Alabama, New Jersey, & the Agrigento Network

Examining the short-lived Birmingham Family and the Sicilian networks that connected it to the DeCavalcante and Gambino Families, among others.

Surprises still lurk in the history of the US mafia after decades of publicity and law enforcement scrutiny. The historic Cosa Nostra activity we're most familiar with often corresponds to organizations whose branches are the most exposed. New York City for example has given us extensive knowledge of its Cosa Nostra membership and activities, allowing us to work backward from later outgrowth to discover its roots.

Some of the smaller American Families remain mysterious, with researchers relying on fleeting anecdotes and superficial coverage via newspapers and occasional crime-specific prosecution that overlooks organizational details and internal politics. These sources are helpful but inherently limited, though we still have the essential research ingredient: we know these Families existed. If there is no evidence of an organization in a certain location it is near-impossible to identify its relevance to mafia history, though occasionally we receive confirmation of a Cosa Nostra presence in a previously unknown location.

There is little reason to believe any unknown Families came into existence after the 1930s and we can speak with a degree of confidence about which groups still existed after this period. The same is not necessarily true for Cosa Nostra's history prior to the formation of the Commission in 1931. FBI informants, government witnesses, and memoirs have given us the early American mafia's basic framework, though these accounts are generally the product of a later era and even sources who were around at the time are recalling old memories without the fresh details recent experience can provide. Still, surprising information can surface that changes our understanding of who and what existed where. One small footnote can shift our knowledge of Cosa Nostra's history and extend its network to locations we were previously unaware of.

This is true for Alabama, where a formal Cosa Nostra Family existed but faded from view before the public became fully aware of America's mafia landscape. Definitive information on Alabama’s exact hierarchy, membership, and range of operations is lost to time, but Alabama's presence in early mafia history is confirmed and we know the names of some individuals connected to the networks that fueled it. This article explores some of these disparate dots and attempts to connect them through our understanding of Cosa Nostra's larger patterns. The dots, though few, are not as distant as they might seem.

The article also veers into tangential information not directly related to the Birmingham area using what we know about the Sicilian compaesani (townsmen) groups that show up in Alabama in order to better contextualize the mafia environment that formed this organization. In addition to Alabama, individuals and Families discussed here will include the DeCavalcante, Gambino, Tampa, Chicago, and Kansas City Families, all of which were “in network” with Alabama to varying degrees especially as it relates to the mafia stronghold of Agrigento province. This article examines other mafiosi from the same Sicilian villages that surface in Alabama and the organizations they belonged to as well as the different geographic locations they ended up in. It’s all connected — most of it at least.

A Southern Revelation

The son of tenured New York boss and Commission member Joe Bonanno, Bill Bonanno was a leading Cosa Nostra member himself who fell from grace alongside his father in the mid-1960s. Bill became a secret FBI informant and later authored multiple books about his life in the mafia. His final memoir, The Last Testament of Bill Bonanno, was published in 2011 shortly after Bill passed away of natural causes. His co-author and confidant, lawyer Gary Abromovitz, assisted with the book's completion and naturally researchers have scoured each page for previously unpublished details from this unique Cosa Nostra scion.

While mainstream audiences may be attracted to Bill's tall tales about JFK and platitudes about Sicilian-American honor, hardcore followers of the subject are drawn to the names of previously unidentified members, insider explanations of mafia politics, and organizational data that keep the flames of mafia history alive and inform further research. Bill Bonanno's parting work was not without flaws or further questions, but it did generously deliver new leads to pursue.

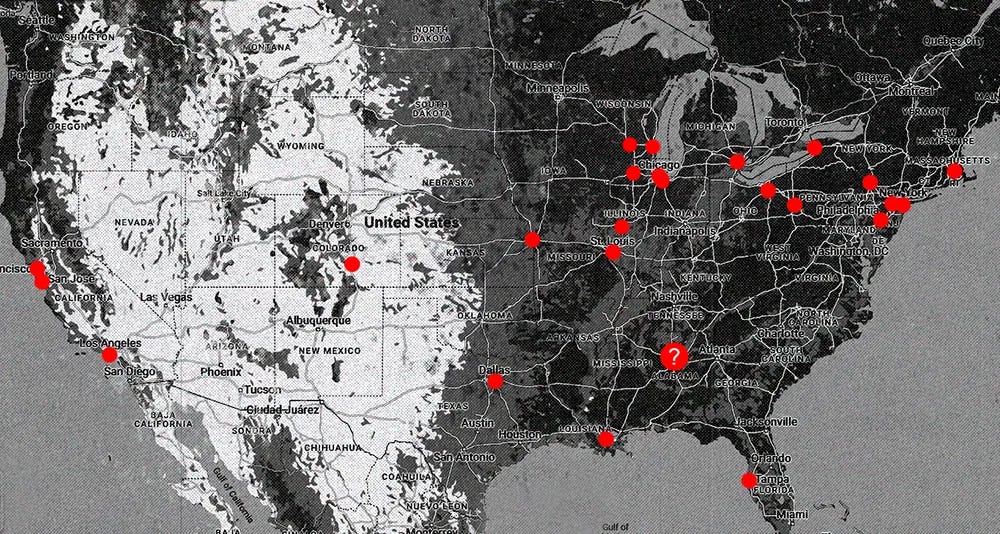

Elaborating on Cosa Nostra's evolution from a purely Sicilian phenomenon to an Italian-American “syndicate”, Bill recounted how the mafia crawled its way through the Southern United States first through New Orleans, soon establishing Families in other known outposts using networks established in Sicily. It’s known from other sources that the formation and maintenance of a Family is and was a highly formal process requiring that existing mafiosi receive official recognition from Cosa Nostra's national governing bodies, first under the capo dei capi and Gran Consiglio system, then later under its replacement the Commission. These mafia organizations were not arbitrary clusters of Italian criminals operating under a de facto hierarchy, but interlocking pieces of a time-honored system in which well-connected inviduals with membership in the same parent organization headed local branches using the same rules, protocol, and structure found in Sicily. Sicilian immigrants were drawn to certain regions of their new country through economic opportunity, kinship-informed chain migration, and in some cases affiliation with Cosa Nostra. The locations where Cosa Nostra ended up were not pre-planned but the formation of a new group was anything but arbitrary.

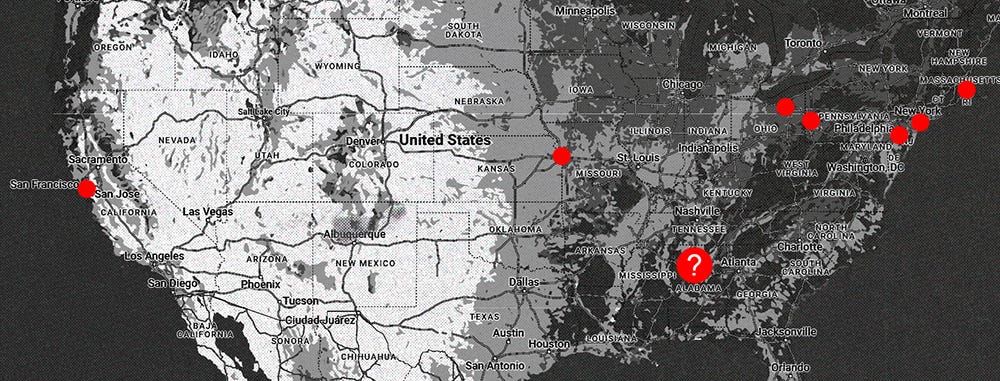

Bill Bonanno surprised readers in his Last Testament by identifying a previously unknown Family in an unlikely location: Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham was the only organization mentioned by Bill that was as-of-yet unheard of. In his discussion of how Cosa Nostra wound its way through the United States from the South upward, Bill first refers to New Orleans, St. Louis, and Kansas City as America's initial mafia organizations, followed by a number of other groups around the United States before he eventually cites a Birmingham-based Family that he asserts came into being around the middle of this dissemination process, with still other Families forming even later. Available evidence supports his statements about New Orleans and the Missouri Families, though the rest of the list appears random and some Families that are believed to have existed earlier are placed relatively late in his account.

What's important is not Bill Bonanno's understanding of which Family formed when, but that he includes Birmingham on a list otherwise populated by well-known organizations. Bill states too that many immigrants from Palermo settled in Alabama. This is not said in context with the mafia but in a segment about general Sicilian immigration patterns. He does elaborate more on this Birmingham Family a short time later, discussing the group only in its final hour.

According to Bill, the Birmingham Family was a withered and decrepit organization by the 1930s. The Family requested permission from the Commission to disband in the mid-1930s when the youngest member turned 80-years-old and the only recruitment prospect was 74, the Commission granting their request. Bill says the Commission assigned Lucchese boss Tom Gagliano to represent Birmingham's interests and by 1938 the last living member was deceased. This is the totality of his information on the Alabama mafia group.

Born in 1932 and inducted into his father's New York City organization in 1954 as a member and then capodecina of the Family's Arizona outpost, Bill Bonanno no doubt pulled his knowledge of this obscure group from older members. Though he does not cite a specific source, his father Joe Bonanno represented a Brooklyn-based Family from 1931 to 1964 and sat on the Commission for the first 33 years of its existence. Bill was a confidant of his father Joe and interviewed him extensively prior to the elder Bonanno's passing in 2002 at the age of 97.

Bill was also related through marriage to the Profaci clan, leaders of another Brooklyn Family whose elder members may have shared historical anecdotes with their younger in-law. Regardless of the details he shared or who provided him with this information, there is no reason to doubt Bill Bonanno's basic claim that a Family existed in Alabama. In fact, his revelation prompted further research that supports his general statement.

The Cosa Nostra network did extend to Birmingham and other areas of Alabama. Men from established Sicilian mafia strongholds settled in the area and others passed through during the unsettled early years of American mafia activity. Larger social, economic, and cultural factors that informed Cosa Nostra's development rested on shifting sand in the decades prior to the 1930s and our current notion of what a "mafia city" consisted of was still in its formative stages. Birmingham quietly came and went during this transition process and opens speculation as to whether similar examples in other US regions are quietly hiding somewhere in history. Barring revelations from men like Bill Bonanno, few of whom remain living, we are unlikely to confirm the existence of other formal groups but for now we can at least explore what's currently known about Alabama.

The Bigger Picture

Mafia history shows certain developmental trends that reinforce a general rule: Cosa Nostra was formed in Western Sicily, being comprised largely of kinship-based clans in specific villages, regions, and districts. The Sicilian mafia today is not identical to its ancestors in every way, though it still mirrors the basic politics, structure, and recruitment methods found among its ancestors and direct lineage to these early members and groups still exists in most if not all of the same locations on the island. As far back as the 1870s in Palermo and the 1880s in Favara, Agrigento, Italian investigations collected information that reveals similar structure, ranks, rituals, and many of the same rules applied in Sicily that we see today in America. The mentality found in the 19th century mafia is in many ways virtually identical to what exists today in this fundamentally conservative organization that manages to expand internationally with shocking flexibility without changing what it is.

When the organization transplanted itself to the United States it replicated itself accordingly, with colonies of interconnected compaesani interfacing with men from other nearby villages to form distinct groups that strengthened in number and gained influence via shared affiliation rather than division, with collaboration being a far more common theme than overt competition despite occasional warfare and violent enforcement practices. Some US cities and regions appear to have had multiple Families earlier in their existence, not unlike New York albeit smaller, with initial steps toward Americanization likely involving multiple compaesani-based Families joining together to form a single organization in a given US city or region. Evidence of this process exists in Philadelphia thanks to information from longtime member and FBI informant Harry Riccobene in addition to circumstantial evidence elsewhere.

Birmingham had Sicilian immigrants from multiple Western Sicilian provinces, though the specific villages in question tended to border one another geographically across provincial lines, bringing men together from a similar regional background with experience in the mining trade and agricultural labor. Though this process was not exclusive to the mafia, many early American mafia Families followed this pattern throughout the country, with the intersection of immigrants from nearby villages creating commonality that was no doubt enhanced by their shared status as Sicilian foreigners in a new land. There was incentive to band together as part of the Societa Onorata or Fratellanza, Sicilian mafia synonyms for what both America and Sicily now call Cosa Nostra, an essentially nameless organization that was universally understood by its members and affiliates regardless of the phrase used to invoke it.

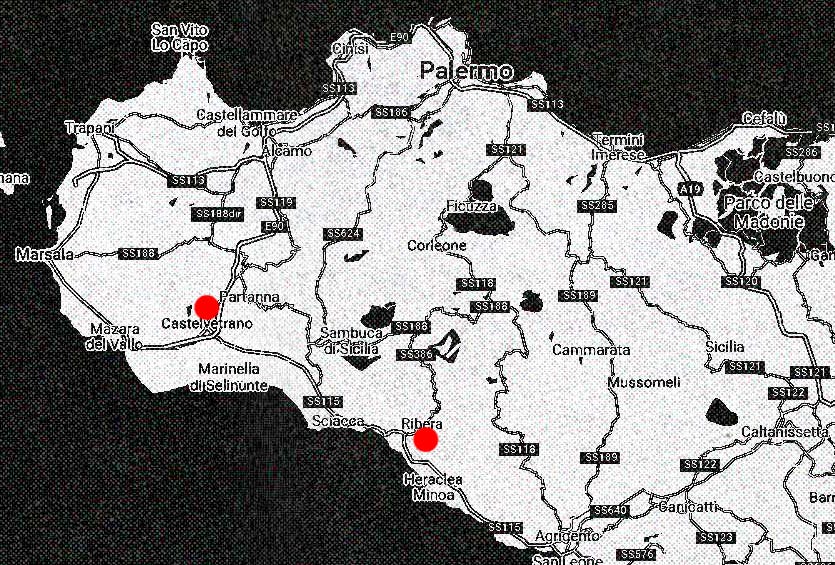

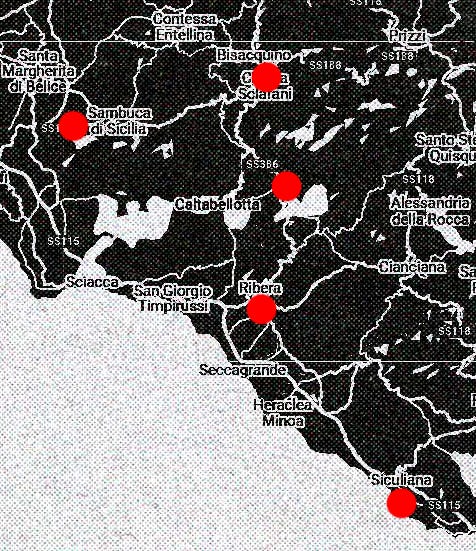

Villages that funneled likely mafiosi and their relatives into Alabama included Bisacquino, San Giuseppe Jato, Sutera, Campofranco, Casteltermini, Cianciana, Burgio, Ribera, Castelvetrano and others from the provincial borders connecting rural Palermo, Trapani, Agrigento, and Caltanissetta on the lower part of the island. Most of these towns are familiar to both Sicilian and American mafia researchers, being that they have a long history as mafia strongholds and produced well-known transatlantic names. It was perhaps inevitable that an undetermined number of Cosa Nostra figures would follow their compaesani to Alabama given the prevalence of mafia traditions in this network of villages.

Stepping away from the mafia, rural Sicilians in general were fundamental to the minority Italian population in Birmingham. Inland Sicily near the southern coast relied on mining and agricultural activity that provided locals with experience as farmers, laborers, and managers of sulfur and iron extraction, with Alabama's mining opportunities offering a natural fit for many of these Sicilian workers. As evidenced by the 1883 Sicilian Fratellanza investigation into a warring mafia Family in the Agrigento town of Favara, mining fell under the influence and even domination of local mafiosi, though generalizations should not be made: many Sicilian immigrants were simply looking for work and experience in the mining industry informed their overseas destinations with no evidence of criminal intent or corruption.

The extent to which the local Cosa Nostra organization infiltrated the mining trade in Sicilian-born Alabama residents' native villages is unknown, as is the level of influence the local Birmingham Family had over this industry in the United States, though cities like Pittston show the local mafia was capable of seizing a tight grip on mining given the right opportunity and circumstance. Farming also attracted rural Sicilians to Alabama and a clan of mafiosi existed in remote Russellville near the Mississippi border, including at least one man suspected of leadership over the Birmingham group despite living and working a significant distance from Birmingham during the period this Family is believed to have been most active.

Our general ignorance of the Birmingham mafia makes it impossible to theorize about their level of control, if any, over local trades and industries, as well as the sophistication of their organized crime activities. The local iron trade however was noted for having groups of Italian laborers referred to as "floating gangs" comprised of men who worked in the iron industry but had no specific duties and simply did whatever task was needed. One can imagine how the mafia might be able to manipulate these arrangements but for Cosa Nostra to take full advantage of the industry it would have required a degree of proprietorship like we see in the early Pittston Family, where mafia leaders owned mining companies and manipulated labor activism. Still, these industries were familiar to Sicilian mafiosi in their homeland and we often see American Cosa Nostra groups develop around these activities.

Despite the public's conception of a highly-concentrated urban mafia presiding over underworld activity on the gritty streets of New York and Chicago, the Sicilian mafia was and is largely a rural phenomenon. Sicily's economy is heavily agricultural, sustaining the bulk of its villages through the local land, with mafia membership shaped by this influence and in turn influencing it themselves. Along with organized cattle rustling, one of the earliest known rackets in Sicily involved the mafia's control over irrigation pipelines, with local mafiosi taxing farmers seeking to keep their crops watered.

Throughout its documented history the Sicilian mafia also inducted and promoted men with acceptable and even respectable positions in broader society, including doctors, businessmen, and politicians, though it balanced this upper class demographic with rugged farmers, bandits, thieves, and laborers who helped form a membership core that couldn't be typecast as it is today in America. These men were typically interrelated and all belonged to the same organization despite their differences. Through this diversity the mafia exerted its wide range of influence and capitalized on resources. Its members were united in secrecy, casting a malevolent silence designed to repel outsiders and maintain discipline among insiders.

Available evidence suggests the Sicilian mafia's diverse identity was carried to the early United States as well, with sources like Nicola Gentile describing doctors who worked alongside "gangsters" as formal members and even bosses of Cosa Nostra. Alabama was in certain ways an easy fit for highly-adaptable Sicilian mafiosi, especially members who descended from inland areas outside of Sicily's "aristocratic" coastal access points. Birmingham was not, however, as hospitable to Sicilian immigrants as other cities, where significant Little Italy colonies and everflowing immigrant clusters helped Italians retain their identity, which in some neighborhoods was inseparable from Cosa Nostra. Understanding how a Birmingham Family came to exist also requires an examination as to why it was not able to sustain itself as other Families did around the country. The reasons may not have been economic or criminal, but rather cultural.

Minority Report

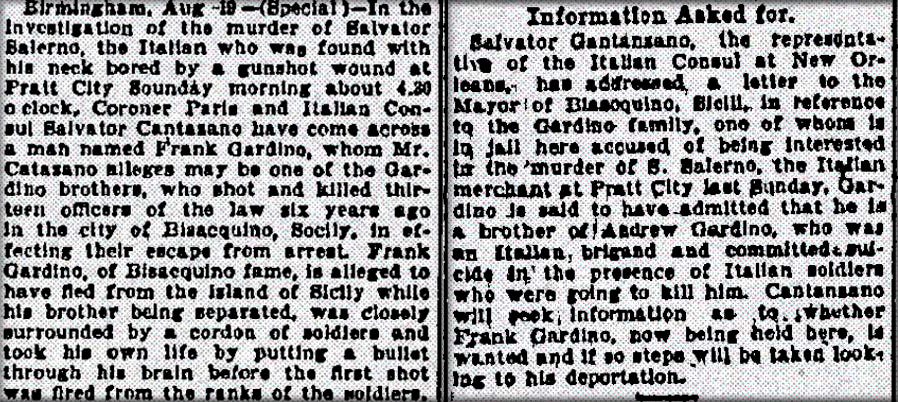

A report on the Italian history of Birmingham notes that 90% of the Italian immigrants in Birmingham were Sicilian and 30% of this number were from Bisacquino in southern Palermo province, a small village near Corleone and the provincial border with Agrigento that most notably produced the infamous transatlantic mafioso Vito Cascio Ferro as well as the multi-generation DiLeonardo clan of the Gambino Family, who were close friends of Cascio Ferro. This high percentage of Sicilians and specifically Bisacquinesi within an otherwise small Italian community is comparable to Tampa, Florida, where a similar majority of its Italian colony descended from Western Sicily, specifically a set of mafia-dominated villages neighboring one another in Agrigento.

An article on the history of Tampa’s Sicilian community states that the village of Santo Stefano Quisquina, which also surfaces in Birmingham, formed 60% of the Italian community, not even counting neighboring villages that also provided Tampa residents. These closely-connected Agrigento villages in Tampa reveal statistics comparable to Birmingham’s 90% Sicilian population within its own Italian community. The Tampa colony produced what is today known as the Trafficante Family and we can use this data to understand how Birmingham developed its own Family. The largest contributing factor behind the creation of a recognized Cosa Nostra Family was not a large pan-Italian community but a highly-concentrated Western Sicilian population where the mafia subculture was known and its “laws” were practiced.

In addition to Bisacquino, other villages noted in the report as producing significant numbers of Birmingham Sicilians were Campofranco, Cefalu, and Sutera. Immigrants from Grotte, Agrigento, were specifically named in the report as arriving to Birmingham to work in the sulfur mines, a trade many of the area's labor-ready Sicilians had experience in. Grotte is just over 8.5 miles from Favara, where the Fratellanza investigation identified absolute mafia dominance over the mining industry in the early 1880s. Immigrants from Bisacquino had history as miners as well but the village’s name ominously means “Father of the Knife,” derived from the Arabic Abu-seckin, a reference to the town’s history of commercially producing knives using goat horns as handles.

Before 1898, most Sicilians came to Birmingham from New Orleans while after 1898 they came via New York, with Ellis Island becoming the primary port of entry for immigrants, Italians being no exception. Some of the known mafiosi in Alabama arrived in New York following this shift, though the report on Birmingham Italians states this change in entry point had no immediate impact on chain migration, which continued through New York as it had in New Orleans, the presence of compaesani and relatives in Alabama being a bigger attracting force than port of entry. Supporting this is that some mafia-connected figures who surface in Alabama came to the area through both New Orleans and New York, though the pre-1898 arrangement in Louisiana made immigration to Alabama easier and over time these changes did greatly limit Alabama’s Sicilian and Italian growth along with restrictive changes in immigration policy.

The Italian identity and its core traditions were said to be difficult to maintain in Birmingham because the Italian colonies were spread out, contrasting with the concentrated Little Italy communities found in larger cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. Though the report describes this impediment in context with Italian culture in general, it likely contributed to the Alabama Family's inability to survive into the modern era. Mafia Families tended to form in tight-knit Sicilian colonies but thrived and survived in pan-Italian communities that provided them with social infrastructure, deeper recruitment pools, and diverse economic and criminal opportunities, allowing mafia organizations to build on themselves from one generation to the next. These larger urban Families also recruited mainland Italian criminals some of whom once had their own analogous organizations.

The report on Birmingham Italians states that Alabama's various Sicilian colonies unsurprisingly held feasts for the patron saints of the following villages: Bisacquino, Campofranco, and San Giuseppe Jato, these feasts being a hallmark of Italian ethnic identity that brought the community together. These early generations of immigrants in Birmingham were also said to consider themselves "Sicilitani", "Bisacquinari", and "Campofrancesi" [sic] rather than "Italiani", hometown signifiers that informed the clannish Sicilians' identities far more than their relatively recent inclusion into the broader pan-Italian identities developing in both Italy and the United States.

These hometown-based descriptions that various compaesani used for themselves factored heavily into mafia politics, with numerous sources throughout the United States even in later decades referring to factionalism within Cosa Nostra Families based on hometown and region. These terms were famously used during the Castellammarese War in New York City in 1930 through 1931, the name of the war itself drawing from the name for Sicilians from the town of Castellammare del Golfo in Trapani province. Nicola Gentile even described the opposing faction as the Sciacchitani, a reference to the Agrigento village of Sciacca. These regional identities formed the basis for the mafia's sub-networks and patterns of association. Birds of a feather flocked together and these flocks were primarily compaesani, many of them interrelated.

Nicola Gentile, a senior representative of an extensive Agrigento mafia network active between the early 1900s and 1930s, wrote an invaluable memoir and obsessively refers to the hometown and ethnic identities of Cosa Nostra members he knew in the United States. When Gentile transferred membership to the Gambino Family in the early 1930s he was designated by boss Vincenzo Mangano, a Palermitano, as his sostituto (substitute) tasked with mediating affairs within the Family's insular Agrigento faction in Manhattan which comprised multiple Family crews. The men from Agrigento were given a great deal of autonomy in part due to a compaesano identity that was distinct from that of the Palermitani who ran the Family they all formally belonged to. Mafia compaesani groups maintained both comradery and rivalry within their own element, with the Birmingham Italian report showing this was not exclusive to Cosa Nostra but a core part of sicilianismo.

The report states that Alabama's Sicilian immigrants strongly preferred compaesani from their home villages and there was a "chauvanism" expressed with the word campanilismo, translated in the report as "my village is better than yours." This was short-lived, though, as the wider culture of Alabama that surrounded these Alabama colonies forced Sicilians to adopt a more general Italian-American identity that prevented individual paesani identities from influencing the core Italian community long-term like we see in other US cities.

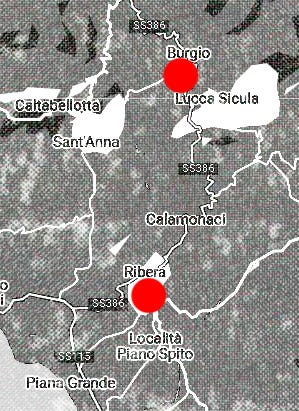

In the New Jersey DeCavalcante Family for example, which was largely comprised of immigrants from Ribera and nearby Agrigento villages, the group still echoes aspects of this campanilismo, having actively recruited men from Ribera into the modern era. The DeCavalcantes have maintained an insular organization that interacts with nearby New York and includes members there but the Family remains quiet and sequestered, much like Birmingham's historic Sicilian colonies. The DeCavalcante Family in fact had mafia compaesani in Alabama who lived in Russellville and Birmingham, these Riberesi appearing to serve an important role in the organization that will be elaborated on later, though Russellville's remote location shows them to be just as aloof as their peers in New Jersey. Interestingly, the Riberesi are not mentioned in the report on Birmingham Italians referenced in this section, though other documentation proves their existence.

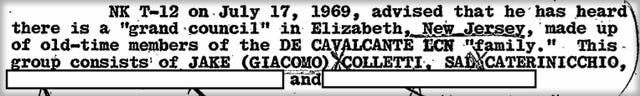

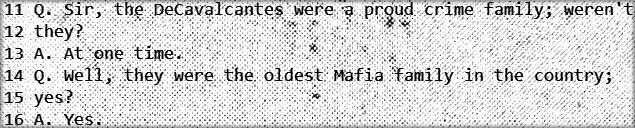

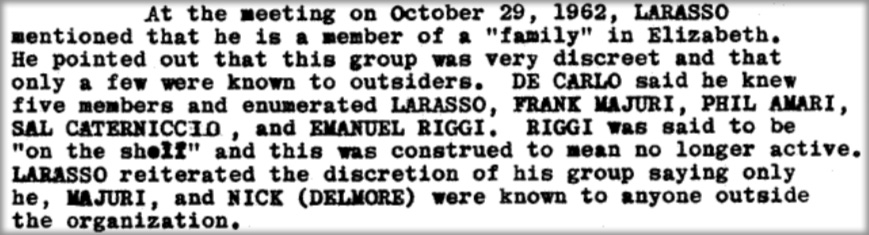

We can use our knowledge of the DeCavalcante Family to understand these mafiosi from Ribera who ended up in Alabama and this article will also explore the history of the DeCavalcante Family as it is inseparable from the Alabama Riberesi. The DeCavalcantes did have criminal activities but when the FBI first learned of them as a distinct New York-New Jersey Family in the 1960s, in part through clandestine recordings made in boss Sam Rizzo DeCavalcante’s office (while Western Sicilian, DeCavalcante was not Riberese), it was revealed that much of the membership was comprised of older men from shadowy Agrigento.

Most of these Agrigentino DeCavalcante members in New Jersey as well as New York were laborers for the Family-controlled Local 394 union and the primary perk of mafia membership in Elizabeth was preferential treatment in the Local. While not lawful adherents of the American legal system, these were not master criminals and some of them engaged in no crime at all beyond occasional labor bullying. Due to the tendency for certain compaesani groups to share a similar mindset, we can use the DeCavalcantes to better understand Riberese mafiosi in Alabama.

Though it sits in a different province, Ribera is geographically close to prominent Birmingham Sicilian hometowns like Bisacquino and Campofranco. Former Gambino capodecina Michael DiLeonardo states that his grandfather Vincenzo, an early Gambino capodecina himself from Bisacquino, was close to men from Ribera in New York City due to this regional proximity, so Ribera is hardly out of place among other Sicilian villages like Bisacquino that produced heavy concentrations of Alabama residents.

Between 1900 and 1910 the Italian population in Birmingham more than tripled. Newspaper reports from early in the century reveal intensive efforts to bring Italian laborers to Birmingham and other southern cities. However, immigration reform in 1917 greatly reduced Italian immigration and likely dealt a major blow to mafia growth in the area. Along with a cultural climate that limited Sicilian and for that matter Italian identity, it makes sense that the Alabama Family disbanded less than two decades after immigration was stunted by these legal changes. In contrast with Birmingham, other American cities received a major influx of Sicilian and Italian immigrants during the 1920s and even into later decades, these waves of immigration naturally including Sicilian Cosa Nostra members and others molded by the mafia subculture.

There was no central leader of the Birmingham Italian community according to the report on Birmingham’s historic Italians, this role often referred to as a padrone, but the following men were said to carry out select duties in the community: Egidio Sabatini was the arrival contact for most Italians in Birmingham and helped them find housing; food importer Paul Tuscano helped immigrants with legal problems; GA Firpo was a New Orleans Italian Embassy Vice-Consul based in Birmingham who helped represent immigrants within local government and facilitated communication with the Italian government; Jake Guercio, a barber, led local Italian mutual-aid societies and was a contact with the "business elite"; and physicians Louis Cocciola, Louis Botta, PT Falletta, and dentist BF Sapienza were other influential community figures.

Guercio was from Cefalu, Falletta from Campofranco, and Sapienza from Gratteri but the other leaders’ names do not appear to be Sicilian. There is no reason to suspect the three Sicilians of mafia association but other cities in the United States show it was not uncommon for ostensibly legitimate figures in the Sicilian community to be members and leaders of the local Cosa Nostra organization, exerting themselves more within their own small communities where the mafia system was well-understood. Many compaesani-based fraternal societies and clubs carried Cosa Nostra members and leaders as administrators and chairmen, the DeCavalcante Family’s Ribera Club in Elizabeth being a well-known example but only one of many.

Prejudice was prevalent in Birmingham. In 1905, Birmingham congressman Oscar Underwood spoke out against Italians because they were not of the "Aryan race." He stated that Italians, Spaniards, Greeks, and Assyrians had mixed blood from Asia and Africa, therefore Anglo-Saxons should not intermingle with them. There was significant discrimination against Italians by local Anglo-Saxons that dominated Birmingham and Underwood proposed strict immigration reform that limited "non-Aryans" in the years to come and specifically targeted Italians, while Scandinavians, Germans, and Brits were free to arrive in larger numbers.

The Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham reportedly targeted Italians because of their darker complexion, this taking place between the years 1915 and 1930. The Klan also severely cracked down on bootleggers during Prohibition, which began earlier in Birmingham than the rest of the country. While the public often mistakes bootlegging for the genesis of American Cosa Nostra, it nonetheless provided most US Families with an infusion of wealth and power, these groups utilizing their existing national networks and organizational structure to rapidly gain influence over the illegal alcohol industry. Sicilian mafiosi expanded their network during this period to include a wider range of Italians and even non-Italians who engaged in bootlegging and other emerging criminal activities, a luxury less affordable to mafiosi in oppressive Birmingham.

San Diego-based Los Angeles member and prolific FBI informant Frank Bompensiero told the FBI he was sent to Tampa by his “incensed” boss Jack Dragna around 1933 to assist the Florida organization in their efforts to combat the Ku Klux Klan. He stated that an armed group of Los Angeles members ambushed Klan members who were descending on a Tampa member’s house and exposed the perpetrators’ identities, local community figures among them. He said this Los Angeles mafia element remained in Tampa for two years to continue protecting local Cosa Nostra members from the Klan.

The Los Angeles and Tampa Families have few known connections and were formed by different compaesani groups on opposite sides of the country, but as Frank Bompensiero’s account shows, the mafia was deeply interconnected and invested in one another’s well-being in different locations. A lack of insight into the Alabama Family makes it impossible to know if they were offered similar support from national Cosa Nostra groups in resisting the Klan's violent bigotry, but the Klan's reported policing of local bootlegging activities indicates that mafiosi were significantly handicapped by these outside forces in the Birmingham area if indeed they sought to engage in illegal alcohol distribution like their national peers. The Ku Klux Klan and police alike even accosted Italians and other immigrants for ignoring the Sabbath on Sundays, showing that it was not just illegal activity the Klan targeted but all customs not in line with the Anglo-Saxon majority.

Though the report on Birmingham's Italian history sheds no direct light on its Cosa Nostra organization, indeed the report makes no reference to the mafia at all, the information presented in the report greatly informs our understanding of its local mafia group. With 90% of its Italian population descending from Sicily, particularly regions dense with Cosa Nostra activity dating back to the 1800s, it is unsurprising that a formal mafia group formed there, just as it is equally unsurprising that its lifespan was cut short by the factors discussed here.

The Birmingham Family's inability to sustain itself was undoubtedly influenced by crackdowns on Italian immigration in the late 1910s, which had a dramatic impact on Birmingham's Italian colonies during the 1920s when the rest of the US mafia got a new wave of recruits from Sicily. The Italian community was also decentralized and spread out in several different colonies and the Klan's harsh opposition to bootlegging and foreign ethnicities prevented Birmingham Italians from thriving as Italian communities did elsewhere. Anglo-Saxon discrimination toward Italians in local government and social life forced Italians to assimilate and abandon much of their independent identity or leave the area.

We don't know if Bill Bonanno's word-of-mouth reference to the mid-1930s disbandment of Birmingham is the exact time of the Family’s dissolution, but the known history of Italians in Birmingham fits perfectly with the idea of an early mafia Family who couldn't maintain their organization in this environment. We lack information on the formative years of the Family, too, making it difficult to understand the group's exact genesis, nor do we know how potent the group was earlier in its history. There is evidence New Orleans was a fully-functioning mafia city by the 1860s, with cities like St. Louis, Tampa, Dallas, Chicago, and San Francisco showing similar trends before the turn of the 20th century, making the Alabama Family perhaps older than we know given the presence of Western Sicilian immigrants by the 1890s

Thus far this article has attempted to contextualize the local environment of Birmingham as it relates to Alabama's immigrant Italian colonies, providing substance in the form of Sicilian hometowns with an enduring mafia pedigree and circumstances that could and did facilitate the existence of a recognized Family even if this arrangement was unsustainable. These circumstantial factors are of marginal use without specific people, though. Bill Bonanno did not provide any names connected to the Birmingham group despite his apparent knowledge of one member's advanced age, but fortunately other material has assisted in identifying possible members, associates, and perhaps even one of the Family's leaders.

Pasquale Amari & Riberese Mafia Clans

A remote colony of immigrants from Ribera in Russellville, Alabama, 110 miles from Birmingham, interestingly has given us names and connections that have helped us understand who was involved with the mafia in Alabama. One of these men had a surname and hometown familiar to Cosa Nostra researchers and his involvement in a mafia-like crime in his native Sicily prior to entering the United States is further indication that this man was a mafioso. His story also reflects the kinship ties that are so essential to Cosa Nostra’s existence.

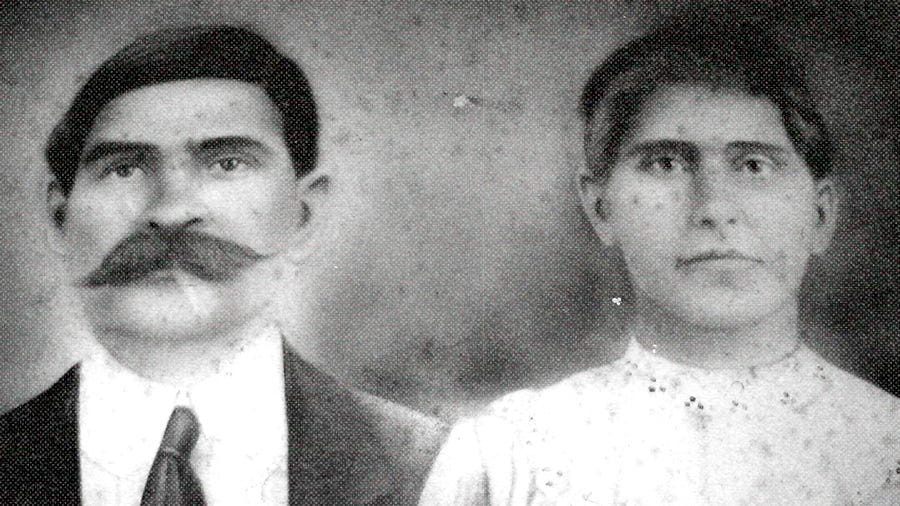

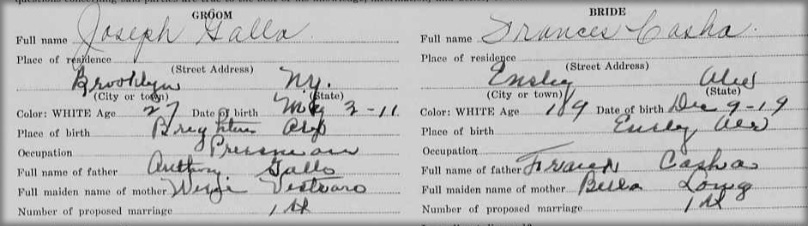

Pasquale Amari was born in Ribera in 1865 to Giovanni Amari and Giuseppa Schittone, residents of the same village that produced Filippo “Phil” Amari, the first confirmed DeCavalcante Family rappresentante in New Jersey who served through the mid-1950s, as well as Phil's relative Gioacchino “Jake” Amari, who served as underboss and acting boss of the same Family decades later in the 1990s. Phil Amari’s father Giuseppe was the brother of Jake Amari’s grandfather, named Gioacchino like him. Though a blood relation can’t be confirmed at present, Pasquale was related to this branch at least through marriage which will be explored in further detail later.

Both of the New Jersey Amaris maintained close ties to Ribera and traveled back there while residing in the United States, Phil Amari even being accompanied by Riberese mafiosi from Chicago during a 1948 visit and Jake Amari reportedly meeting with Ribera Family members during at least one of his own visits. Another native of Ribera named Nicolo Amari was identified by authorities as a Sicilian mafia figure living in Florida into the 1990s where he associated with members of the Tampa and DeCavalcante Families. The Amari name is said to be among the first known surnames established in the village of Ribera, though it took on various forms including Amaro, D’Amari, and D’Amaro.

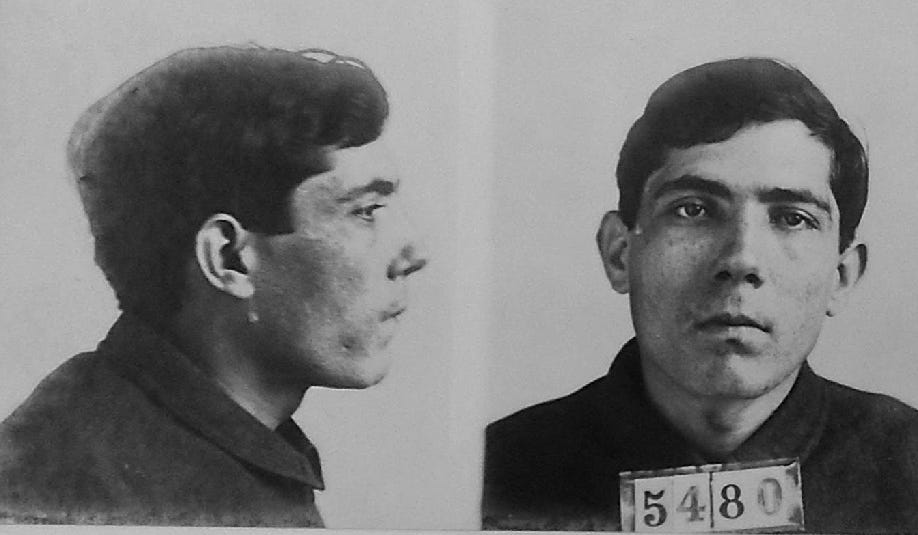

Between 1893 and 1903, Pasquale Amari served approximately ten years in prison after having been convicted of murder in Ribera. Amari stabbed a man to death at a card game in a Ribera cafe in connection with a gambling debt. The murder appeared to be pre-meditated though available information does not elaborate on the full context of the killing beyond it being related to gambling and money. The alleged motivation for the murder suggests Pasquale Amari either had a stake in the gambling game as a participant or organizer, or perhaps he loaned the victim money. Amari was described as having a shortened index finger, the cause of the injury unknown but it occurred prior to his incarceration.

Pasquale Amari's wife, ten years his junior and only fifteen when they married, was Giuseppa Schittone, whose mother was a Giacobbe. The couple was married in 1890, around three years prior to his murder conviction and prison sentence. Schittone was likely a cousin of Amari, as Amari's mother shared the name Giuseppa Schittone. While an exact relation to the Schittone-Giacobbes can't be determined, the Giacobbe surname connects to Riberese mafiosi in the US and Sicily much as the Amari name does.

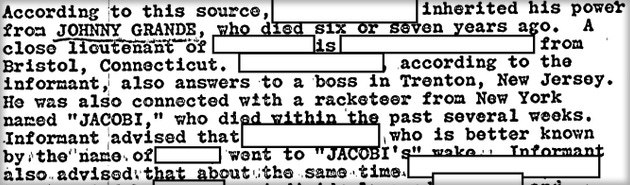

Lorenzo Giacobbe was identified as an early DeCavalcante capodecina by former New York-based captain-turned-cooperator Anthony Rotondo, with Lorenzo's son Joseph also gaining membership and serving as an acting capodecina when Rotondo was active. These Giacobbes lived in Manhattan, Queens, and Connecticut during different periods, all locations linked to the DeCavalcante Family in addition to the group's eventual headquarters in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Two relatives of the DeCavalcante Giacobbes, Emanuele Giacobbe and his son Leonardo, were identified as made members in Ribera, with investigations in the United States indicating Leonardo Giacobbe transferred his membership to the DeCavalcantes upon moving to New Jersey, a formal practice not entirely uncommon between the two intertwined transatlantic Families who share common lineage. Historic mafia journeyman Nicola Gentile transferred membership between Cosa Nostra organizations in the United States and Agrigento himself generations earlier. Anthony Rotondo recalled how several made members of both the DeCavalcante and Ribera Families transferred their membership back and forth depending on where they lived.

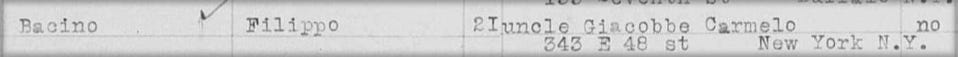

The DeCavalcante Giacobbes were also relatives of Chicago Family member Filippo “Phil” Bacino, who belonged to a powerful faction of Riberese mafiosi in Illinois who were closely linked to the DeCavalcantes. Bacino's marital uncle and arrival contact when he arrived to New York City from Ribera in 1923 was Carmelo Giacobbe, the elder brother and uncle of Lorenzo and Joseph Giacobbe, respectively. Phil Bacino spent only a brief time in New York before moving to Chicago and eventually nearby Calumet City but he retained a close relationship to DeCavalcante boss Phil Amari, with Bacino and two other Riberese mafiosi from Chicago participating in the New Jersey Ribera Club's orphanage committee with Amari and other DeCavalcante members, including Bacino’s relative Lorenzo Giacobbe. Phil Bacino’s son would also marry a girl from Elizabeth he met while attending the wedding of DeCavalcante leader Frank Majuri’s daughter in New Jersey.

The aforementioned orphange committee, formed in 1947, was comprised almost entirely of confirmed Cosa Nostra members in New Jersey, New York, and Chicago, with the few remaining names being obscure older figures who, if these patterns are any indication, were possible DeCavalcante members themselves. Mafia figures on the committee from New Jersey included boss Phil Amari and his eventual successor Nick Delmore, as well as Joseph Sferra, Giacomo Colletti, Salvatore Caterinicchio, Emanuele Riggi, and Frank Majuri, who traced his heritage to Corleone but would marry a woman from Ribera. The committee’s New York element included Lorenzo Giacobbe, Pietro Galletta, and Joseph Lolordo. Emanuele Sortino, who also sat on the committee, was not a known DeCavalcante member but his family was part of the Ribera Family in Sicily.

This ostensibly legitimate arrangement reflects not only mafia membership but also significant stature in the local Cosa Nostra organization. Amari and Delmore would be Family rappresentanti, as noted, while Majuri became an underboss and Sferra, Colletti, Giacobbe, and Lolordo all held the rank of capodecina at various points. Caterinicchio was described by a later source as a member of the Family’s advisory council and Emanuele Riggi was himself a powerful member whose son John became a Family boss.

This Ribera Club committee directly reflects the DeCavalcante Family’s hierarchy, with lesser-known committee members Charles Coniglio, Domenico Renda, Vincenzo Carlino, and Joseph Matina being names from Ribera or surrounding areas who were undeniably amenable to Cosa Nostra given the other names among them. A later incarnation of the same committee shows the same tendency and included Family boss Sam Rizzo DeCavalcante, Sam’s underboss and eventual successor John Riggi, consigliere Stefano Vitabile, capodecina Paolo Farina, former underboss and capodecina Louis LaRasso, and member Joseph Colletti (son of Giacomo, previous committee member), who may have been a capodecina for a time as well.

Another committee member during the Rizzo DeCavalcante era was Gioacchino “Jack” Miceli. Miceli was not a formal part of Cosa Nostra but his first cousin Alfonso Miceli was a made member in Ribera and Jack Miceli was president of the Ribera Club itself, also being married to a Riggi. His obituary states he helped 75 different people immigrate to the United States, no doubt many of them from Ribera. Jack Miceli was buried at the Corsentino Funeral Home in Elizabeth, a facility operated by second-generation DeCavalcante member Carl Corsentino who is entirely legitimate and even served as Vice President of the local Board of Education.

An unknown name on the later committee was Joseph Parlapiano, his surname heavily linked to Agrigento. Nicola Gentile’s capodecina in the New York Gambino Family at one time was another man named Giuseppe Parlapiano from Sciacca. One name on the committee that can be discounted from mafia membership rolls entirely is the non-Italian Mike Kleinberg, though Kleinberg was a key Family associate who held an important managerial position with the DeCavalcante-controlled Local 394, showing him to be far from an ordinary “civilian”. The committee’s goals were charitable but it was indistinguishable from the DeCavalcante Family’s own organizational structure and it was represented by the most important mafiosi in the American branch of the Riberese mafia network.

The committee was organized because the Ribera Club had sponsored the construction of an orphanage in their native Ribera, which the club continued to hold annual fundraisers for during the next 50 years. Former Family associate Frank Scarabino noted that members of the Ribera Family traveled to the United States for these fundraising events even in recent decades, showing the Ribera orphanage to be a joint effort between Riberese mafiosi in the US and Sicily consistently since its formation. The Sicily-based brother of DeCavalcante soldier Pietro Galletta, Francesco, was the mayor of Ribera in the 1960s and was referenced in a newspaper account discussing the Elizabeth group’s involvement with the orphanage, Pietro sitting on the Ribera Club’s committee himself.

The Chicago representatives on the committee reveal how compaesani relationships among Riberese mafiosi extended to other US cities. Like most of the New York and New Jersey committee members, all three of the Illinois names were Cosa Nostra figures who descended from Ribera: Phil Bacino, Vincenzo “Jim” DeGeorge (true name DiGiorgi), and Nicola Diana. Bacino and Diana even traveled to Sicily with Phil Amari in 1948 for the orphanage’s grand opening. The much older Pasquale Amari who would reside in Alabama was related via marriage to Nicola Diana of Chicago.

Pasquale Amari’s sister Rosaria married Francesco Diana in Ribera and their son Calogero would move to Chicago, where Ribera Club committee member Nicola Diana resided. Calogero Diana’s father Francesco was the brother of Nicola’s father Vincenzo, making the two men first cousins. Pasquale Amari’s nephew Calogero lived on the same block as leading Riberese members of the Chicago Family, including DeGeorge, Pasquale Lolordo (whose brother Joseph also sat on the Ribera Club committee), and Vincenzo “James” D’Angelo. Lolordo became boss of the Chicago Family in 1928 and was subsequently murdered in early 1929, while DeGeorge was a capodecina who became involved in an internal conflict within the Family in the 1940s that led to his demotion and semi-retirement to Wisconsin. D’Angelo was murdered in 1944.

Nicola Diana was allegedly no stranger to violence. He was arrested in Chicago in 1940 after nine years of hiding in plain sight and charged with murdering a local police officer in 1931, his car having been connected to the killing. At the time he was arrested, Diana was in the company of Emanuele Cammarata, a New Jersey resident and native of Villabate in Palermo who spent time in Chicago. Both men were in the olive oil business, an industry Cammarata shared with his cousin Joe Profaci, by this time rappresentante of a New York Family. Cammarata and Profaci, along with Diana’s Chicago compaesani Pasquale Lolordo and Phil Bacino, had been arrested together in 1928 at a famed Cleveland meeting attended by top Cosa Nostra members around the country.

A witness to the police officer’s 1931 murder was unable to identify Nicola Diana and he escaped prosecution. By 1947 he was part of the Chicago contingent of the New Jersey Ribera Club’s orphanage committee with Phil Bacino as well as Jim DeGeorge, though DeGeorge, who by this time may have fallen from grace in Chicago, did not accompany Amari, Bacino, and Diana to Ribera the following year for the grand opening of the Ribera orphanage. Ostensibly the owner of a Calumet City pizzeria, Phil Bacino had more in common with Nicola Diana than their heritage alone: Bacino was charged with the murder of a former police officer in 1935 though he too escaped proper punishment.

By the time of his voyage to Ribera with Phil Bacino and DeCavalcante boss Phil Amari, Nicola Diana was living in Phoenix, Arizona, a destination for Chicago mafia figures. Amari’s brother Vincenzo would also settle in Arizona much later after leaving New Jersey, Vincenzo Amari coming to America after killing a man named Antonio Russo in Ribera in late 1924. Along with his ties to the New Jersey Amaris, Nicola Diana is a confirmed marital relative of Birmingham’s Pasquale Amari through his first cousin Calogero, Amari’s blood nephew, and Pasquale shared a marital relation to the Giacobbe surname along with Bacino, these men’s lives complementing one another in many ways.

That Pasquale Amari stabbed a man to death in Ribera in the early 1890s parallels Phil’s brother Vincenzo Amari committing a murder himself in their hometown over 30 years later. Nicola Diana was accused of killing a police officer in Chicago in the 1930s, as was Phil Bacino, showing a violent streak among the Riberesi in the United States as well as Sicily, where this temperament apparently originated. Like his relatives the Giacobbes' overseas relatives in the Ribera Family, Phil Bacino's brother Luciano was identified as a senior mafioso in Ribera by Italian authorities during the 1940s and 1950s. There is high probablity that the Amari, Diana, Giacobbe, and Bacino families trace their roots to older generations of Ribera Family mafiosi, Pasquale Amari being part of this elder group.

In 1912, around nine years after Pasquale Amari’s release from prison, the 47-year-old ex-convict entered the United States where he listed his arrival contact as Giuseppe Mule, sometimes spelled Muli, the son of his sister who was living in New York City. Accompanying Amari was a Riberese woman returning from a visit to Ribera, Anna Miceli, who previously lived in Tampa. Miceli was at this time heading to Bayonne, New Jersey. The longtime Ribera Club president in Elizabeth described earlier was Jack Miceli from Ribera, the cousin of a Ribera Family mafioso and a member of the club’s orphanage committee that included much of the DeCavalcante Family leadership.

Anna Miceli’s mother in Ribera was a Triolo, the same surname as Chicago mafioso Phil Bacino’s mother. Further recurrence of these names comes from Bacino’s paternal grandmother, a Miceli from nearby Burgio, with the Bacino family later moving to Ribera. It is through the Triolo name that Phil Bacino was related to the DeCavalcante Giacobbes, with Bacino’s own NYC arrival contact a decade later, Carmelo Giacobbe, married to his mother’s sister, a Triolo. A relative named Triolo was also among Bacino’s criminal associates in Illinois and Indiana, as were other Bacinos from Burgio, one of whom told the FBI Phil was a distant relative.

Like the woman’s name who accompanied Pasquale Amari to America, DeCavalcante boss Phil Amari also had a maternal aunt named Anna Miceli who married his father’s brother, named Filippo like him. There is a discrepancy in ages between this Anna Miceli and the one who accompanied Pasquale Amari to America, indicating this was a different woman or there was a transcription error when the age of the woman traveling with Pasquale Amari was recorded.

The Miceli family Phil Amari’s aunt descended from lived in Ribera for multiple generations, making a relation to Phil Bacino’s Miceli relatives from Burgio indirect if indeed there is a relation but the Burgio tie-in brings to mind early St. Louis boss Pasquale Miceli, a native of Burgio who lived in Chicago in the 1920s alongside Bacino. A possible early Chicago boss was Pietro Catalanotto from Villafranca Sicula, directly between Ribera and Burgio, though he was murdered in the mid-1910s before these men arrived to the city. Another common surname between Phil Bacino and Pasquale Amari is Mule, a name related to Bacino’s father Giovanni’s family again in Burgio.

A future Riberese Chicago mafia boss was living in New York City at the time Pasquale Amari arrived there in 1912: Pasquale Lolordo, the future neighbor of Amari’s nephew Calogero Diana in Chicago prior to Lolordo’s 1929 murder. Lolordo was married to the daughter of a Domenico Mule, who also lived in New York at the time and shares his surname with the nephew Pasquale Amari arrived to in NYC, Giuseppe Mule. Tying these names tighter together is Lolordo's close association with Phil Bacino, the two men arrested together at the 1928 Cleveland meeting alongside Joe Profaci of New York and his cousin Emanuele “Nello” Cammarata of New Jersey, the latter noted for being with Nicola Diana during the latter’s 1940 arrest in Chicago.

Lolordo’s title as Chicago rappresentante at the time makes his attendance easily understood, though the presence of Lolordo and Bacino together may have had more significance when considering the importance of compaesani ties in mafia politics. Other Chicago area figures also attended, including high-level figures from the town of Cinisi, suggesting there was representation from different Sicilian factions. Pasquale Lolordo likely headed the national Riberese network at this time given his stature in Chicago.

Pasquale Lolordo's in-laws the Mules descended from Caltabellotta, a comune near Ribera and Burgio that produced DeCavalcante members, including New Jersey-based capodecina Paolo Farina and two men suspected by the FBI of being members of the Family’s Manhattan-Queens faction, the Marsala brothers. Pasquale Amari’s 1912 arrival to the United States included a Giuliano Farina from Caltabellotta on the same ship. Farina was later connected to the Marsala brothers, his paesani with the DeCavalcante Family, and he was likely a relative of Paolo, having a brother of the same name. As with Ribera and Burgio, intermarriage between the villages of Ribera and Caltabellotta was not uncommon and the same surnames surface in both villages.

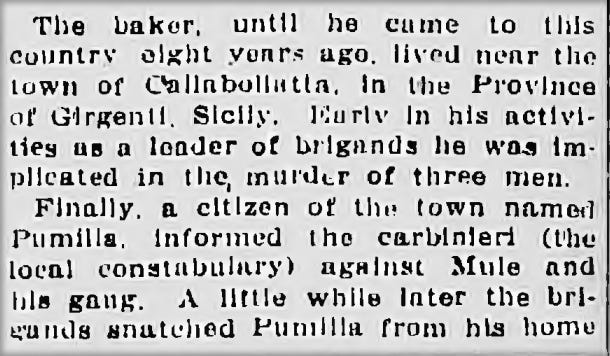

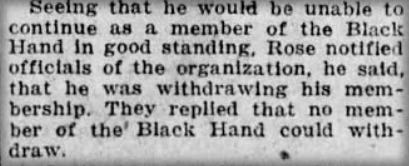

An early mafia figure from Caltabellotta named Pellegrino Mule also lived in Manhattan in the early 20th century, being linked to so-called "Black Hand" extortion in the city circa 1908. This Mule was wanted by Italian authorities for three murders in Sicily, having killed one of these men in Sciacca, a prominent village on the coast near Caltabellotta and Ribera that produced a large amount of the Gambino Family’s Agrigento faction, many of which had ties to the same Manhattan neighborhoods Mule frequented.

Pellegrino Mule, a baker by trade, was identified as the leader of a group of terroristic bandits in Sicily prior to his arrival in New York City with implications he was a mafia leader in the hills of Caltabellotta before absconding to New York. His heritage and stature would have placed him in the networks discussed here and his surname connects to Pasquale Amari and Pasquale Lolordo, coming from the same miniscule village as Lolordo’s in-laws who share his name. One of the men he allegedly killed in Sicily was decapitated, showing Mule to be capable of far more than baking bread. Interestingly too, his nephew was named Trafficante like the well-known Tampa leaders who came from another Western Agrigento village, Cianciana, though there is no apparent connection between them.

Along with Paquale Lolordo marrying a Mule from Caltabellotta, his brother Joseph married a woman named Cascio in Los Angeles, her father Vito coming from Lucca Sicula, a village between Ribera and Burgio that produced Pueblo Family leaders along with Burgio. An obscure New Jersey-based Bonanno Family capodecina, Giuseppe Colletti, was from Lucca Sicula, as was his cousin Vincenzo “Jim” Colletti, an ex-Bonanno member who moved to Colorado and became the local rappresentante. This Bonanno group, which included Angelo Salvo with heritage in Alessandria della Rocca, had close relationships to the DeCavalcantes and Giuseppe Colletti’s brother-in-law and successor Angelo Caruso, from Leonforte in Enna, was among Frank Rizzo DeCavalcante’s intimate friends.

Pasquale’s brother Joseph Lolordo eventually became a DeCavalcante capodecina in Queens, having left Chicago after his brother Pasquale’s 1929 murder. Joseph Lolordo’s in-laws the Cascios lived in Linden, New Jersey, prior to living in Los Angeles where the Lolordo-Cascio marriage took place, Linden being the home of many DeCavalcante members who belonged to the nearby Elizabeth organization. Phil Amari would himself move to Los Angeles where he died of natural causes in 1963 after being deposed as DeCavalcante boss, his son-in-law being Los Angeles member Salvatore Pinelli, whose father Tony had been an Indiana-based capodecina of the Chicago Family before transferring to Los Angeles. Tony Pinelli was from Calascibetta in Enna province, the same region that produced Amari’s successor Nick Delmore, but he was related to the Riberesi on two fronts, another son marrying the daughter of fellow Chicago capodecina and Ribera Club committee member Jim DeGeorge.

By 1930, Joseph Lolordo and his wife were living with his widowed sister-in-law, Pasquale’s wife, and her father Domenico Mule in Queens. Phil Bacino’s relatives the Giacobbes would live in this same part of Queens and maintained a close relationship to Joseph Lolordo. Despite living in New York City, both the Giacobbes and Lolordo were closely involved with Local 394 in Elizabeth and Joe Lolordo’s in-laws’ previous residence in Linden shows them to be part of these circles as well.

Though Bacino was not in the United States when Pasquale Amari arrived to his nephew in New York, nor was Bacino’s uncle Carmelo Giacobbe, Carmelo’s brother Lorenzo of the future DeCavalcante Family was living in Lower Manhattan in 1911. By 1917, Lorenzo Giacobbe had moved to Hartford, Connecticut.

Eventually a DeCavalcante Family underboss, Joseph LaSelva, as well as capodecina Mickey Puglia were identified as Connecticut-based members of the organization, an unintuitive arrangement that would be virtually impossible to identify without inside sources. The Family’s Connecticut leaders were not Sicilian, but the earlier presence of Lorenzo Giacobbe in the state, where a small Ribera colony existed at the time, potentially helped lay a DeCavalcante foundation in the area that eventually included local recruits who took on important positions. An FBI informant in the 1960s seemed to refer to the recently deceased Giacobbe in a report about Connecticut activities, further supporting this theory.

As with Connecticut, the contemporary Ribera network was planting its seeds in other unlikely locations in the early 20th century. Following his 1912 arrival in NYC, Pasquale Amari soon traveled to Alabama where his sister and brother-in-law Giuseppe Caterinicchia were already living as farmers. Amari's family would arrive approximately one year after he settled in Alabama and Pasquale joined his brother-in-law in the agriculture trade, soon starting his own farm in Russellville.

Living in Alabama alongside Pasquale Amari at this time was Giuseppa Amari Mangiaracina, the sister of DeCavalcante boss Phil Amari’s father Giuseppe and therefore not only Phil’s aunt but also the great-aunt of Jake Amari, being the sister as well of Jake’s namesake grandfather Gioacchino. Giuseppa’s husband Giuseppe Mangiaracina descended not from Ribera but Castelvetrano in Trapani. The presence of Phil Amari’s aunt in Alabama with Pasquale Amari, specifically in tiny Russellville, provides evidence of a relationship between the two Amari branches but the relationship grew even tighter in Russellville.

The son of Giuseppa Amari and Giuseppe Mangiaracina, Vincenzo, married Pasquale Amari’s daughter Mary in Birmingham in 1928, meaning Phil Amari’s first cousin was married to Pasquale Amari’s daughter. This union confirms that Pasquale Amari’s grandchildren would become blood relatives of Phil and Jake Amari through their paternal grandmother, though a relation between the two Amari families likely already existed based on the marriage alone and common chain migration patterns that brought both Amari branches from Ribera to the same obscure farming community in Alabama.

A descendant of Pasquale Amari described how the small number of families in Ribera and extensive intermarriage between them over generations made virtually everyone with the same surname a cousin to varying degrees. This is not lost on modern mafia members from Ribera. Trenton-based DeCavalcante member Girolamo Guarraggi’s funeral service was aired online, his brother commenting how Girolamo was obsessed with Sicilian hometowns and when meeting other immigrants the mafioso could tell them who all of their relatives are without having previously met them. Girolamo Guarraggi was another ostensibly legitimate DeCavalcante member who had been part of the same New Jersey Board of Education that once carried DeCavalcante member Carl Corsentino as its president.

These connections would have been even more familiar to early generations of immigrants like Pasquale and Phil Amari, whose relation has been substantiated via marriage even though the exact blood relation of Pasquale Amari’s father Giovanni to Phil’s ancestors is currently unknown. Phil Amari himself would arrive to America in 1921, the same year Carmelo Giacobbe came to New York from Ribera and two years before Phil Bacino arrived to his uncle Giacobbe. Carmelo Giacobbe, born in 1874, has never been identified as a made member of the DeCavalcantes like his brother Lorenzo and nephew Joseph, his advanced age obscuring him from later sources, but the additional involvement of his other nephew Phil Bacino as a member of the Chicago Family places Carmelo deep within Riberese mafia circles even though his own role remains a mystery.

Carmelo Giacobbe is the eldest known figure from his clan to live in the United States and was only nine years younger than Pasquale Amari, whose wife’s mother was a Giacobbe. Though Carmelo was living in Ribera prior to his 1921 arrival to New York City, he may have visited New York many years earlier, a man with his name and age arriving in 1906 to a cousin named LaSala, another surname that produced a Riberese DeCavalcante member. If this is the same Carmelo Giacobbe, his stay was not permanent and he returned to Ribera for a period. There is a high degree of probability that Carmelo Giacobbe and Pasquale Amari were contemporaries in the Ribera Family before both men arrived in America.

What is known of Pasquale Amari’s wife’s maternal heritage does not reveal an obvious connection to Carmelo Giacobbe despite her mother being a Giacobbe. Indication of common lineage does come through the name of Pasquale Amari’s wife’s grandfather, Emanuele Giacobbe. Carmelo and Lorenzo Giacobbe had a brother named Emanuele and as noted earlier, Lorenzo and his son Joe had another relative made into the Ribera Family named Emanuele Giacobbe. Sicilian naming traditions utilize the same given names from generation to generation and though a connection appears distant these shared names could suggest common lineage between Pasquale Amari’s wife and the DeCavalcante Giacobbes.

Pasquale Amari's connections invoke the names of other Cosa Nostra figures from Ribera, this winding genealogical road and its many detours into New York, New Jersey, and Chicago showing confirmed and possible relationships between many different mafia figures in Ribera and throughout the United States. The murder of a man at a gambling game in Amari’s hometown is further evidence of his participation in mafia-like activity. However, it is not Pasquale Amari who was the most significant Ribera-born mafia figure in Alabama, rather it appears this status belonged to his brother-in-law Giuseppe Caterinicchia. Caterinicchia’s ties to Cosa Nostra figures are less incidental and he can be directly linked to two of the most important mafia leaders in America during the 1920s.

Giuseppe Caterinicchia & the National Mafia Network

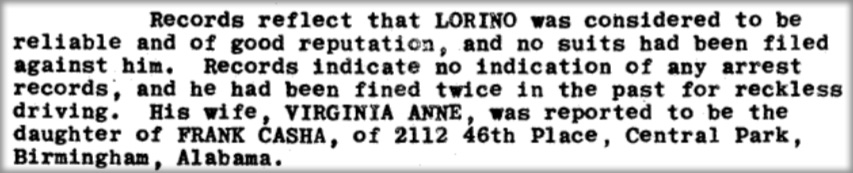

Giuseppe Caterinicchia was born in 1861 and descended from Ribera like his brother-in-law Pasquale Amari, having married Pasquale’s sister Antonia in Sicily. Arriving to the United States via New Orleans in 1897 or 1898 (records state both), many years before Amari's own arrival, Caterinicchia would settle in Alabama where he established a farm in remote Russellville. Caterinicchia maintained a presence in Birmingham, with Giuseppe and many of the Caterinicchia-Amari clan relatives eventually living in and around the city after leaving Russellville. Investigation into other Cosa Nostra figures also reveals that Giuseppe Caterinicchia received mail from high-ranking mafiosi at a Birmingham address.

A 1923 Secret Service record shows mail communication between Giuseppe Caterinicchia and Boston-based New England boss Gaspare Messina, who would later become interrim capo dei capi in 1930 after Joe Masseria was deposed and eventually killed the following year. Messina sent Caterinicchia $77.50 to a Birmingham address, a sum that would be worth over $1162 today. While not a small amount of money, neither is the total massive within the scope of underworld activity.

The nature of this payment is unknown, though it indicates a shared business interest or that Messina was otherwise lending support to Caterinicchia. Cross-country partnerships between members were formed around counterfeiting in the early part of the century, with mafiosi using these same networks for bootlegging during the 1920s when Messina sent the money to Caterinicchia, though mafia leaders were also known to utilize the same relationships for legitimate business partnerships or to lend each other general assistance. These networks weren’t formed by specific activities, rather Cosa Nostra used its existing networks for whatever activity they were currently engaged in, be it legitimate, criminal, or simply social.

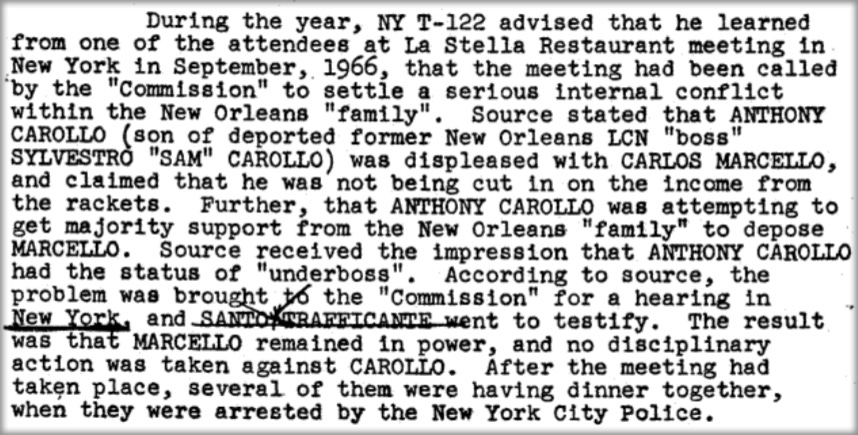

Gaspare Messina descended from Salemi, an inland village in Trapani province just over 50 miles from Giuseppe Caterinicchia's hometown of Ribera. Messina had no known presence in Alabama, nor did Caterinicchia have established ties to New England, but the mafia network was intricate and even without close association mafia members communicated via letter, attended national Assemblea Generale meetings in various locations, and knew one another by reputation if not personal acquaintance. Nicola Gentile, who was well-acquainted with Gaspare Messina, also provides a common link between Messina and Caterinicchia.

Nicola Gentile was well-traveled in both America and Sicily. A native of Siculiana, a town in Agrigento with close ties to Ribera, Gentile was inducted into Cosa Nostra in the United States, transferring membership into various US Families through his nomadic movements . He also transferred in and out of Sicilian Families during extended stays in his homeland. Though born in Siculiana, Gentile was involved with the Families in nearby Porto Empedocle and Realmonte while residing in Sicily and in his memoir he confirms his transfer to the Porto Empedocle Family for a period. He also had close ties to Ribera, noting that his brother-in-law was in Ribera during one of these Sicilian trips. Nicola Gentile's close friend Antonino Cucuzzella was also a Riberese figure who can be connected to a family of mafiosi affiliated with the DeCavalcante and Chicago Families.

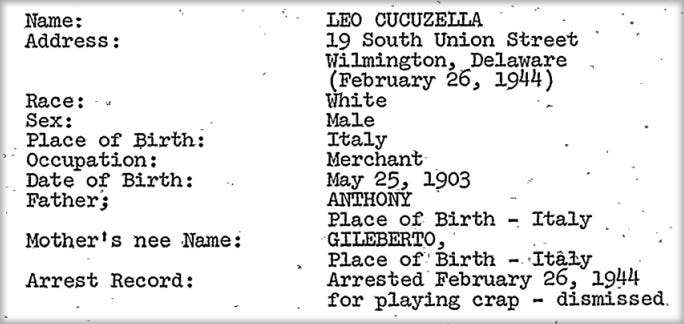

Though Gentile's references to his friend Cucuzzella are brief, focusing only on an ill-fated trip to Quebec during World War I where Cucuzzella had relatives, genealogical records and later FBI investigation revealed the Cucuzzellas had ties to prominent Riberese mafia figures in New York and Chicago. The Cucuzzellas were extended relatives of the Lolordos, specifically Chicago Family boss Pasquale and his brother Joseph, the Queens DeCavalcante capodecina described earlier.

Antonino Cucuzzella lived in New York City and his son Calogero "Leo" Cucuzzella would settle in Philadelphia then Delaware where he was once arrested on gambling charges. The FBI's investigation into Joseph Lolordo revealed that Leo Cucuzzella maintained contact with his cousin in New York until the end of Leo’s life. It's possible both Cucuzzellas were associated with the DeCavalcante Family, a group known for its widespread but tightknit membership that included members in Elizabeth, Trenton, multiple New York City boroughs, Marlboro, Connecticut, and even New Orleans. The presence of Leo Cucuzzella in Delaware could expand that range slightly. Trenton DeCavalcante member Girolamo Guarraggi also has relatives in Delaware as well as Canada like the Cucuzzellas.

Heritage and kinship often tied the DeCavalcantes together more than geographic proximity. Like Antonino Cucuzzella, Joseph Lolordo kept ties to their mutual relatives in the large Montreal Agrigentini community, an element in Canada that bleeds in with the Montreal Bonanno crew. These Canadian Bonanno figures came from Cattolica Eraclea and Siculiana, forming their own extensive compaesani clans of deep interrelation that produced Cosa Nostra members in multiple countries. A recent Italian investigation recorded the Sciacca Family boss stating that the Ribera Family currently has a gambling machine partnership in Canada with mafiosi from Cattolica Eraclea.

Nicola Gentile's connection to Giuseppe Caterinicchia does not just come peripherally from relationships to Caterinicchia's compaesani in other cities like Antonino Cucuzzella and his relatives the Lolordos — Gentile and Caterinicchia can be directly connected. Arrested in the late 1930s for his role in a narcotics trafficking network between New York and New Orleans, Gentile's address book was obtained by authorities and showed a "who's who" of the mafia's Agrigento network. Mafia-affiliated names and addresses across the United States filled the pages of Nicola Gentile's address book and there was even a lone listing in Birmingham: "Joe Catarinicchia [sic], R.F.D. Box 298, Birmingham, Ala."

Though Gentile does not mention traveling to Alabama in his memoir nor does he acknowledge any awareness of the Birmingham group, he was a member of the Gran Consiglio, a spiritual predecessor of the Commission that mediated national disputes for what he termed the Societa Onorata, what members now call Cosa Nostra. His duties often pertained to the national Agrigento network that he himself was instrumental in preserving and expanding. The Gran Consiglio naturally included representatives of these different networks, perhaps more appropriately called “sub-networks” given they all fed into the larger Cosa Nostra network. It is logical Nicola Gentile’s role familiarized him with Giuseppe Caterinicchia given the latter was a mafioso from Ribera.

Gentile was a mafia socialite, attending banquets around the country and showing intense comradery with his underworld peers regardless of location. Gaspare Messina even held a banquet in Nicola Gentile’s honor during an early 1920s Boston visit, though pressing matters didn’t allow Gentile to attend. Comically, the banquet took place anyway and Gentile was told by a friend how the Boston boss gave a toast in the absent Gentile’s honor. Gentile and Messina were also involved in high-level machinations during the Castellammarese War close to a decade later, both men connected to different national factions despite their friendship, though the two of them served primarily as mediators rather than stoking the flames of war. Messina, as noted, was the interim capo dei capi while Gentile sat on a national peace committee alongside top rappresentanti.

Nicola Gentile states in his memoir that everything he did in life was connected to Cosa Nostra. The appearance of Caterinicchia's Birmingham mailing address in Gentile's address book is hardly mysterious in this regard given Giuseppe Caterinicchia’s hometown and their mutual connection to Gentile’s friend Gaspare Messina. While there is a degree of probability that Nicola Gentile personally met Giuseppe Caterinicchia during his extensive travels, especially when he served as Kansas City boss in the early 1920s, Gentile later described how he communicated via letter with prominent mafiosi he had yet to meet in person, with long-distance social networking directly informing his travels, residences, and even formal membership.

Gentile for example noted that he had been in communication with Pittsburgh boss Gregorio Conti via letter, Conti being a native of Comitini in Agrigento, and though the two men had yet to meet, Gregorio Conti knew of Gentile's reputation and invited him to Pittsburgh, an offer Gentile accepted. Nicola Gentile moved to Pittsburgh and subsequently transferred membership to the Western Pennsylvania organization under Conti and became one of its leading members.

It is easy to be skeptical of Nicola Gentile’s pride in his own underworld reputation, his memoir a constant stream of Gentile’s accomplishments in mediation as well as mafia enforcement. He doesn’t hesitate to describe the way other high-ranking members fawned over him. A significant amount of the information he provided does correspond to available records, however, and though there are occasional discrepencies and mistakes, most of his recollections don’t suggest deliberate dishonesty. One reputable source does support Gentile’s description of himself as an esteemed mediator: Francesco “Frank” Coppola, a similar high-ranking journeyman within his own Partinico sub-network. Deported in the 1940s and often the target of narcotics investigations in Italy, an aging Coppola provided an interview with an Italian journalist in the 1970s in which he confirmed Nicola Gentile was a skilled mafia counselor. Coppola told the journalist how Gentile’s advice should have been consulted more often by younger non-traditionalists like Charlie Luciano, Albert Anastasia, and Al Capone.

Further objective evidence of Nicola Gentile’s stature comes through his relationship with the powerful Charlie Luciano, the two men closely associating after both had returned to Italy by the mid-1940s. While residing in his native Sicily, Gentile told authorities that a name relevant to this article, Phil Amari, even traveled to Italy where he met with Luciano. Like Alabama, though, he never once acknowledges the DeCavalcante Family’s existence despite his confirmed association with Riberese men like Antonino Cucuzzella and apparently Giuseppe Caterinicchia.

Though it’s unknown if Nicola Gentile actually corresponded with Giuseppe Caterinicchia through the Birmingham address found in his possession, Gentile's postal communication with Pittsburgh boss Gregorio Conti, tenure as a ranking member in multiple American and Sicilian Families, and involvement with the Gran Consiglio show that he had a direct line to leaders in virtually every city. Family rappresentanti in the early American mafia were not as insulated as later bosses who now seek to protect themselves from increased law enforcement scrutiny and media attention but still, a member is not allowed to contact a boss blindly and though in these early years the boss was receptive to meeting a broader range of members, it still required that he receive approval from his superiors and that the rappresentante be notified in advance.

Outsiders at the time were quite dense in perceiving the true nature of these relationships and mafiosi could operate within their own society with relative freedom so long as they followed rules and protocol. Protocol was not designed to limit them, but to maintain discipline within the international system of shadow governance. There are examples of rank-and-file members being allowed direct contact with another Family’s rappresentante when traveling and moving to different cities, though Gentile was not one of these “ordinary” members and often held administrative positions in addition to his involvement with the Gran Consiglio so in this context the point is moot.

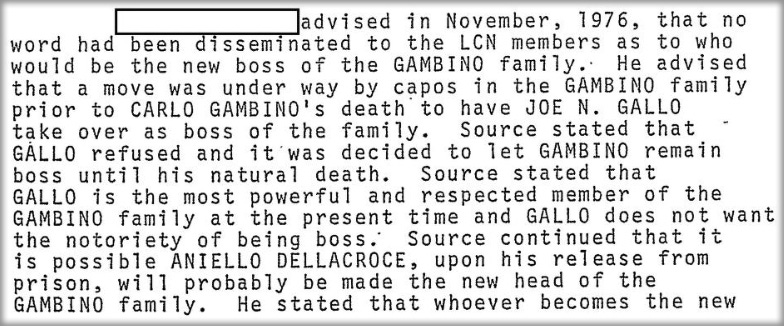

In 1923, when Gaspare Messina sent money to Giuseppe Caterinicchia, Nicola Gentile was himself the boss of Kansas City which placed him in relative proximity to Alabama. The Kansas City Family had its own ties to Alabama that will be explored later, but Caterinicchia serving as Gentile's single point of contact in Alabama lends itself to Caterinicchia holding significant rank, perhaps even representing the Alabama Family as boss. Stronger evidence that Caterinicchia could have been the Alabama boss comes via Boston leader Gaspare Messina's long-distance financial interest in Caterinicchia, a transaction of this nature indicating that Messina was contacting a man of near-equal rank in the Alabama Family. It's a well-known axiom in Cosa Nostra that water finds its own level and men of equal stature form bonds as a matter of protocol as much as they do through general comradery.

The mafia is comprised of its own classes and peer groups, with certain rules requiring that men of the same or similar rank represent their Families in formal matters between two groups. Protocol brought high-ranking members together in addition to other circumstantial connections. Although the evidence is limited, this is a logical interpretation of Messina and Gentile’s contact with Giuseppe Caterinicchia. Messina was a former New York Bonanno member living in Boston while the nomadic Nicola Gentile was at various times an influential member of Families in New York (Gambino), Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Kansas City, San Francisco, and Philadelphia, even serving as a rappresentante or consigliere for some of these groups. Gaspare Messina and Nicola Gentile’s connection to Caterinicchia may have had a personal dimension that we’re unaware of but within the mafia network it was likely political in nature and not local to Alabama.

A superficial understanding of Cosa Nostra, especially in these early days, may lead to skepticism over Giuseppe Caterinicchia's position given his apparent commitment to the Russellville farming community, nearly two hours northwest from Birmingham on today's modern roads. Uninformed outsiders tend to think of Family rappresentanti as "crime bosses" who micro-managed illegal operations in smokey backrooms, but if Caterinicchia was indeed the boss of Birmingham he wouldn't be the only American boss to operate some distance from his organization.

In Philadelphia, back-to-back bosses Joe Bruno Dovi and Joe Ida lived in New Brunswick and utilized Camden-based underboss Marco Reginelli to manage daily operations in their core Philadelphia and South Jersey territory. Longtime member John Cappello Jr. told an informant he rarely saw Ida when the latter served as boss. Even more extreme is Joe Bonanno, who for 20 years between the 1940s and 1960s lived much of the year in Arizona where he established a West Coast faction within his New York Family. Like the Philadelphia bosses in North Jersey, Bonanno utilized his underboss and various acting bosses to oversee activities in New York.