The Mafia's Senator in Wyoming

An unexpected member in an unexpected place: a story of political representation, the Colorado mafia, and "Americanization".

An offhand reference from a reliable San Jose FBI informant in 1963 identified an apparent Cosa Nostra member in Wyoming who served as a US Senator. This is difficult to believe at first glance, but this was more than a fleeting rumor when considering the full range of the organization this man was alleged to be part of and who reported it. Investigation into this individual highlights the enigmatic nature of Cosa Nostra while leaving us with more questions about historic mafia activity in the Mountain States. This article explores this man’s life and the possible mafia connections he maintained.

This article also serves as an analysis of Cosa Nostra’s internal systems of political representation in addition to exploring its relationship to politics external to the subculture. In my opinion it is impossible to separate them. Since its genesis Cosa Nostra has made considerable effort to combine its own internal politics with the political world around them. Sometimes this synthesis has even been achieved.

In order to understand Cosa Nostra’s relationship to politics and government, it’s important to first discuss the roots of Cosa Nostra in Sicily where the mafia has long influenced and even directly participated in island politics. From there we will examine the alleged mafia membership of this Wyoming State Senator, but this allegation must be properly contextualized within the political framework of Cosa Nostra — a framework built in the villages of Western Sicily.

An Introduction to the Mafia in Politics

Pop culture often references Cosa Nostra’s relationship to unethical politicians, highlighting corruption and backroom deals that serve the mafia’s underworld interests. This has been mythologized to some degree, though these relationships did exist. Much deeper relationships also existed, particularly in Sicily, where pentiti (repentants) have cooperated with the government and revealed inside information about the inner-world of Sicilian Cosa Nostra.

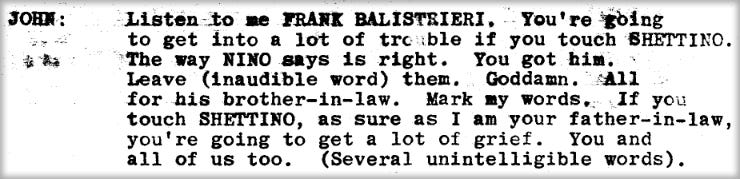

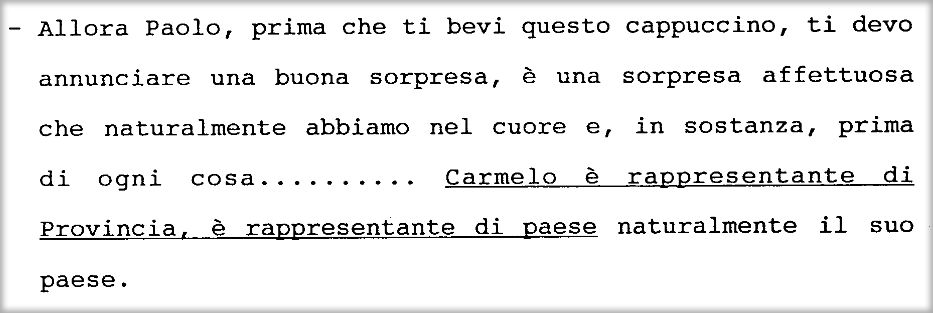

The Sicilian mafia did not simply influence or control politicians at various levels of government, they even inducted them into their organizations. In many villages throughout the island, mayors and municipal councillors were identified by sources as made members and even bosses. The traditional term for boss in Cosa Nostra is rappresentante (representative), an official term used almost exclusively by the bosses themselves when referring to their position, as evidenced on the FBI’s extensive recordings of US Cosa Nostra bosses during the 1960s. Even John Gotti was heard using this term on an FBI recording decades later. In addition to its criminal activity, Cosa Nostra is its own system of political representation and it is unsurprising the rappresentante would similarly become the highest representative in municipal government when synthesis is achieved.

In the village of San Giuseppe Jato, an enduring mafia stronghold in Palermo province, the Fascist government’s Prefect Cesare Mori presided over investigations that revealed three successive bosses of the San Giuseppe Jato Family simultaneously held the positions of town mayor and Cosa Nostra rappresentante during the 1910s and 1920s. The town’s council was comprised almost entirely of Cosa Nostra figures, many of them related by blood, including Vincenzo Troia who would become a significant figure in the United States before his 1935 murder in Newark. In addition to being town mayors and Cosa Nostra rappresentanti, the men identified in these dual roles in San Giuseppe Jato were all cousins.

Vincenzo Troia is believed to have been the acting boss of the San Giuseppe Jato Family and deputy mayor on behalf of his mayor-rappresentante cousin who was in hiding, with Troia himself absconding to the United States in the mid-1920s. The mafia leadership of San Giuseppe Jato scattered after participating in the murder of a rival political candidate several years earlier that attracted intense investigation from the Prefect Mori. The victim was not involved with the mafia and Cosa Nostra “defensively” murdered him for attempting to unseat the mafia’s municipal power. Troia’s 1935 murder in Newark was similarly the result of him trying to challenge the local Cosa Nostra power structure, though in his case it came from within.

Though law enforcement speculated Vincenzo Troia’s murder was a dispute over the “Italian lottery”, Nicola Gentile revealed it was an internal political conflict between Troia and the local Newark rappresentante. Gentile also described how Vincenzo Troia had previously climbed to the highest ranks of the American mafia soon after arriving in the United States, being elected capo over a would-be Commission formed in the wake of the Castellammarese War, though he didn’t end up serving in this capacity.

Nobody called the position rappresentante dei rappresentanti, a mouthful, though its definition would match given the capo dei capi was a purely political position within early Cosa Nostra. Joe Bonanno was adamant in his memoir that capo dei capi was an invention, with the Sicilian mafia equivalent capo consigliere being the true terminology for this position. Bonanno’s capo consigliere makes sense when considering Nicola Gentile’s account of the capo dei capi presiding over the Gran Consiglio, a pre-Commission advisory and mediation board. The Gran Consiglio was involved in national meetings of rappresentanti, referred to as the Assemblea Generale, which met to discuss matters of importance that impacted the broader Cosa Nostra organization before the Commission was formed in 1931. Capo dei capi Giuseppe Morello described the Assemblea Generale and Gran Consiglio in an early 20th century letter written to a Chicago mafia leader.

Regardless of the preferred language, the capo dei capi or capo consigliere was not so much a criminal “super-boss”, but rather an administrator of Cosa Nostra whose duties involved constant political conferencing, leaving the activities of his Family to be managed by underlings. These men shifted seamlessly from diplomacy to violence as it suited them. Vincenzo Troia didn’t end up taking the position of capo over the new Commission, as Salvatore Maranzano protested and assumed the original position of capo dei capi through political manipulation, but San Giuseppe Jato still factors heavily into the shared history of the mafia in the United States and Sicily. A Sicilian pentito described both Troia and Maranzano as active participants in Sicilian municipal politics before their arrival to America, influencing Palermo politicians to work in their favor.

Though the Prefect Mori’s efforts temporarily halted San Giuseppe Jato’s synthesis of Cosa Nostra with local government, San Giuseppe Jato resumed its tradition as a “mafia municipality” after the fall of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist government. Immediately following World War II, Vincenzo Troia’s brother Giuseppe assumed the role of both mayor and Cosa Nostra boss in San Giuseppe Jato, a trend seen throughout the island during the 1940s. Giuseppe Troia was a practicing doctor, a profession not uncommon to Sicilian mafia members, particularly those involved in politics.

The phenomenon of mafia members holding office was not limited to rural inland villages, as Dr. Melchiorre Allegra, the same source who discussed Vincenzo Troia and Salvatore Maranzano’s involvement in politics, identified Palermo’s Lucio Tasca Bordonaro as a fully-initiated fratello (brother) in Cosa Nostra during the years before he took on the elected role of mayor. Bordonaro was the first post-Fascist mayor of Palermo, assuming this role around the time Dr. Giuseppe Troia became mayor of San Giuseppe Jato. In addition to being a practicing medical professional, Dr. Allegra was himself a member of Cosa Nostra who made significant efforts to involve himself in island politics.

Dr. Allegra’s account of Lucio Tasca Bordonaro illustrated how Bordonaro was able to serve as a helpful liaison between Cosa Nostra and government. Both men interacted closely with San Giuseppe Jato politician Antonino Pulejo, Vincenzo Troia’s cousin, who also served as the local mafia boss beginning in the mid-1910s. Pentiti have indicated Cosa Nostra leaders were selective in who they allowed to contact these highly-placed members who provided Cosa Nostra access to the political arena. As a result, few sources are able to shed light on them.

It was often mafia members from the professional and upper classes who assumed positions in government, a pattern that can be seen outside of Cosa Nostra. One of Dr. Giuseppe Troia’s predecessors as both San Giuseppe Jato mayor and Cosa Nostra rappresentante was his relative, the aforementioned Antonino Pulejo, an esteemed lawyer and socialite. Pulejo was a personal friend of Dr. Melchiorre Allegra and they operated in the same exclusive circles inside and outside of Cosa Nostra, though the two circles largely overlapped.

Dr. Allegra told authorities how Antonino Pulejo’s daughter was arranged to marry a friend of Allegra’s who was recently inducted into Cosa Nostra, this man being a lawyer like Antonino Pulejo. The trend of attorneys practicing the laws of the state and Cosa Nostra together can be seen in the United States, where Los Angeles boss Frank Desimone assumed power in the 1950s after a career as a practicing attorney. Desimone was the son of an earlier Los Angeles rappresentante and they were among the upper classes of Cosa Nostra. The Desimones previously lived in Pueblo, Colorado, where an early mafia Family existed.

Dr. Allegra and famed pentito Tommaso Buscetta both described how this outwardly respectable section of Cosa Nostra membership formed their own peer group, socializing with made members of their own type. Buscetta explained how the role expected of them within the mafia corresponded to this identity — they weren’t expected to function in the same capacity as other members, rather they were expected to carry out a more valuable function. They didn’t operate like thieves and bandits, what we now call “gangsters”, though they all coexisted together in Cosa Nostra.

This trend was not exclusive to early generations of Sicilian mafia members. The extensive cooperation of Sicilian pentiti has led to the identification of more recent figures who held positions in government while maintaining membership in Cosa Nostra Families, particularly those involved with the long-influential Christian Democrat Party. The Family in the Brancaccio neighorhood of Palermo is notorious for its “political engagement”, producing Gioacchino Pennino, yet another doctor who took the blood oath into Cosa Nostra alongside his Hippocratic Oath. He was an influential Christian Democrat politician and freemason who turned informant and revealed the deep corruption inherent in the party. The capomandamento (district boss) of Brancaccio was Giuseppe Guttadauro, a practicing surgeon who oversaw a major hospital and was active in political circles.

One historic Italian politician of particular note is Vittorio Orlando, who served as Prime Minister of Italy from 1917 to 1919 while simultaneously holding office as Minister of the Interior. He would go on to join the Italian Senate 25 years later and held other significant political posts during his lifetime, which began in 1860 and ended in 1952. Orlando was active in politics until his natural death, mirroring another position he held until his passing: Cosa Nostra member. Tommaso Buscetta identified Vittorio Orlando as a made member within Buscetta’s own Porto Nuovo Family in Palermo, though Orlando would reside in Partinico, not far from San Giuseppe Jato, where he associated with local mafia leaders.

Another alleged member with nearly the same stature was Bernardo Mattarella of Castellammare del Golfo who held numerous cabinet posts until his passing in 1971. Mattarella’s sons Piersanti and Sergio followed him into politics, Sergio Mattarella today being President of Italy. Piersanti Mattarella served as President of the Regional Republic of Sicily before his execution at the hands of Cosa Nostra in 1980. Their father Bernardo was intimately familiar with the mafia, being identified by pentito Francesco DiCarlo as an amico nostra.

Bernardo Mattarella’s compaesano Joe Bonanno, rappresentante of a New York Family, referenced his personal friendship with Bernardo Mattarella and stated the two men had grown up with one another in Castellammare del Golfo. Indeed, both Bonanno and Mattarella were born in 1905. In his memoir A Man of Honor, Joe Bonanno states that Bernardo Mattarella headed a red carpet welcome party for him in Rome when the New York boss arrived for a 1957 Italian visit alongside the son of publisher Generoso Pope, Fortunato. Bonanno believed Mattarella to be Minister of Foreign Trade at the time, though he was in fact Minister of Posts and Telecommunications, a relative triviality given an alleged Cosa Nostra member held a ministerial position.

There are indications these Sicilian mafia politicians served as emissaries to other Cosa Nostra groups internationally. In the 1960s multiple FBI informants reported on a traveling group of politically-connected Sicilians who arrived in Chicago where they were greeted by Wisconsin-based Bonanno member John DiBella. This group reportedly traveled around the United States visiting cities with local Cosa Nostra Families where they were hosted by Family leaders and dined with members.

A San Jose FBI informant reported a conversation with San Jose Family captain Angelo Marino who told the informant one of these Sicilian men was the “Mayor of Palermo”. The esteemed guest had recently stayed at the home of Marino’s father Salvatore, a former capodecina and ex-Pittsburgh member with relatives in the Milwaukee Family. Salvo Lima, who was murdered by Cosa Nostra in 1992, had been the Palermo mayor for four years at this point and would continue in the role for six more years, indicating it was Lima who visited San Jose. Salvo Lima would later become a member of European Parliament and was one of the most powerful Christian Democrat politicians prior to his murder.

Confirmation that the traveling “Mayor of Palermo” was Salvo Lima comes via contemporary newspaper accounts. Lima and a group of other Sicilian politicians headed a tourism campaign called “Ritorno”, intending to encourage transatlantic tourism among Italian and Sicilian expatriates living in America. Newspapers describe how Lima and his “Ritorno” entourage indeed visited the United States in Fall of 1962, the same period described by the San Jose informant. Lima not only attended meetings and galas with powerful legitimate figures in 1962, he had also visited the year previous, meeting Ted Kennedy and other US politicians in 1961. Mainstream coverage of these visits naturally makes no reference to Salvo Lima’s appointments with American Cosa Nostra leaders, a fact known only to mafia insiders.

Though Tommaso Buscetta knew the inner-workings of Palermo’s mafia like few others, Buscetta stated he did not know if Salvo Lima was a Cosa Nostra member. He did, however, identify Lima’s father Vincenzo as one, lending itself to the informant’s information given the nepotistic nature of mafia membership, the traditional mafia preferring to recruit through blood and kinship. The Bay Area informant’s revelation, when combined with Dr. Melchiorre Allegra’s deposition, tells us there were at least two Palermo mayors between the 1940s and 1960s who held membership in Cosa Nostra, Lucio Tasca Bordonaro and Salvo Lima.

San Jose capodecina Angelo Marino told the Bay Area informant the Mayor of Palermo, who we know to be Salvo Lima, was an “official” of Cosa Nostra who carried out international duties for the organization. The basic function of these contacts is made evident by the traveling Sicilian contingent’s tour of the United States where they met with Cosa Nostra leaders in various locations. Perhaps the social and political stature of members who held office lent itself to larger diplomatic activities on behalf of the Sicilian mafia: they were representing their own secret government in Sicily while publicly representing the Italian government. This distinction is important — the Sicilian mafia does not believe Italian government is legitimate when it comes to their own affairs. They are their own government and a mafia member in political office serves Cosa Nostra first and foremost. Salvo Lima learned this in 1992 when a motorcycle-riding mafia gunman executed him weeks before a national election.

There is no indication the San Jose informant was shocked by this revelation about a sitting mayor with Cosa Nostra membership in Sicily. Many Sicilian pentiti similarly shared information about mafia politicians with a certain nonchalantness that suggests they understood Cosa Nostra has a built-in capacity for members of this nature. The FBI informant received the information about Salvo Lima from a leader in the San Jose Family, an organization with strong Sicilian roots, and it can be inferred that these old-fashioned Sicilian-centric American organizations understood the versatility of Cosa Nostra membership. No matter where the mafia ended up in the United States, the system and its processes came from the organization’s Sicilian ancestry.

High-ranking journeyman mafioso Nicola Gentile wrote in his memoirs how the early American Cosa Nostra groups similarly had professionals who involved themselves in local politics, though he did not identify any members who held significant political office. He did identify doctors who held high-ranking positions in American Families and some of them rubbed shoulders with local politicians. This included leaders in the Pittsburgh and Cleveland Families to which Gentile belonged at different times. American Cosa Nostra was created in Sicily’s image, most if not all of its initial members having been inducted in Sicily, and the history of Cosa Nostra in both locations is deeply intertwined.

A lack of sources within the historic American mafia make it difficult to identify the full range of activity of its early figures, though there are examples of early bosses and other Cosa Nostra members who held positions in local politics, particularly in Chicago. It can be assumed political office was more difficult for American mafiosi to obtain given Sicilians in the United States existed in smaller, insular communities and didn’t have an entire island of paesani at their disposal. Not everyone in America was part of their subculture and mafia membership became equated with organized street crime rather than self-government. The mafia still tried to achieve synthesis with the professional and political world in later decades but the effect was greatly diminished as law enforcement and the public became aware of Cosa Nostra.

Dr. Gregory Genovese was a practicing dentist in addition to being the son-in-law of Joe Bonanno and a San Francisco Cosa Nostra member. Dr. Genovese was ramping up involvement in local Bay Area politics with the support of Family rappresentante Joe Cerrito before his father-in-law’s notoriety ruined his chances. Along with his marital relation to Bonanno, Dr. Genovese’s father was a member of the Pittston and Bonanno Families. Had Dr. Gregory Genovese been a generation older and made similar attempts during an ealier era, he might well have succeeded in achieving a form of synthesis between underworld and overworld politics like the other examples given here.

There are indications American Cosa Nostra saw the value of inducting politicians even in the modern era and at times succeeded. Bonanno capodecina Frank Lino became a cooperating witness in the early-mid 2000s and described how he served as a delegate from New York who met with the Bonanno Family’s decina based in Montreal, Canada. Lino unintentionally created an international controversy when he revealed Alfonso Gagliano was a made member of the Bonanno Family based in Montreal.

A former Minister of Labor and Amabassador to Denmark, Gagliano was accused of political corruption but had no outward signs of “gangsterism” save for documented social and professional relationships with mafiosi from Agrigento who were far more overt in their criminality. Alfonso Gagliano had previously been a public accountant and a number of these figures used his services. Cosa Nostra will use any resource available within its own network, be it professional, political, social, or criminal.

Alfonso Gagliano’s seemingly contradictory nature can be understood fairly easily when examining his background. Gagliano was from the village of Siculiana in Sicily’s Agrigento province, an area that produced many of the Bonanno Family’s Montreal members along with the aforementioned Nicola Gentile and a seemingly endless roll call of infamous names. Siculiana itself was noted for having a degree of synthesis between Cosa Nostra and municipal government, not unlike San Giuseppe Jato in previous decades.

I spoke with former Gambino associate Salvatore Mangiavillano whose relatives were involved in Cosa Nostra in Agrigento and he had personal knowledge of one Cosa Nostra member who served as the longtime mayor of Naro, a village to the west of Siculiana. Mangiavillano was a blood relative of the man, this mafia mayor being his grandfather. It appears Alfonso Gagliano’s dual membership in Canadian government and Cosa Nostra was a reflection of his Sicilian mafia roots. The insular villages of Agrigento, where there is evidence of mafia-like activity dating back nearly 200 years, is an ideal climate for this form of symbiosis between two different forms of government.

Though he was a resident of Canada, Alfonso Gagliano was until recently the only known North American Cosa Nostra member to have served at the highest levels of government. Since the Gagliano revelation, the names of multiple Chicago politicians have also been revealed to be fully-initiated members of the local Family in decades past. However, research has uncovered the name of another man with alleged mafia membership who was elected to high political office. Like Gagliano, this man is believed to have been formally affiliated with a Family based in the United States yet resided in a remote outpost far from the organization’s base of operations. Unlike Gagliano, this man was not Sicilian nor does he have any obvious ties to the subculture of Cosa Nostra. He was not Canadian, but a citizen of the United States.

Rumors of a Senator With Mafia Membership

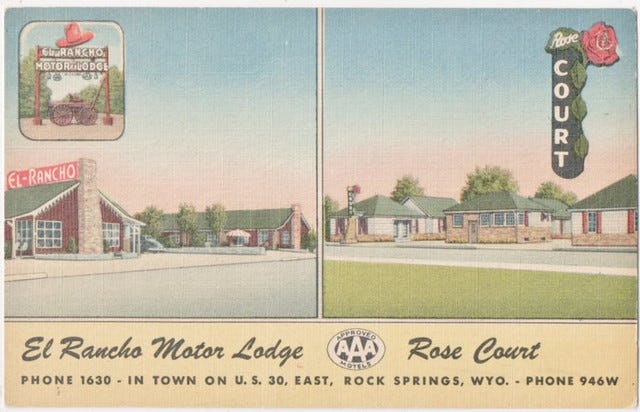

In 1963, San Jose Family member Salvatore Costanza, one of several FBI informants in that Family, reported that fellow San Jose member Alex Camarata referred to a "Louie Boschetto" as a Cosa Nostra member who was a "senator of some kind". Costanza was told this senator owned the El Rancho motel in Rock Springs, Wyoming, and that he was being used as a point of contact to monitor and report on the activities of San Jose member Pete Misuraca, a visitor to Wyoming. Misuraca came from a deep line-up of mafiosi in Detroit and New York City, including his elder brother John Misuraca who served as Colombo Family underboss for a period. Alex Camarata, the original source of the information on US Senator “Louie Boschetto” as cited by Costanza, was the son-in-law of John Misuraca, making the activities of his wife’s uncle Pete Misuraca a matter of personal relevance. It turns out Boschetto was a real man involved in Wyoming politics, but his connection to Misuraca is less obvious.

The younger Misuraca brother in San Jose was something of a misfit among his relatives, having a reputation for ineptitude and making trouble. Like Sal Costanza, Pete Misuraca was himself an FBI informant for a period. There are no documented references to this Mountain State senator in Misuraca’s cooperation from what I’ve been able to access, though our view into these FBI interviews is limited, with redactions occasionally blocking out entire segments. There are numerous other reports from these informants we can’t currently obtain. Fortunately there is other information available about the man in question.

Records show the El Rancho Motor Lodge in Rock Springs was in fact owned by a former Wyoming State Senator named Louis Boschetto (1898-1977), as reported to the FBI by Sal Costanza. The El Rancho was described as the “biggest motel” in Rock Springs and Boschetto owned an additional motel called Rose Court. The Boschettos were Northern Italians who came from Austria and Louis lived in Wyoming for most of his life. Nothing in his background jumps out as an obvious Cosa Nostra connection except for this discussion among made members, where Boschetto was identified as a Cosa Nostra member and an apparent point of contact for members visiting Wyoming.

Louis Boschetto was ostensibly an upstanding citizen, being State Deputy for the Wyoming Knights of Columbus in the late 1940s to early 1950s and holding influential positions in other civic groups. In 1938, Boschetto and an in-law patented a type of customized fishing equipment, Wyoming being something of a paradise for outdoor recreation. Records confirm he was a member of the Wyoming State House of Representatives circa 1950 and a Democrat. Louis Boschetto was also a leading member of the Highway 30 Association and he was no longer involved with the Senate when San Jose informant Sal Costanza made reference to him, though he remained active with the Democrat Party in Wyoming.

A certain amount of skepticism is necessary when reviewing FBI reports that identify Cosa Nostra members. Sources can be mistaken, though made members themselves have strict definitions of membership — there is only one definition — and members are generally correct when identifying one another. In the hierarchy of sources, member informants and FBI recordings of members in conversation with each other are our best resource for reliable intelligence on Cosa Nostra membership next to cooperating witnesses and memoirs. In this case, Salvatore Costanza was told by another mafia member that Louis Boschetto was a made member like them. The other identifying information is correct.

Rock Springs

Louis Boschetto’s residence in Rock Springs, Wyoming, could tell us more about his involvement in Cosa Nostra via environmental factors. Rock Springs had a long history of local corruption and criminal activity, both as a "cowboy town" earlier on and as a regional hub for organized criminal activity and municipal corruption. There was early criminal activity documented among Northern Italians in Rock Springs, where the Boschettos moved in 1931 after having spent a number of years in another remote Wyoming town close to Utah.

Rock Springs attracted Italian immigrants through its mining opportunities. The mountainous far-north of Italy where Boschetto and other Rock Springs Italians came from provided experience in this trade and through chain migration they arrived to areas where they could utilize existing talents. Countless Italian colonies formed around mining settlements in rural parts of America, Rock Springs being one of many in the Mountain States. Louis Boschetto began as a miner and it appears most of Rock Springs’ Northern Italian element arrived there for the same reason.

There is no clear indication what, if any, relationship this early Northern Italian criminal element in Wyoming had to established Cosa Nostra groups in terms of association or affiliation, but there must have been a relationship to the national Cosa Nostra network if a reputable Austro-Italian politician who spent his entire life in Wyoming became a fully-initiated member who could be tasked by the San Jose Family to watch over a troubled member visiting Wyoming. These relationships don’t manifest out of thin air, but are the product of intricate relationships and time-honored mafia protocol.

If Louis Boschetto was Sicilian, especially from a mafia-dominated village as Alfonso Gagliano was, it would be fairly easy to place him in the mafia network. These networks were established along compaesani lines, with mafiosi from the same town or region maintaining contact via letter and frequently traveling to areas where their relatives and compari lived and operated. In the context of Cosa Nostra, these networks expanded beyond hometown affinity to include “friends of friends”, but the patterns are consistent and we can often predict association if not affiliation by following them. Boschetto’s Northern Italian heritage in what was historically Austrian territory makes him extremely difficult to place using background and location alone.

An unidentified FBI informant reported how the American mafia initially only allowed Sicilian-born members, then came to accept American-born Sicilians, followed by Calabrians, Neapolitans, and finally other Italians, in that order. Other informants reported how the organization expanded its recruitment guidelines, originally allowing only Sicilians and eventually granting membership to members of mainland heritage. This basic evolution of the American organization is undisputed.

A summary in the FBI file for Neapolitan-born Genovese Family capodecina Ruggiero “Richie the Boot” Boiardo notes the belief that US Cosa Nostra Families began inducting non-Sicilians around 1915. Nicola Gentile’s account supports this, describing a group of criminal Neapolitans and Calabrians inducted into the Pittsburgh Family in the late 1910s. This became increasingly common in urban Cosa Nostra Families through the process of Americanization and the development of the Italian-American identity, though it was not limited to “Americanization” or the United States alone.

Even Cosa Nostra in Sicily has recruited non-Sicilians into their organization in recent decades. Pentiti have reported the induction of members from the Southern Italian mainland, though these members were typically high-ranking members of mainland Italian groups like the Neapolitan Camorra. There are parallels between the Sicilian mafia and mainland groups, but these organizations are not viewed by Cosa Nostra as u stessa cosa (the same thing), so they cannot recognize each others’ membership. Various accounts suggest the mafia has inducted leading members of the Camorra in order to include them in formal Cosa Nostra politics that further the criminal interests of all involved. The known examples of this process are exceptional in the greater history of Cosa Nostra but illustrate a willingness to expand the Sicilian mafia beyond traditional ethnic boundaries even in its homeland.

Sicilian-born Cosa Nostra members have long had a presence in mainland Italy, too. There have been formally recognized Cosa Nostra Families in select mainland cities and this influence has stretched further north on occasion. These members were initially part of Families on the island of Sicily, though, and most of these mainland excursions are in the lower half of Italy where pan-Italian underworld politics are easily understood by all parties regardless of the specific organization(s) or ethnicities governing them.

Louis Boschetto’s home province in South Tyrol is in the extreme north, which makes him an outlier even among outliers in terms of Italian-American mafia membership. Using Sicilian precedent to understand Louis Boschetto’s American membership is less meaningful given his inclusion in Cosa Nostra inevitably came through local American relationships. Still, Sicily’s capacity for expanding its recruitment practices to include non-Sicilians shows a versatility reflected to an even greater degree in the United States.

Though it is evident Cosa Nostra did ultimately allow most if not all Italian-Americans to join so long as they had heritage from any part of Italy, the organization still recruited primarily from Southern Italian populations. Most of the smaller US Families outside of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and New England remained heavily Sicilian throughout their existence. Some groups, as noted by a 1958 FBI informant, explicitly limited membership to Southern Italians from Sicily, Calabria, and Naples.

If Northern Italian figures in Wyoming did become Cosa Nostra members, it would seemingly be later in the timeline. Given Louis Boschetto didn't move to Rock Springs until 1931, it's more likely he received his membership after that point given the organization by then had opened itself to a broader range of Italians. This is speculation, but it is informed by what is currently known about the Americanization of Cosa Nostra, evolving from a purely Sicilian phenomenon to a pan-Italian group that still nonetheless conforms to the group’s Sicilian roots.

With few if any exceptions, American Cosa Nostra demanded that members uphold the Sicilian mafia structure, rules, and protocol even as the membership grew to include other Italians. This is mirrored in Sicily, where the induction of mainland figures into Cosa Nostra required the inductees to honor the traditions of Cosa Nostra rather than create a new, hybridized organization. Membership evolves but changes to the organization are rare, gradual, and still dictated by its Sicilian core. Though the traditional mafia is known to recruit some Sicilian members who are not ostensibly criminal, common ground with other Italian ethnicities under the banner of Cosa Nostra is often found in criminal activity above all else.

Regardless of whether he participated in illegal activity himself, it's possible Louis Boschetto became connected to the mafia through the Northern Italian criminal element in Rock Springs. Rock Springs Italian crime figure Pietro Zanetti, from Piedmont, lived in Las Vegas in the 1930s where he allegedly associated with Bugsy Siegel before returning to Rock Springs. If true, Siegel could have facilitated contact between Zanetti and the countless Cosa Nostra figures Siegel associated with in the area, assuming Zanetti didn’t have existing contacts prior to Las Vegas. Las Vegas would also put Zanetti in proximity with California Cosa Nostra members and the many other members from various US groups who traveled there. Pietro Zanetti is one possible connection between the mafia and Rock Springs, and therefore Boschetto.

John Anselmi was another Rock Springs crime figure of northern extraction. Like Louis Boschetto, the Anselmis came from Austria-controlled Northern Italy and settled in rural Wyoming. One of John Anselmi's sons, Don, became a Democratic Party chairman in Rock Springs before resigning in the late 1970s due to an investigation into embezzlement that targeted the longtime Mayor of Rock Springs. The reputation of the Anselmi family was well-known in Western Wyoming and they did little to hide it, though another Anselmi, Rudolph, was a contemporary Wyoming State Senator alongside Boschetto in the early 1950s and served as Democratic State Chairman.

Don Anselmi was accused of having organized crime ties to Arizona and a 1974 LA Times article alleged he was involved in gun running between California and Wyoming along with real estate scams. Don Anselmi's grandson wrote a memoir and a corresponding write-up mentioned how "rumors of his family's mob connections followed him" around Rock Springs. Records show John Anselmi's family lived in Los Angeles for a time in the 1920s and early 1930s before returning to Rock Springs, another California connection for the shadowy Northern Italians in this small Wyoming town.

Like Louis Boschetto’s ownership of the El Rancho motel, noted by San Jose member Sal Costanza, the Anselmis owned a motel in Rock Springs. Under the supervision of John’s son Don Anselmi, the family established the suggestively named Outlaw Inn, which like Boschetto’s El Rancho was located off the highway. The Outlaw Inn was used as a main meeting place for the Wyoming Democratic Party Louis Boschetto and Don Anselmi belonged to.

Their Austro-Italian roots, residence in Rock Springs, ownership of highway motels, and involvement in Wyoming Democratic politics suggests the Anselmis were close to former US Senator Louis Boschetto. The previous involvement of fellow senator Rudolph Anselmi with Boschetto in contemporary politics shows this connection went back further, too. Further evidence of a relationship is Louis Boschetto's nephew, who served as a pallbearer at the funeral of Don Anselmi's father John. An Anselmi worked at Boschetto's El Rancho motel, so the families were clearly close.

Another corrupt political figure close to John Anselmi's son Don during his own time as a corrupt Democratic politician was Frank Mendocino, Wyoming Attorney General, described by a criminal investigator as a "crook". Don Anselmi's position in the same political party as Boschetto and Anselmi's involvement in local municipal corruption, which is alleged to have been pervasive throughout the history of Rock Springs, suggests Boschetto himself was no stranger to corrupt practices during his time as a high-level Wyoming politician. Louis Boschetto’s alleged membership in Cosa Nostra certainly does nothing to detract from this theory, though there is no concrete evidence of crime or corruption on his part.

If Louis Boschetto was a mafia member in Wyoming, it may have helped that Rock Springs was a small town. He achieved much higher political office than the local municipality, but Boschetto’s status was in Rock Springs. It’s where he lived, ran his business, and both he and the Anselmis were active in Democratic Party activities from their Western Wyoming base, hosting meetings with their political allies at their roadside motels.

Returning to Sicily, we do see urban Palermo mayors and even European Parliament members with Cosa Nostra membership, but it is small villages like San Giuseppe Jato where the mafia achieved complete synthesis with local government. The framework of local government lends itself to the mafia, which governs its own jurisdictions through localized Families, though Cosa Nostra too has its own federal system via the Commission and earlier national governing bodies. Regardless of its own national processes, the conservative and local-minded mafia is by nature more at odds with federal government and it is no coincidence Cosa Nostra’s main antagonists are the Italian Carabinieri and the American FBI. It is local police that Cosa Nostra corrupts and it is their local political environment they seek to control — anything beyond that generally amounts to flirtation.

The mafia can achieve influence in federal politics but rarely sustains it. They do maintain local influence with some ease and this is particularly true for districts, neighborhoods, and villages in Sicily. Louis Boschetto was an alleged member of a Cosa Nostra Family, likely one led by Sicilians at the time he was initiated, so it makes sense his role would be similar to what we’ve seen in Sicilian history. He was a Northern Italian who achieved much higher office than mayor, but it is his relationship to the village-like Rock Springs that seems to have driven his status in public politics and made him an attractive recruit for Cosa Nostra.

Membership, Legal Representation, & Election

Membership in Cosa Nostra does not happen randomly nor is it defined by circumstantial factors alone like criminal association or participation in the same activities. Members of the same mafia organization might have nothing else in common aside from their affiliation with the same Family. As with the doctors and politicians mentioned in the introduction who share membership with bandits, the mafia has its own peer groups where the more rough and criminal element engage in activities within their own circle and others, like professionals and businessmen, similarly stick to themselves.

There is of course a spectrum of gray with some members resting in the middle, but recruitment has a highly specific process regardless of who is being recruited. All members must agree to take a blood oath to commit murder if asked, as the government of Cosa Nostra is like other governments in that it believes it has a monopoly on violence. However, Cosa Nostra members are not so much “licensed to kill” as much as they are forced to commit murder in order to maintain the organization’s power and renew their own individual license as representatives of the group.

Along with engaging in acts of violence when asked, another universal rule in Cosa Nostra is not to contact or cooperate with law enforcement. This is not only because the mafia has an enduring criminal nature and collaboration with authorities is counterintuitive to these goals, but Cosa Nostra also refuses to recognize the legal authority of anyone outside of their own government. They believe in self-policing through violence, but the mafia wouldn’t exist today if that was their sole method of mediation. As much as the mafia has earned its reputation for bloody conflict resolution, there is a more prevalent tendency to carefully cooperate within the guidelines of its own system.

A made member has a license to practice law. An associate can’t formally represent himself, so a made member stands in as his advocate, using Cosa Nostra membership to argue for a given outcome on behalf of the men who retain him as their representative. Like a real lawyer, backroom deals happen and Cosa Nostra members occasionally corrupt the system. The system itself is prone to exploitation and corruption, though it is still a system of representation and advocacy.

The term “advocate” is not lost on Cosa Nostra members. Commission members were formally referred to by the title avvocato, pronounced “avugad”, and this literally translates to “advocate” but is used in Italy to mean lawyer. The Commission was the highest level of the mafia’s federal government, showing the mafia used a legal lexicon when referring to its top representatives.

In addition to negotiating policy, Commission members were true political representatives. There were few national bosses elected to this position and many of them were assigned a set of other Family bosses who didn’t sit on the Commission but received representation through this avvocato. These formal relationships were generally based on longstanding political and compaesani ties but also sometimes common locale. Commission members could represent other organizations anywhere in the country, New York bosses representing groups as far as California, but examples like Chicago show how an avvocato could provide this service to Families within their own general region.

Whether it is a made member representing an associate or a Commission member advocating for another rappresentante, these representatives argue their point in earnest, seeking a favorable outcome for the defendant as it often means a reward for the lawyer himself. With representation comes compensation, though like an attorney in the American legal system, Cosa Nostra’s own licensed practitioners work “pro bono” for the right cause or when politics require them to do so. This can be self-serving in its own right, though there are close relationships between members, associates, and “civilians” in the subculture and not all members are cruel sociopaths. Members are motivated by a just outcome under the right circumstances and there are rules requiring high-level members to carry out these duties as part of their position.

The term “sitdown” is widely known to the public as the mafia’s preferred method of conflict resolution. This term was a street translation of what earlier American members called an arguimendo, literally meaning “arguing” but used to mean “arguing body”. This was a more formalized way of describing underworld trials and it was reported that a decision made at these meetings could be appealed, escalating to the Commission if needed. There are numerous accounts of issues within Families being taken to the Commission in this way, even disputes involving rank-and-file members.

There are many ways to win an argument and that is true for an arguimendo or sitdown. Former Colombo associate Bill Cutolo Jr. believes his father Bill Sr. was particularly adept at sitdowns not through sheer force of will but because of his ability to convince all participants the outcome was fair. Cutolo’s son may have been biased, but Gambino capodecina Michael DiLeonardo echoed this account in courtroom testimony, saying the elder Bill Cutolo was near-impossible to outdo in mafia trials.

Like Cutolo Sr., Michael DiLeonardo was a skilled mafia lawyer who served as designated Family representative at countless high-level sitdowns while he was capodecina. Michael was offered the position of consigliere at a relatively young age, an opportunity earned by demonstrating an advanced understanding of mafia law and its corresponding politics. He has commented his favorite part of Cosa Nostra was attending sitdowns and from speaking with him there is a sharpness when it comes to these subjects — the politics of American government and Cosa Nostra both.

This practice of arguimendo is not exclusive to one type of issue. Criminal disputes are resolved this way, as are negotiations pertaining to legitimate business deals. Sometimes these sitdowns concern matters that are purely organizational or political. Nicola Gentile’s duties as a traveling representative commonly involved matters of life and death, as is to be expected of this organization.

Other times these trials are social in nature, a personal dispute within the subculture that can best be settled by its highest representatives. The bigger picture reveals Cosa Nostra as a system of representation and just as politicians in American government often come from legal backgrounds, Cosa Nostra leaders are typically skilled lawyers within their own system. As outlined earlier, some of them were once licensed attorneys in the true sense who bridged a gap between the two conflicting systems of Cosa Nostra and federal law.

Philadelphia capodecina John Cappello Jr. was recorded telling an FBI informant the consigliere is “like a lawyer”. Another source used the same description, commenting how the consigliere is “not necessarily” an actual attorney in the professional sense, indicating it’s possible for the man in this position to be a real attorney in some cases, too. I will raise them one and say the consigliere is like the Attorney General. Joe Bonanno’s insistence that the capo dei capi position was in fact called the capo consigliere plays into this, showing how the term scales up to the highest position in national mafia politics.

The consigliere is regarded as the ultimate authority should a problem escalate and he advises the boss while representing the membership at the highest level within the Family. Sources have indicated it is the consigliere rather than the Family rappresentante who often serves as the arbiter when an arguimendo passes through the bottom-up chain of command. Former Bonanno underboss Salvatore Vitale testified how the consigliere was also responsible for announcing candidates in the election of a boss, suggesting the position was utilized for ceremonial purposes in Family politics in addition to its functional role on the street.

Stefano Magaddino was recorded in January 1965 educating two Bonanno leaders on the election process for the open boss position in their Family. They hadn’t elected a new boss for 34 years and the men were clueless as to how the process is formally handled despite their senior positions. Magaddino explained how the Family must agree on a candidate and the Commission in turn ratifies the decision. He told them the Commission will appoint an acting boss in cases of Family instability, but it is still the Family itself who elects someone as rappresentante.

There are no documented cases where the underboss or captains are elected. All sources, including recorded statements from bosses Magaddino and John Gotti, agree these positions are appointed by the boss. This carries significant weight, as captains are used as proxies in Family elections given not all members can attend these secretive meetings and the “at will” nature of a capodecina’s rank puts him at the mercy of Family politics just as the position gives him immense influence over said politics. Captains have been known to influence Family elections as a result of their vital position but the boss directly controls who serves in this capacity, making the capodecina capable of being both manipulative and manipulated himself.

Stefano Magaddino was recorded saying the capodecina position was “all-important” in the Family, indicating they served as a political gateway between the members and top leadership. Greg Scarpa’s participation in formal elections supports this, as it was his capodecina who organized a meeting with the members of his crew to collect their votes and discuss candidates. The men expressed their opinions, some of them conflicting, but ultimately decided on a unanimous vote, with Scarpa’s account showing clear influence from the captain. Other accounts of Family elections describe how captains attend a subsequent meeting where they cast a single vote on behalf of the entire decina.

With regard to consigliere, many sources have described an election process where this role is selected by the membership rather than chosen by the boss, making this position unique within the hierarchy. Interestingly, Nicola Gentile referred to the consigliere being appointed by the rappresentante rather than elected and later cooperating witnesses describe being promoted by the boss, suggesting the election process has been lost to time in some Families or the process is inconsistent. Mafia leaders like Joe and Bill Bonanno along with their cousin Stefano Magaddino referred to the consigliere election process, the chosen candidate being voted in. Different sources have given different accounts as to how a given member becomes the consigliere, though the duties of the position are largely consistent.

Tommaso Buscetta in Sicily provided some clarification on this, stating that in smaller Sicilian Families the consigliere is appointed and in larger groups it is elected. This plays into the political nature of Cosa Nostra, where factionalism and conflicting politics are an inevitability in Families who maintain larger membership and more leadership positions. As Buscetta indicates, a larger organization would gain political stability from the consigliere being elected by the different factions rather than appointed by the head rappresentante alone. As with “real” elections, Cosa Nostra’s elections are prone to manipulation and outright fraud, though other times integrity is upheld.

The FBI recorded a 1977 discussion between high-ranking Philadelphia members where longtime member Harry Riccobene commented there was “never” more than one candidate in the Family’s historic consigliere elections, hinting at a predetermined outcome. The men on the tape, including underboss Phil Testa, expressed dissatisfaction at being left out of the process, complaining how the Philadelphia Family’s elder members under Angelo Bruno were deciding the outcome without consulting the “young” leaders (Testa was 53-years-old). In contrast, the account of a 1980s Bonanno Family election for the acting boss position described how the leading candidate barely won, with nearly half the captains voting for a rival leader during these tense proceedings.

John Gotti’s “election” as boss was arranged behind closed doors so that all parties would vote unanimously. Colombo member Greg Scarpa told the FBI the mafia has a rule against “campaigning” for these reasons, citing the upcoming election of Joe Colombo as rappresentante. Scarpa said Colombo was actively breaking this anti-campaigning rule by seeking private meetings with other Family leaders in order to gain support.

A contemporary FBI recording of New England boss Raymond Patriarca with Greg Scarpa’s friend Nick Bianco highlights the “no campaigning” rule, with Bianco commenting to Patriarca he was only recently informed of the rule. Bianco was a newly made member who soon thereafter transferred from New England to the New York Colombos thus never having experienced the election of a boss. Patriarca acknowledged the anti-campaigning rule and voting process, though he explained violation of the rule would be ignored unless a significant number of captains opposed the candidate.

Raymond Patriarca also stated the Commission would influence the selection of new bosses they felt were suitable. When the visiting Bonanno leaders suggested this prospect to Stefano Magaddino, he was vehement about this only taking place if there was significant discord in the Family, with the choice of rappresentante otherwise being completely up to the Family’s own members. In his memoir, Magaddino’s cousin Joe Bonanno describes a meeting of his Family’s entire membership where attendees all voted at once to elect one of two candidates, with Bonanno taking the majority vote.

Greg Scarpa told the FBI he was asked by a senior leader to cast a vote for the new rappresentante and Scarpa was also allowed to vote on behalf of his imprisoned brother and another incarcerated member, indicating the Family at least went through the formalities of a proper election. Greg Scarpa’s triple vote went to Joe Colombo, the man accused of illegally “campaigning” behind the scenes. During a previous Family election that would later be denounced by the Commission, Scarpa cast the same three votes though another member questioned Scarpa’s right to speak for the incarcerated members. In both Colombo elections the membership was included in the voting process whether election integrity was upheld or not.

Following the 1962 death of longtime rappresentante Joe Profaci, his brother-in-law and underboss Joe Magliocco quickly rallied support from loyalists and rushed an election without properly consulting the Commission. As Greg Scarpa noted, it was customary to wait a duration of time before holding a formal election after the death of a boss, an observation noted by Bill Bonanno as well in one of his memoirs. The Commission refused to recognize Magliocco’s position because his Family was in the middle of a conflict with the rebellious Gallo brothers and other sources state a Family must wait until these troubles are resolved before a new rappresentante is recognized by the Commission. There are other examples of the Commission similarly suspending formal elections due to internal Family conflicts, as they did with the Colombo Family.

Despite popular belief, the underboss is not guaranteed the boss position following the death of the latter, though if he has significant political power or controls an influential faction he might become boss or retain his underboss position, as Neil Dellacroce did in the Gambino Family. There are indications the underboss loses his position immediately when a boss dies or steps down, while the captains aren’t demoted until the new boss is elected, as their rank is still required during the election process. The new rappresentante is allowed to choose his underboss and “reappoint” previous captains or name new ones. These demotions are part formality and part reality, as some captains lose their position permanently while others don’t.

Stefano Magaddino and other sources have described the Joe Magliocco dilemma, where Magliocco was called to account at a national arguimendo presided over by the Commission. In addition to being accused of plotting the murders of two rival bosses, Magliocco was shamed for not following proper protocol in getting himself elected boss. Joe Magliocco was recorded discussing the events preceeding this arguimendo on an FBI tape in Philadelphia boss Angelo Bruno’s office. Bruno explained these political processes to the hapless Joe Magliocco, who like Stefano Magaddino’s Bonanno visitors had not participated in a boss election for over 30 years.

Following the arguimendo in which he was criticized by the Commission and removed from defacto power, Joe Magliocco was forced to pay the travel expenses of visiting Commission members. Joe Magliocco was not killed for his indiscretions though the stress may have contributed to his natural death in 1963. It may not have been Magliocco’s underhanded attempt to gain power that bothered the the Commission so deeply, but the bullheaded way he approached Cosa Nostra’s rule of law. Joe Colombo followed the Commission’s processes even though he privately campaigned and manipulated the outcome behind the scenes.

It is noteworthy that despite occasional violations of protocol, none of the men who successfully became rappresentante openly proclaimed themselves boss without going through the motions of election protocol. They sometimes manipulate the process behind the scenes but maintain an aire of legitimacy within Cosa Nostra’s guidelines. Even when the outcome is predetermined and a boss is elected underhandedly it is done through careful navigation of Cosa Nostra politics, making sure the appearance of law is upheld.

FBI recordings of John Gotti show his own understanding of these techniques. Following a disagreement with longtime consigliere Joe N. Gallo, Gallo claimed that John Gotti could not demote him due to the elected nature of his position. Gotti explained on the tape how he would get around this by briefly demoting dissenting captains, appoint agreeable captains who would take Gallo down from the position, then return the original captains to their former rank. Joe N. Gallo was soon removed from his position thereafter, though it’s unknown if John Gotti achieved this result through the means he described.

Just as an ordinary citizen still essentially believes in many of the laws they break (speed limits being a prime example) and follows most of them them as a general rule, Cosa Nostra members operate similarly. It is not only the members who must believe in them, but the entire subculture. Friends, relatives, neighbors, and associates of Cosa Nostra members are expected to understand the basics of these principals and defer to the laws of Cosa Nostra and its licensed representatives. They understand that breaking these rules still requires careful navigation of them, as they are the laws of the society around them. Members have more status in this environment, but both Cosa Nostra and the communities it operates in require each other in order for their shadow government to exist.

At its core, the mafia in all periods of its documented existence in America and Sicily share this quality of representation. The nature of recruitment, promotion, and election offer differing accounts, but the way formal positions are used in the mafia center around this key function. Crimes, businesses, and even people themselves come and go, but Cosa Nostra remains a system of representation within its own defiant society and it mirrors the way we elect and utilize representatives even if it corrupts the process just as we do ourselves.

Cosa Nostra’s corruption is more immediate and direct, though objectively it cannot be called more violent when considering the wars, government-sanctioned executions, and other acts of aggression carried out by the state. Both the mafia and official governments claim a monopoly on violence, navigating their own legal parameters to justify actions that are by definition destructive.

This is not political commentary on my part, rather a simple truth that comes with governing bodies on any scale. It is up to the society to decide what constitutes a valid justification for violence and Cosa Nostra has drawn its line in the sand. It nonetheless remains a heated topic of debate inside and outside of Cosa Nostra as to what measures should or should not be taken in matters of human life. The American legal system holds these formal debates in a courtroom, while Cosa Nostra arranges for an arguimendo or sitdown.

This section may read like a diversion from the topic of Louis Boschetto, but it is essential to understand how and why someone from his background and position in society was seen as a candidate for membership in this exclusive subculture. Louis Boschetto was not an elected rappresentante in Cosa Nostra, but San Jose member informant Salvatore Costanza’s reference to Boschetto as a made member suggests he served as a Cosa Nostra representative in Wyoming just as he was a senator for the state in which he lived. A basic comprehension of how Cosa Nostra governs itself is essential to understanding its relationship to external politics and the middleground where these elements meet.

All Members Belong to a Family

Despite the impression given by television, no Cosa Nostra member is required to commit crimes other than murder. They are encouraged to participate in crime and corruption if that’s their calling, and one could argue that Cosa Nostra mirrors other governments through its inherent potential for corrupt practices, but in terms of the organization’s operation the members themselves are not required to commit crime and have no “criminal quota”.

No member has ever been punished for refusing to participate in a gambling operation, robbery, or kickback scheme. If they are already engaged in those activities, however, they are expected to do as the leadership asks. This is as true for other activities and resources under a member’s control as it is for overt crime. It’s a fine distinction but it exists.

Recruitment therefore happens for many different reasons. Sometimes members are inducted into the organization impulsively, but even then the process has remained consistent. It is a strict system dating back to Sicily in the 19th century, if not earlier. A proposed member is formally sponsored, inducted, and assigned to a specific Family and he must report to a fixed supervisor, either a capodecina or the Family administration itself. Just as the Bonanno Family’s Montreal decina reported to the Bonanno leadership in New York, individual members in a remote location can report to a capodecina or other leader in a different city or even state. Typically these assignments do follow geographic patterns even though it is not an absolute rule.

Proximity suggests the Cosa Nostra element in Rock Springs was part of the Colorado Family given it was the closest mafia group and Colorado members had ties to Wyoming via Prohibition-era bootlegging. Though Denver is the most well-known Colorado city and most mafia-related publicity focused on the Denver underworld, the historic leadership of the Family was based in Pueblo. The Pueblo-based leadership was primarily from Lucca Sicula, Burgio, and surrounding villages in Agrigento and nearby parts of Trapani province like Poggioreale and Salaparuta. This group was likely formed along compaesani lines, as virtually all Families were, expanding their membership to other Italians through Americanization.

Frank Desimone, the lawyer and Los Angeles boss, was born in Pueblo. His father Rosario was a Pueblo member before transferring to Los Angeles and soon becoming the Family rappresentante. Rosario Desimone was from Salaparuta in Trapani province, though he married a woman who came from Lucca Sicula like many of the Colorado members. Frank Desimone is the product of two compaesani groups known to have provided members in the early Colorado Family. The Desimones provide a connection between Cosa Nostra in California and the Mountain States just as they connected the Trapani and Agrigento groups in Pueblo through marriage and blood.

Pueblo was a significant location in the early US mafia network, as noted by the Agrigento-born Nicola Gentile. Gentile helped negotiate politics stemming from the 1922 murder of leader Pellegrino Scaglia and open warfare that followed. Relatives of Scaglia sought national intervention, with Nicola Gentile serving as their advocate in a trial that involved the highest levels of national mafia leadership. Nicola Gentile’s national position revolved largely around his Agrigento heritage that connected him to groups with members of a similar background.

One of the men represented by Nicola Gentile was Vincenzo Chiappetta from Poggioreale, part of Trapani province that borders Agrigento. Like the Desimone marriage to a woman from Lucca Sicula, Chiappetta from Trapani was a relative of Pellegrino Scaglia from Burgio, Agrigento. Vincenzo Chiappetta and other loyal Scaglia relatives ended up in Missouri, with Chiappetta becoming an influential senior figure with the Kansas City and St. Louis Families. An early St. Louis boss was from Burgio like Pellegrino Scaglia and other Missouri figures fit into a corresponding compaesani network, making the state a destination for the fleeing Colorado figures.

Aware of his history in the organization, the FBI later sought out an elderly Vincenzo Chiappetta for an interview. Perhaps seeing his mafia life behind him, Chiappetta was surprisingly candid while carefully denying his own membership and direct knowledge of Cosa Nostra. He admitted having read extensively about the 1957 Apalachin meeting and provided commentary that brings to mind his history with national mafia politics via Colorado.

Vincenzo Chiappetta suggested the Apalachin affair was organized to prevent warfare following the shooting of Frank Costello and murder of Albert Anastasia in New York. He felt the attendees who achieved status as legitimate “businessmen” with “positions of responsibility in their various communities” stepped in to mediate the conflict so as to protect their status. He emphasized the distinction between these different types of men.

Vincenzo Chiappetta told the FBI the Apalachin attendees were largely involved in “rackets” and therefore it required “gangster leaders” to mediate the conflict. He noted how a dispute involving “legitimate Italian businessmen” would similarly involve other “legitimate Italian businessmen” to settle the conflict. Note that he didn’t say these “legitimate” businessmen would use the American legal system to settle the matter. This draws back to the accounts of Sicilian pentiti like Dr. Melchiorre Allegra and Tommaso Buscetta who described the more socially acceptable and outwardly professional and political class of Sicilian mafiosi traveling in their own circles and operating within their own peer group.

This distinction between the hoodlum, bandit, and gangster element in contrast with the ostensibly legitimate element comes up repeatedly from former members of Cosa Nostra in Sicily and the United States. Gambino underboss Sammy Gravano makes a distinction in his book between what he terms “gangsters” like himself opposed to his boss Paul Castellano, who Gravano calls a “racketeer” for his business-oriented goals. Gravano described these differences as a source of tension between the different classes of members, leading to Sammy Gravano and John Gotti deciding to kill Castellano in 1985. These distinctions are an obvious catalyst for factionalism and political conflict.

The former underboss of Philadelphia, Phil Leonetti, explained to an interviewer how there was a clear separation in the Philadelphia Family between Sicilian “businessmen” like boss Angelo Bruno and Calabrian “shooters” like his uncle Nicky Scarfo. Leonetti elaborated, saying Scarfo held a philosophy that “shooters” like them had to prove themselves in the organization through ruthlessness to strike a balance with the Sicilians who achieved their status as “businessmen”. Leonetti’s perspective included an ethnic element, associating one class of member with the Sicilians and the other with Calabrians, the two major factions that populated his Family. He also said when Phil Testa became boss he promoted a fellow Sicilian to underboss despite his Calabrian friend Nicky Scarfo expecting the position and emphasized how this decision was motivated by ethnic preference.

The terms used by Sammy Gravano and Phil Leonetti reflect those used by Vincenzo Chiappetta to describe the different peer groups in Cosa Nostra. Gravano didn’t mention an ethnic component as Leonetti did, though none of Castellano’s killers came from a Sicilian mafia lineage like Paul Castellano. Castellano’s lineage was filled with high-ranking members of Palermitano heritage, his close relative Carlo Gambino having been the previous boss and Paul’s father Giuseppe serving as a historic capodecina. Sicilian pentito Giovanni Brusca from Vincenzo Troia’s hometown of San Giuseppe Jato said members in urban Palermo, where Castellano had his roots, mocked the men from inland villages, calling them “peasants”. John Gotti and Sammy Gravano saw themselves as hardworking peasants challenging the mafia’s own aristocracy.

Vincenzo Chiappetta reflected on changes within the organization in his FBI interview. He admitted having read about the mafia as a boy as one would read about outlaws in the “West”, perhaps unintentionally invoking his time in Colorado and its location on the American frontier. He said if the mafia existed, it would be declining given younger Italians and Sicilians no longer “subscribe to the regimentation” of Cosa Nostra as the older immigrant members once did. This is a sentiment echoed by countless older members who offered their perspective, among them Joe Bonanno.

Vincenzo Chiappetta described his business and social relationship with early San Francisco boss Francesco Lanza, the food industry bringing them together from afar. As Family rappresentante, Lanza projected a legitimate image and was a fixture in the Bay Area’s Sicilian community, his son James taking on his father’s same title of boss decades later while selling insurance. Chiappetta’s reference to the “businessmen” with influence in their “communities” draws comparisons to Louis Boschetto, who may have crossed paths with individuals familiar to Vincenzo Chiappetta in Colorado and the Mountain States. Chiappetta admitted knowing a local Kansas City politician quite well and being involved in various Italian/Sicilian civic groups and “benevolent organizations”. He told the FBI he came to the United States in 1905 at age 18, which places his formative years with Cosa Nostra in America.

Though he spoke in generalities and was no doubt projecting an image for the FBI, Vincenzo Chiappetta’s interpretation of the Apalachin meeting after Albert Anastasia’s murder sheds a crack of light on his earlier experience at a national arguimendo concerning the murder of Colorado boss Pellegrino Scaglia, his relative. Both events led to a national meeting and though the governing bodies had evolved in some ways by 1957, the overall process is not dissimilar. His perspective, though it was tailored for the FBI, does offer commentary on his experiences in Cosa Nostra and therefore the Mountain States where he may have encountered a dynamic range of mafia affiliates.

A former Pueblo member commenting on the decline of “regimentation” takes us to New York, where another former Colorado member unexpectedly appeared. Cooperating witness and Lucchese leader Al D’Arco recounted generations later how an ancient member of his decina in Brooklyn, Paolo D’Anna, participated in the same Colorado war before moving to New York and transferring membership. The murder of Pellegrino Scaglia and the surrounding conflict caused multiple members to transfer to other American Families through national intervention. D’Anna’s own story is particularly interesting based on the small glimpse given to us by D’Arco.

Paolo D’Anna was unknown to Al D’Arco though D’Arco had been a made member for five years and an associate for even longer, but as a formality he was officially introduced to D’Anna because of D’Arco’s recent promotion to capodecina. As the man’s new representative in Cosa Nostra, Al D’Arco was obligated to meet Paolo D’Anna even though he was over 100-years-old and homebound. Angelo Bruno was recorded similarly telling an underling how elderly members were still expected to contact their captain once a month to retain their standing in the organization, as they might have relatives who needed representation from the Family even if the member himself was too old to concern himself with the active affairs of the mafia. D’Arco didn’t say if this monthly check-in was a rule in his Family, though at 103 we can be certain Paolo D’Anna didn’t have many months left to worry about these formalities.

As evidenced by the official introduction, formality still had some relevance when it came to D’Anna meeting his new captain. When Al D’Arco met the elderly Paolo D’Anna, D’Anna indicated he was inducted into Cosa Nostra back in Sicily, proudly showing Al D’Arco a photo of the man he reported to in his native Agrigento hometown. Paolo D’Anna’s story was typical of members from his generation and informs us about the relationships that formed the Colorado Family. Pueblo was not only linked to Sicily and other American cities but spread out relatively wide within its own Colorado jurisdiction considering its small size.

Though it was far from Wyoming, the Pueblo group had influence throughout the state of Colorado and this included the southern part of Wyoming, perhaps including the crime-friendly railroad town of Rock Springs. Rock Springs crime figure John Anselmi's son John Jr. went to a private school in Canon City, Colorado, just outside of Pueblo, where Family members Joe and Gus Salardino lived. Joe Salardino was identified by FBI informant Frank Bompensiero as the former underboss of the Pueblo Family and like the Anselmis, the Salardinos had close ties to Los Angeles as reported by Bompensiero. Hardly evidence of involvement with the Colorado mafia, but it demonstrates the criminal-minded Anselmis were no strangers to the immediate area around Pueblo, where the mafia leadership resided.

Influential Colorado Cosa Nostra member and future leader Rosario Dionisio was married in Wyoming in 1916. Additionally, the Smaldone brothers of Denver reportedly had connections across the border in Cheyenne, including bootlegging operations during their formative years. The Smaldones were Italian mainlanders with heritage in Basilicata’s Potenza province and their predecessor in Denver was a Calabrian, Giuseppe Roma, who was murdered in 1931. Though a direct tie-in can’t be confirmed, Rock Springs would have been an attractive Wyoming location for the illegal pursuits of these mafia figures and the northern part of Colorado brought mainlanders into the organization.

A missed connection comes from the Denver-based Clyde Smaldone. As one of the most publicized and active underworld figures in Colorado history, Smaldone is unsurprisingly carried as a member of the Pueblo-based Colorado Family. Along with his brother and other relatives, Clyde Smaldone was known publicly as a dominant Italian crime leader in Denver.

Many would assume Clyde Smaldone was a “boss”, and perhaps the Smaldones eventually claimed official titles, but Colorado is one among endless examples of appearances not fitting the reality inside the organization. Insider knowledge shows that Smaldone was formally a subordinate of Sicilian men who lived in the far south of the state. This takes nothing away from his presence in Denver, it is a simple fact within the organization.

Prior to Clyde Smaldone’s death he allowed his son to tape record him in interview sessions where he spoke openly about his former life; openly about his basic criminal past, but not Cosa Nostra. Smaldone’s son supplied the tapes to an author and an enjoyable book was written but there is little substance in terms of organizational information. If Clyde Smaldone was a made member, he didn’t break his oath or share the identities of made members in Colorado or Wyoming.

Smaldone did tell his son that early on in his “career” he traveled the country frequently, meeting many different men. This was left vague but didn’t seem to be framed around criminal activity. If he was inducted into Cosa Nostra we can be certain he traveled to the many documented meet-and-greets the early mafia held to make formal introductions and strengthen politics. His travels also could have taken him to Wyoming, where the Smaldones are known to have had criminal ties in Cheyenne.

Rock Springs is a significant distance from Cheyenne, but the Colorado Family was not afraid of distance. Boss Jim Colletti lived in Pueblo and ran his Colorado Cheese Business in Trinidad, 84 miles and over an hour south on modern highways. The co-owner of Colorado Cheese was Joe Bonanno, who shifted regularly between his homes in Arizona and New York. Colorado Cheese was initially a partnership between members of the Colorado and Bonanno Families and included the Trinidad-based Rosario Dionisio and other Bonanno members close to Joe Bonanno.

The Pueblo and Trinidad branches were the core of the organization and there was fluidity between them, making distance a fact of life even for the tightknit mafiosi from Agrigento in the southern part of the state. They were known to visit their Denver faction as well and some of them moved there. This is not unique to the Colorado Family nor are they a particularly strong example, as other Families had members, formal crews, and administration members in different states or across national borders. Colorado is simply one example among many.

The Colorado Family maintained a small formal organization with a wide geographic base, though by the time the FBI ramped up their investigation into Cosa Nostra during the 1950s and 1960s, the Colorado group appears to have been much like other small US Families in that its membership and activities were dwindling. Like the bosses of other Western Families who were caught in the fallout from the Apalachin meeting in 1957, Jim Colletti pulled back heavily from his activities and FBI informants from later years had little to report on with regards to Colorado’s national presence in Cosa Nostra politics.

There is no evidence the FBI ever developed a significant informant within the Colorado Family, making it virtually impossible to definitively identify most of its members regardless of era. Working knowledge of the Colorado Family is primarily limited to guesswork, relying on speculation and the public stature of a given underworld figure. As we’ve learned with more deeply-penetrated Cosa Nostra organizations, these external factors alone can’t be used to determine formal membership or rank within a given Family. We do have the identities of some members, though.