one-time soldier in Jimmy DiLeonardo’s decina, though Torregrossa would report to another crew later in life, eventually being shelved under Carlo Gambino’s leadership for an infraction on the part of his son. His fall from grace did not prevent the Gambino Family and other New York groups from using his funeral parlor to wake deceased members and the large facility remains a fixture in Brooklyn today, still bearing the name “A.Torregrossa and Sons”.