The Silinontes: Joe Bonanno's Secret Cousins

Castellammare del Golfo and Cosa Nostra connections in New York's Southern Tier.

New York Cosa Nostra boss Joe Bonanno is among the most well-known names in mafia history. Widespread coverage of the 1960s “Banana War” and autobiographies written by both Bonanno and his son Bill have given us a deep look into Joe Bonanno’s life, including the interconnected Castellammarese blood clans that produced him and many of his mafia peers.

New research has uncovered another set of biological Bonanno relatives who have gone unacknowledged by insiders and outsiders alike. Like virtually all of Joe Bonanno’s male relatives, these men were also involved in Cosa Nostra. Their surname is Silinonte but their story can’t be told with one name alone.

An Illegitimate Bonanno

An FBI report from 1967 shows future DeCavalcante Family captain Rudy Farone, not yet an inducted member, worked at a Brooklyn fish market owned by an obscure mafia associate named Carlo Silinonte. In addition to selling seafood, the men ran gambling operations out of the establishment along with Carlo’s older brother Stephen Silinonte. While investigating Rudy Farone’s mafia activities, the FBI interviewed Stephen Silinonte and learned their father Giuseppe Silinonte had been “very close” to Joe Bonanno, though the FBI would come to learn this was an understatement. It turns out the Silinontes were far more than ordinary "run of the mill" mafia associates.

Further investigation by the FBI revealed Carlo and Stephen's father Giuseppe Silinonte (1885-1964) was from Castellammare Del Golfo and a biological first cousin of Joe Bonanno. Though Stephen Silinonte denied any knowledge of Joe Bonanno’s mafia activities, he admitted his deceased father attended the 1956 wedding of Joe’s son Bill Bonanno to the niece of Joe Profaci, a contemporary of Joe Bonanno who ran his own Brooklyn Family. Another Silinonte son, first name redacted, confirmed the blood and social relationship between Giuseppe Silinonte and Joe Bonanno.

Giuseppe Silinonte’s son revealed his father was the illegitimate child of Joe Bonanno's paternal uncle and had been disowned but remained close to Joe Bonanno in New York City. Giuseppe Silinonte's father could be Giuseppe "Peppe" Bonanno, identified as a key mafia figure in an 1896 Castellammare murder investigation that included other familiar Castellammarese mafia surnames. Many of these names, including Asaro and Buccellato, would become fixtures of Cosa Nostra in the United States and Sicily. Men from these direct lineages remain active in both branches of the organization today.

Though he never personally met him, Joe Bonanno’s autobiography details his uncle Peppe’s influential role within the Castellammare mafia during this period. Bonanno described how his uncle became the representative of the Bonanno-Bonventre-Magaddino blood clan and carried significant political weight in the local organization, with Joe Bonanno’s father Salvatore succeeding his brother in this role when he was murdered by the mafia in the late 1890s. Peppe Bonanno’s alleged killers came from a rival Castellammarese mafia clan that showed up with him in the 1896 investigation, the Buccellatos. Giuseppe Silinonte was still a teenager living in Castellammare del Golfo at the time of Peppe Bonanno’s murder, though Silinonte would leave Sicily for the United States several years after these events.

Having arrived in the US in 1903, Giuseppe Silinonte was arrested in New York for Grand Larceny in 1915 after purchasing a stolen horse, wagon, and harness. After being found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison, Silinonte was released on good behavior after ten months. Silinonte found legitimate employment as a longshoreman, a profession he shared with many other Castellammarese mafia figures of the period. Castellammare del Golfo is a maritime community then as it is now and Sicilian immigrants fell into work that paralleled their experience back home. Silinonte’s cousin Joe Bonanno spent time in New York City with his parents during these early years before returning to Sicily until adulthood, but being just a boy at the time his relationship with Silinonte was no doubt limited to social or familial interactions at most.

By World War I, Giuseppe Silinonte was listed as living at 54 Floyd Street in Brooklyn. Research into this address shows the only 54 Floyd Street is today on Staten Island, but further investigation shows a historic Floyd Street existed near the Williamsburg and Bushwick neighborhoods of Brooklyn that has since been renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Place. The Bonanno Family and its Castellammarese membership originated in this area of Brooklyn and many of its early members resided in Williamsburg and Bushwick. Silinonte naturally fit into this environment given his background and relation to Joe Bonanno.

Silinonte and his growing family lived in New York City through 1920 but moved to Endicott in Western New York State’s Southern Tier by 1925, where there was already a faction of Castellammarese mafia figures near the Pennsylvania border later identified as members of the Pittston-based Cosa Nostra organization. Joe Bonanno himself did not settle in America as an adult until 1924 and spent time in Buffalo prior to New York, providing little if any overlap between the cousins in Brooklyn during the 1920s but Bonanno’s time in Buffalo put him in relative proximity with Endicott and the Southern Tier.

Two members of the Bonanno clan would live in Endicott during the 1930s while Silinonte was there, too. Stefano Magaddino’s elder brother Gaspare was living there in 1935 before following Stefano to Niagara Falls and Joe Bonnano's future in-law Joe Genovese was also among the Castellammarese mafiosi in the greater Pittston and Endicott area where he was a partner in fellow Castellammarese Joe Barbara's bottling company, Mission Beverage. Genovese’s son Gregory and cousin Frank, who went by “Joe” as well, were identified in the 1960s as Cosa Nostra members in the California Bay Area. Gregory Genovese would marry the daughter of Joe Bonanno.

Joe Barbara & the Politics of Endicott

Joe Barbara’s name is well-known because of the 1957 Apalachin meeting that ended in the arrests of national mafia bosses. Barbara was a close friend of his compaesano Joe Bonanno and the two men were among the most significant Castellammarese mafia leaders in America along with Bonanno’s cousin Stefano Magaddino, the Buffalo Family rappresentante. A photo in Joe Bonanno’s book shows him spending leisure time with Barbara.

A 1965 FBI recording of an embittered Stefano Magaddino indicates other mafia leaders deliberately excluded Joe Bonanno from the Apalachin affair held at Joe Barbara’s estate, what Magaddino termed “the mountain”, citing his cousin’s close relationship to law enforcement, though analysis of the FBI’s transcript suggests Stefano’s remark could have been in reference to another cousin, Peter Magaddino. Regardless, Joe Bonanno similarly claimed he did not attend the Apalachin meeting, citing his own disinterest and political preference. Bonanno was not among the long list of arrestees, though authorities rightfully suspected his involvement.

Joe Bonanno claimed he was staying in nearby Endicott where he met with his cousin Stefano Magaddino prior to the latter’s departure to the meeting. He also confirmed a meeting the year previous at Joe Barbara’s estate, this one a scheduled 1956 Commission meeting. Commission meetings were held every five years, a process confirmed by many sources, among them Bonnno and Magaddino both, and in his book Joe Bonanno criticizes the decision to hold an impromptu national meeting in the area so soon after the previous one. Bill Bonanno claimed to have attended the 1956 meeting with his father.

The Bonanno Family did have a confirmed presence at the 1957 Apalachin affair that cannot be objectively denied. Family representatives at the meeting included Joe Bonanno’s top capodecina Carmine Galante, underboss Frank Garofalo, and Bonanno’s uncle John Bonventre, a capodecina like Galante. All three men were Castellammarese and Carmine Galante was once a longshoreman in New York like Giuseppe Silinonte. There were Castellammarese Galantes involved with the Pittston Family in the Southern Tier area, too, one being Sam Galante whose degree of relation, if any, to Carmine is unknown. Joe Barbara’s mother was also a Galante.

Some sources indicate Joe Barbara was a New York State-based rappresentante of the Pittston Family, including FBI informant and Gambino capodecina Carmine Lombardozzi, who stated Barbara held this role until the end of his life. Lombardozzi was a 1957 Apalachin attendee, giving his word additional weight, but in another FBI interview Lombardozzi contradicted this statement and said Russell Bufalino was the Pittston boss at the time he attended Apalachin. Another informant, Joseph LaTorre, was the son of an old line Pittston leader and he told the FBI in 1955 that Bufalino was by then established as Family boss but answered to Joe Barbara in New York’s Southern Tier. Joseph LaTorre’s brother Samuel would later cooperate with the FBI himself and provided a succession of who he believed to be Family bosses but like his brother did not include Barbara on the list of men who held this specific rank.

A wider analysis of available information points to Barbara as a high-ranking member of another sort rather than the group’s rappresentante, perhaps holding an administrative rank like consigliere or even serving as capodecina to represent the Southern Tier of New York State. Most accounts suggest he was more than a captain alone, though, and there is evidence he was at least part of an internal ruling body that has been thus far overlooked by most public accounts of Cosa Nostra’s traditional structure. This role may provide better context on the true nature of his authority.

When the Family’s founding member Stefano LaTorre fell out of favor with retired Pittston leader Santo Volpe, LaTorre’s son Joseph told the FBI his father was the subject of a trial where Joe Barbara sat on a Family council to decide his fate. Volpe was identified by both of LaTorre’s sons as the Pittston boss followed by John Sciandra, with Russell Bufalino replacing Sciandra, suggesting Barbara’s status was somewhat different. These formal councils, often referred to in Italian as the consiglio and similar names, were common in the early Sicilian and American mafia and Families could elect a “chairman” or “secretary” who oversaw their council. The reference to Joe Barbara could indicate he held this role given he was said to have arranged Stefano LaTorre’s trial following the dispute with Santo Volpe.

These Family councils operated horizontally in the hierarchy and included a fixed panel of members comprised of the administration, captains, and sometimes senior members without rank. The formal participants in these councils dictated Family policy and presided over underworld trials, referred to as an arguimendo. The description of this Pittston council is consistent with descriptions of the formal consiglio in other Families and the members of these panels were officially designated and near-equal to the boss, which may explain confusion over Joe Barbara’s formal rank and Russell Bufalino’s somewhat subordinate role to him.

Based on examples in other Families, each consiglio member had a vote and was free to challenge the Family rappresentante in matters of opinion, with the council’s chairman having additional weight. In San Jose and Chicago the chairman even had the authority to facilitate the demotion of a boss and consult directly with the national Commission if needed. This chairman or secretary position was akin to the traditional Family consigliere and perhaps it was technically the same position given a chairman of the consiglio lends itself to the title of official consigliere based on language alone. Whatever his formal rank, Joe Barbara was without question the organization’s top leader in the Southern Tier of Western New York along the Pennsylvania border.

Many years after Joe Barbara’s 1959 death, his close aide Anthony Guarnieri in Binghamton was identified in a 1974 FBI report as the Pittston Family’s capodecina in New York’s Southern Tier, indicating continuity with Barbara’s previous stature in the area or a relative equivalent given Guarnieri didn’t have nearly the reputation of Joe Barbara. Anthony Guarnieri was an outlier in the Southern Tier group in that he had mainland heritage that contrasted with the Sicilian Trapani and Agrigento roots of the area’s core members, but his close relationship to Barbara brought him into the organization. Guarnieri was among the men who attended the 1957 Apalachin event, allegedly assisting the guests on Joe Barbara’s behalf.

Adding another dimension to the discussion, Philadelphia mafia historian Celeste Morello proposed a theory that Endicott once had its own distinct Cosa Nostra Family centered around the members’ Castellammarese heritage. Some national groups are more or less confirmed to have had multiple small Families based around hometown compaesani relationships, a mirror of their Sicilian origins as village- and neighborhood-based mafia organizations comprised of men from the same town. These smaller groups later joined with other nearby compaesani Families and formed what we now know as larger regional and city-wide American Families.

There is circumstantial evidence this process played out in various parts of the United States, including nearby Buffalo and affiliated crews like Utica. Member sources have identified multiple early Philadelphia and Chicago area groups who operated in close proximity before being pulled into one central Family, too, a reflection of early Americanization in the US mafia. This did not play out in every territory, where there is reliable information there was always one group or where multiple Families continued to exist, but this shift in certain locations likely assisted with national governance due to the exponentially larger geography of America compared to the small island of Sicily.

The Sicilian mafia itself adopted a similar system, dividing the island into what it called mandamenti (districts) made up of small nearby Families governed by an elected capomandamento from one of these groups. The various mandamenti then reported to a capoprovincia who presided over the entire province, with these higher-level representatives then forming an island-wide Commission, much like the American Commission. This appears to have solved political issues and created new ones, but ultimately simplified governance.

Though in Sicily the individual villages and neighborhoods retained their separate designation as Families within the mandamento, the net result was similar to these larger territorial Families in America, which were in stark contrast to individual Sicilian Families. Sicilian Families required as few as ten members to be formally recognized according to pentito Leonardo Messina from San Cataldo, the village neighboring Montedoro where the earliest Pittston leaders came from. Messina (b. 1955) claimed to have been a seventh-generation member in San Cataldo, so his ancestors overlapped with the founders of the Pittston Family in Sicily and this gives us insight into the Sicilian mafia groups that produced the organization. Carmine Lombardozzi told the FBI he believed the Pittston-Endicott organization to have approximately fifty members, a size equivalent to an entire multi-Family mandamento in rural Sicily.

This merging of American and Sicilian Families into larger bodies was not necessarily a sinister conspiracy to control other groups, but a political practicality based on geography and environment. The earlier governing bodies prior to the formation of the Commission, the Gran Consiglio and Assemblea Generale, apparently required representatives from each US Family to attend national meetings and the shift to larger regional groups reduced the number of representatives required and made national politics more convenient as American Cosa Nostra began to cement its permanent foundation in the country.

There were exceptions later on with regard to these large-scale meetings, the national Apalachin conference being a prime example, but this updated system of governance allowed the boss of this centralized regional Family to act as a “governor” over the territory rather than a group of competing “mayors” in small compaesani-defined Families. He was elected boss, though like a capomandemento it required a larger selection of factions to agree. The “governor” could then sit on the Commission himself if elected or report to a Commission member who represented him, following a similar but not exact process we see in Sicily today. This is my own interpretation, but it is based on observable traits in the evolution of American and Sicilian Cosa Nostra.

I’m inclined to support Celeste Morello’s perspective on Endicott, as the Southern Tier Castellammarese colony was in place shortly after the turn of the 20th century and already included men from mafia clans exhibiting the patterns we see in similar groups. The local chapter of the Castellammare del Golfo Society was heavily linked to men like Joe Barbara and other Cosa Nostra members. Barbara himself was among the wealthiest residents of the area and active in community affairs. We see these mutual aid clubs play a similar role in countless early American Families, most infamously the DeCavalcante Family’s Ribera Club, where the Family rappresentante also presided over the club’s activities. These clubs weren’t wholly criminal in nature, rather they were a reflection of a “society unto themselves” of which the local Family was a key part.

The heavily Castellammarese Bonanno Family in Brooklyn, as well as the other New York Families, were initially defined by neighboring compaesani groups before becoming pan-Sicilian and ultimately pan-Italian conglomerates. New York took a reverse route from what is seen elsewhere in the country, though, with at least two Families each splitting into two new groups, creating four total Families in addition to the fifth Family, the Bonanno Family. New York and New Jersey are exceptional in that it was the immigration gateway for most mafiosi after 1898 and thus had a massive influx of new members and recruits (especially during Benito Mussolini’s crackdown on mafia activity), requiring a different arrangement that allowed for more groups. Other parts of the country relied on a slower trickle of recruits based on compaesani-informed chain-migration and combining Families may have made more sense than division. Other factors, including conflict and political tension, contributed to this evolution as well.

Returning to the rest of America, even if my theory is wrong it is not baseless, as a decision had to be made early in American mafia history to have large regional Families that did not resemble their Sicilian origins. Yet this did not happen everywhere, as Families in the California Bay Area, Wisconsin, New Jersey, and the rest of Illinois outside of Chicago did continue to resemble their Sicilian counterparts more closely, never having been merged into one central political entity. Many of these Families remained primarily Sicilian, too. There is no question Endicott and New York’s Southen Tier belonged to Pittston by the time the FBI became aware of their activity, but they maintained traditional compaesani-based recruitment practices that may have roots in separate organizations, a pattern pointed out by Philadelphia member Harry Riccobene when discussing early Philadelphia groups during prison interviews.

If Celeste Morello’s theory about Endicott is true, Joe Barbara may have been a young rappresentante of this Castellammare-centric Endicott group before it merged with nearby Pittston, which was made up of compaesani from Caltanissetta province with their own distinct network. Certain Western Sicilian villages also provided a “leadership class” within the mafia network. Though countless cities and rural comuni alike generated members and leaders throughout the United States, specific strongholds tended to produce more bosses and high-ranking members than others and informants in Detroit and St. Louis stated this explicitly in context with Cosa Nostra politics. The Castellammarese are one of these “leadership classes”, with Castellammare-born rappresentanti appearing in major cities like New York City, Buffalo, Philadelphia, and Detroit even when this compaesani group was a minority faction within a larger Family.

Confirmation of Endicott’s autonomy as a distinct Family earlier in its history is yet to be found, but Joe Barbara’s age could have made him a successor to someone else who previously held a leadership position along the Southern Tier. Indeed, a fellow Castellammarese candidate several years Barbara’s senior does surface in the early 1930s. This man, Antonino Mistretta of Elmira in nearby Chemung County, was even a close associate of Joe Bonanno’s cousin Giuseppe Silinonte and will be discussed in more detail in the next section about Silinonte’s activities in Endicott.

Regardless of Endicott’s formal history, Joe Barbara maintained a role as defacto chief over his compaesani in the Southern Tier and he was a peer of American bosses from his hometown like Joe Bonanno (New York City), Stefano Magaddino (Buffalo), Salvatore Sabella (Philadelphia), and Gaspare Milazzo (Detroit). It can’t be forgotten either that FBI informant Carmine Lombardozzi of the Gambino Family believed Barbara to be a one-time boss of the entire Pittston / Endicott region and perhaps he was for a time even though there are discrepancies with sources who place Pennsylvania-based members from Caltanissetta in this role during the same timeline, including Lombardozzi’s other contradictory account of Russell Bufalino as boss during Apalachin. That Barbara hosted not only the 1957 Apalachin meeting but also a Commission meeting the year previous speaks to who he was nationally even if these meetings were held in his domain on behalf of a Pittston area rappresentante — not all attendees had to be bosses.

Joe Barbara continued in a senior role until the end of his life whether he was a “Pittston” boss or held earlier stature over a separate Southern Tier Family that was merged with Pittston. If such a merger took place it wouldn’t prevent Barbara from holding a rank of some sort in the Pittston group. Some of the men identified by longtime Philadelphia member Harry Riccobene as captains and influential members in his organization apparently held high stature in the earlier compaesani-based Philadelphia Families according to interviews Celeste Morello did with Riccobene and the same may be true of Barbara. Sicilian pentito Antonino Calderone’s account shows Sicilian bosses stepped down and were replaced sometimes without war or death while others ascended to capomandamento or capoprovincia, not unlike political service in American government. Ranks went up, down, and some men remained influential in the Family like a former statesman. This occurred in the United States as well even though the American mafia system evolved according to its own environment and they didn’t have the same system of provincial or district representatives but rather an elite group of avvocati (advocates) who sat on a single national Commission after 1931.

Outside of official positions and formal mafia affiliation, the Italian social and economic environment in Endicott and Binghamton revolved around Joe Barbara and his associates just as the local Cosa Nostra faction did and these relationships naturally connected to other national locations in the Castellammarese network. Joe Barbara’s business partner Joe Genovese became an extended relative of Giuseppe Silinonte when his son Gregory married the daughter of Silinonte’s cousin Joe Bonanno, though there was another possible connection between Silinonte and the Genoveses that will be referenced later, too. Gregory Genovese’s story is quite incredible on its own: he finished dental school in Los Angeles, married Joe Bonanno’s daughter, became a practicing dentist in the Bay Area, and was inducted into Cosa Nostra all in the same short window of time, ultimately becoming a San Francisco member.

Dr. Gregory Genovese attempted to get involved in local municipal politics with the encouragement of San Francisco boss James Lanza, though these attempts were curtailed by events outside of his control as a West Coast mafia dentist. Hardly a “gangster”, Dr. Gregory Genovese faced intense public scrutiny and federal pressure in the mid-1960s because of his father-in-law’s notoriety. He was also tormented by Cosa Nostra’s own governing bodies beginning in late 1964 when Joe Bonanno was deposed as boss of his New York Family. Bonanno went into hiding as the Commission made attempts to contact him, with the pressure of national mafia politics and government scrutiny both falling on Dr. Genovese’s back in the San Francisco Family.

Gregory Genovese was called to testify in government hearings during his father-in-law’s period of strife and reluctantly complied, though he did not break his mafia oath and denied knowledge of the organization. His testimony still provided valuable background about his blood family’s national friendships, nearly all of which fed into Cosa Nostra. Though he made no mention of ties with the Silinontes in Endicott, Dr. Genovese detailed in a court hearing how his family was deeply tapped into the local Pittston and Endicott mafia element during their time there, including relationships with leading figures from Castellammare del Golfo in addition to those from Caltanissetta province like Russell Bufalino, described by Stefano LaTorre’s son as another participant in the 1949-1950 trial of his father.

Russell Bufalino, the future Pittston boss who helped organize the Apalachin meeting, was employed with Joe Barbara’s bottling company while Joe Genovese was a stakeholder in the business. Joe Genovese would move to Arizona in the late 1940s where he transferred membership to the Bonanno Family. Joe Bonanno himself maintained a residence in Arizona beginning in the early 1940s and members subequently followed, gathering around his status as rappresentante. Bonanno was much like Joe Barbara in that local Castellammarese mafiosi orbited around him, though as a New York City boss Joe Bonanno was operating at a much higher scale in national politics and subject to the full volatility of his position. Joe Barbara in contrast presided over a much smaller fiefdom along New York’s Southern Tier in league with Pittston.

FBI recordings of New Jersey boss Sam Rizzo DeCavalcante meeting with Bonanno Family leaders revealed a discussion in which former Pittston / Endicott mafioso Joe Genovese was said to be a candidate for the position of capodecina over the Bonanno Family’s West Coast members after Joe Bonanno was removed from power during the early stages of what would become a protracted mafia war. The complaints registered against Bonanno — all violations of national mafia protocol and political in nature — were numerous and the last straw involved a personal conflict within the New York City Castellammarese faction. Though hometown and familial ties brought these men together, familiarity breeds contempt and Cosa Nostra occasionally leads compaesani and even relatives to oppose each other politically, with strategic violence making an appearance.

The DeCavalcante tape’s 1965 reference to Joe Genovese as a potential West Coast Bonanno capodecina is peculiar given the position he was in with his son’s father-in-law Joe Bonanno. Being related to Bonanno through the marriage of their children, it seems unlikely the new boss Gaspare DiGregorio could expect Joe Genovese to take on this role given the Arizona faction’s proximity and dedication to Joe Bonanno. Perhaps there were misgivings between the two in-laws or Genovese was expected to fall in line with the new administration as is mafia custom. There is no evidence this plan to promote Joe Genovese ever materialized and if it did, it was brief. The members there lost recognition in Cosa Nostra circles alongside their former boss and Genovese faded from view even as Joe Bonanno continued to push for reinstatement. Joe Genovese died of natural causes in 1982.

Giuseppe Silinonte died of natural causes the same year Joe Bonanno was officially removed from power and unlike Joe Genovese he was not living near Joe Bonanno on the West Coast. Whatever impact these significant political events would have had on him is null given he died with his cousin still serving as rappresentante of the New York organization. There may have been other relatives who were impacted, however, as this article will explore later. Regardless, Joe Bonanno’s problems in Cosa Nostra occurred 40 years after the Silinontes were established in Endicott, which is when Giuseppe Silinonte’s story picks up considerably. The Castellammarese men in New York’s Southern Tier were intertwined with Joe Bonanno and his cousin fit in perfectly.

Deportation Proceedings and Further Background

Giuseppe Silinonte was arrested in 1930 after his "giant" illegal alcohol still caught fire in Endicott. He was living in the front of the plant and told police it had only been operational for five days. It's unclear what became of the charges though he does not appear to have served significant jail time, if any at all, beyond the initial arrest. His young son Russell would also be arrested for bootlegging in the Endicott area in 1935. Joe Barbara’s bottling company may have provided a legitimate base for some of the extensive mafia-controlled bootlegging activities in the area, as these member-owned businesses offered resources and lawful coverage that masked illegal alcohol distribution.

Giuseppe Silinonte visited Canada twice in the early 1930s and experienced difficulty upon trying to re-enter the US in 1933 due to a lack of identification confirming his immigration status in the United States. Silinonte is also documented as having returned from Canada in 1931 and his involvement with a large alcohol still in 1930 may have played a role in his travels. Mafiosi were frequently engaged in bootlegging operations across the border and Bonanno Family boss Salvatore Maranzano, Joe Bonanno’s Castellammarese mentor, owned property in Ontario where he spent time prior to his 1931 murder. Sicilian pentito Dr. Melchiorre Allegra identified Maranzano as the capoprovincia of Trapani province in the 1920s prior to arriving in the US and becoming a Family boss and capo dei capi, his stature in Sicily no doubt informing his eventual rise to power in America.

Giuseppe Silinonte’s entry point back into the United States was in Massena, NY, which is closer to Montreal. Silinonte’s return from Canada in 1931 came less than a month after Salvatore Maranzano’s September 1931 murder and Salvatore Maranzano was known to have connections in Montreal, where his relatives allegedly stayed during the Castellammarese War. If Silinonte was an inducted member of Cosa Nostra, the timing of his travels may have had a political connection to the murder of Bonanno Family boss and capo dei capi Maranzano.

Giuseppe Silinonte was allowed back in the United States despite his 1933 border troubles but he would undergo seven years of deportation hearings stemming from the combination of his previous larceny conviction and an accusation that he entered the US illegally. The extended nature of these proceedings was likely the result of later events that will be explored in-depth in the next section. The deportation hearings were a valuable source of information on Giuseppe Silinonte, as they highlighted aspects of his background that were later shared with the FBI in the aforementioned interviews with Silinonte’s sons.

At a 1941 deportation hearing, Giuseppe Silinonte confirmed he was an orphan born in Castellammare and said the Silinonte surname was given to him by municipal authorities in Sicily. Silinonte is a variation of Selinunte, an ancient Greek city whose ruins are in Castelvetrano, Trapani. It was common for authorities to assign a predetermined surname to orphans and the Silinonte/Selinunte name appears to have cultural significance in Trapani province. Joe Bonanno described spending his childhood playing in similar Greek ruins in Castellammare del Golfo, the remnants of a city called Segesta.

Giuseppe claimed during his deportation proceedings that he didn't know his official surname was Silinonte until applying for an Italian passport before heading to the US. He claimed to have used the name Giuseppe DiGirolamo for his entire life up to that point, DiGirolamo being the name of his foster parents. A later Bonanno member who ended up on the West Coast, Vincent “Jimmy Styles” DiGirolamo, had Castellammarese heritage and once hid Castellammare Family leader Gaspare Magaddino out at his home in the 1960s, Magaddino being the first cousin of Stefano in Buffalo and therefore another relative of Joe Bonanno. I’m unable to confirm if Jimmy DiGirolamo was a relative of Giuseppe “DiGirolamo” Silinonte’s foster family but Jimmy was among the men who remained loyal to Joe and Bill Bonanno after they fell from power in New York. The deportation proceedings made reference to two other surnames used by Giuseppe Silinonte in addition to DiGirolamo and multiple spellings of Silinonte, these being “Muffoletta/Muffoletto” and “Monte”.

In 1945 Silinonte was pardoned and had his earlier larceny conviction cleared from his record. Proof of his original legal entry into the US was found which stopped the deportation proceedings. Though his relation to the Bonannos was not mentioned in the deportation hearings, the connection was clearly known to him given his sons knew him to be a close friend and cousin of Joe Bonanno.

Giuseppe Silinonte married his wife Angela Ciaravino in Brooklyn in 1907, though she too descended from his hometown of Castellammare del Golfo and arrived to the US the same year he did. One of the naturalization witnesses was a Vito Genna, there being Castellammarese Gennas with Cosa Nostra membership in Sicily and New York. Angela Ciaravino Silinonte’s background may have more significance when considering her husband’s blood relation to Joe Bonanno, as the Ciaravino name was the maiden surname of Castellammarese Buffalo boss Stefano Magaddino's mother as well as that of Joe Bonanno’s successor, Gaspare DiGregorio. Magaddino and DiGregorio’s mothers were sisters.

Joe Bonanno was a biological cousin of both Giuseppe Silinonte and Stefano Magaddino, making the latter two men relatives as well. It's significant that despite his orphan upbringing Silinonte appears to have married a woman connected to the Bonanno-Magaddino clan of which he is a blood relative. Intermarriage among cousins and extended relatives was the norm within this insular group, possibly even for an orphan like Silinonte as evidenced by his marriage to a Ciaravino. Sebastiano “Buster” Domingo, who briefly rose to prominence in the Bonanno Family alongside Joe Bonanno under Salvatore Maranzano in the 1930s, also had ties to a branch of Ciaravinos.

Ciaravinos from Castellammare were active in a 1920s Illinois-Michigan mafia war, where this set of Ciaravinos and their relatives the Domingos fought local rivals in a bloody bootlegging conflict. This group included the aforementioned Buster Domingo of Castellammarese War fame, who would move to New York City and participate in multiple wartime murders before becoming an early captain under Joe Bonanno. Domingo also served in Bonanno's wedding party before Buster’s own 1933 murder and is pictured in a photograph in Joe Bonanno’s autobiography. Additionally, the Domingos were related to early Bonanno captain Vito Bonventre, murdered in 1930, an extended relative of Joe Bonanno and Stefano Magaddino who Bonanno indicates served as capodecina over Salvatore Maranzano before Maranzano’s rise in stature. Though lesser known than other Castellammarese mafia surnames, Silinonte's wife's surname of Ciaravino is evidently well-connected to the dominant mafia clans of Castellammare del Golfo.

Giuseppe Silinonte’s fellow Southern Tier Castellammarese, Joe Genovese, provides another substantial link to the above names. In addition to Genovese’s son marrying the daughter of Joe Bonanno, Joe Genovese’s maternal aunt was married to Vito Bonventre, the capodecina mentioned in the previous paragraph. Joe Genovese's own wife was a Ciaravino like Giuseppe Silinonte’s wife, indicating Silinonte was related to Genovese on multiple fronts. Joe Genovese and his wife were also maternal cousins, showing blood as well as marital relation played a role in these arrangements. The interrelation between all of these men is constant and pervasive when examining the roots of the Castellammarese family tree.

In addition to her maiden name being Ciaravino like the relatives of other Castellammarese mafiosi in the United States, Giuseppe Silinonte’s mother-in-law’s own maiden name was Galante. Joe Barbara’s mother was a Galante and other mafia-connected Galantes were present in New York’s Southern Tier, as noted earlier. Whether a degree of relation existed between Silinonte’s wife and Endicott’s Cosa Nostra faction or for that matter other interrelated civilians in the area, the Silinonte couple moved to a community where they could easily blend in with compaesani.

Giuseppe Silinonte's involvement with Castellammarese mafiosi was not limited to circumstantial and familial connections. Though no associates were named in Giuseppe and son Russell Silinonte's respective bootlegging arrests in the 1930s, the Silinontes were no strangers to the Southern Tier mafia faction. This is evidenced by a widely-publicized double murder case that dominated the lives of the Silinontes in the 1930s and 1940s.

The Van Cise Murders

In 1936, Giuseppe Silinonte and his son Anthony were charged with the 1932 double murder of the elderly Van Cise brothers on a remote farm outside of Elmira, NY. Allegedly a robbery gone wrong, 25-year-old Anthony Silinonte was initially arrested in 1934, released, then brought back in for questioning. Police interrupted Anthony Silinonte's wedding procession to bring him in for his second interrogation, tuxedo and all. Anthony was later re-arrested in 1936 and convicted in 1937, being sentenced to death.

Arrested with Anthony Silinonte for the Van Cise murders in 1936 were Endicott mafia figures Bartolo Guccia and the Elmira-based Antonino Mistretta. A non-Italian from New York City named Constantine "Gus Alexis" Alexopolis and another Italian named Onofrio "James Ross" Coraci were also charged in the plot. “Alexis” was Greek while Coraci was said to be from Sicily, the latter having lived in New York’s Southern Tier for many years before eventually moving to Rochester.

Both Bartolo Guccia and Antonino Mistretta were from Castellammare del Golfo like the Silinontes and the Mistretta surname shows up even today in the Bonanno Family. In fact, a 2020 Italian investigation into today’s Castellammare Cosa Nostra Family revealed a current Bonanno member named Antonino Mistretta met in Sicily with Castellammare boss Francesco Domingo to request a favor. The investigation identified Domingo as a relative through marriage of early Bonanno boss Salvatore Maranzano, his aunt having been married to Maranzano’s son Mariano. Francesco Domingo himself likely descends from a shared lineage with Buster Domingo though it cannot be confirmed at this time. The Bonanno Family network and its sister organization in Castellammare del Golfo includes countless recurring names among its generations of mafiosi, so the existence of an Antonino Mistretta among the Southern Tier mafia faction of the 1930s is one “rhyme” among many.

Like Joe Bonanno’s in-law Joe Genovese, Bartolo Guccia was a close associate of Southern Tier mafia leader Joe Barbara and Guccia attended the ill-fated 1957 Apalachin meeting at Barbara's estate. Along with Barbara and other Castellammarese New York State-based Pittston members, Guccia was active with the local Endicott branch of the Castellammare del Golfo Society, a compaesani mutual aid group. Bartolo Guccia served as a committeeman for the statewide conferences held between the different New York branches of the club.

Fellow Southern Tier mafioso and Apalachin attendee Emanuele Zicari from Siculiana, an apparent outlier from Agrigento, was another part of this statewide committee and influential Buffalo member Paolo Palmeri, from Castellammare, was the chief speaker. The Buffalo and Brooklyn Castellammare del Golfo Societies included local Castellammarese mafia members among their ranks just as the Endicott branch did. Had it not been for the notoriety of the Apalachin event, Guccia would be hidden far deeper in mafia obscurity but he was tapped into the core of the national Castellammarese network as evidenced by the few occasions he raised his head.

Under cross-examination during the Van Cise trial, Bartolo Guccia said he knew Antonino Mistretta "back in the old country" and claimed Mistretta was the only co-defendant he knew aside from the Silinontes. Bartolo's brother Antonio Guccia testified he also knew Mistretta in Sicily and worked for him in an operation that sold illegal alcohol along the Southern Tier. Antonio Guccia worked the counter in an establishment that distributed Mistretta’s alcohol.

Bartolo Guccia's attorney stated Guccia came to the US at age 17 in 1908, first living in Endicott before moving to New York City and Philadelphia, ultimately returning to the Southern Tier where he became a business partner with Giuseppe Silinonte in a local speakeasy. It was also revealed Guccia was arrested on a gun charge in Brooklyn in 1915, the same year Giuseppe Silinonte was arrested in New York for Grand Larceny. The attorney claimed Guccia and Silinonte had a falling out over their speakeasy business in 1928 and their friendship fell apart. Nonetheless, he admitted Guccia and the Silinontes were living on different floors of the same house for several years leading up to the trial.

It was mentioned Bartolo Guccia also lived in Niagara Falls sometime between 1928 and 1932 where he ran a restaurant before returning to Endicott. Note that all of the areas Guccia was said to live (Endicott, NYC, Philadelphia, Niagara Falls) had influential Castellammarese mafia colonies. Guccia’s mother was a Milazzo, a surname shared with powerful Castellammarese mafioso Gaspare Milazzo, a former Brooklyn-based Bonanno Family member who was murdered in 1930 after becoming boss of the Detroit Cosa Nostra Family.

Giuseppe Silinonte was named as another participant in the double murder of the Van Cise brothers and charged alongside his son and associates, though Giuseppe became a fugitive and successfully evaded arrest. Anthony Silinonte allegedly confessed following his 1936 arrest, telling authorities his father recruited him for the planned robbery. He described how Bartolo Guccia impulsively shot one of the Van Cise brothers to death when the victims attempted to fend off the robbery, killing the second Van Cise brother as well before escaping.

The younger Silinonte said the Castellammarese men went through the pockets of the victims and took money from the murder scene which was then split between the participants. Anthony also identified his father Giuseppe as having fired a gun during the murders. Anthony later recanted his confession but it contributed to his own conviction. A separate trial would be held for the other men, not including the fugitive Giuseppe Silinonte.

A prosecution witness during one of the trials, Joseph Spagnolio, ran a local nightclub where he knew Giuseppe Silinonte, Bartolo Guccia, and Antonino Mistretta to spend time. He said the three men were involved in alcohol trafficking and supplied the club with liquor, but Spagnolio had told them not to hang around due to their underworld reputations. Joe Spagnolio said the men nonetheless went to the club after the Van Cise murders and told him it was the Greek “Gus Alexis” from NYC who tipped them off that the elderly Van Cise brothers kept a large amount of cash in their farmhouse.

Joseph Spagnolio quoted Giuseppe Silinonte as saying the Van Cise brothers were killed after the two victims tried to physically attack his son Anthony during the robbery. Spagnolio was not without his own criminal background, a fact defense attorneys attempted to spin in their favor. While serving a prison sentence in the 1920s, Spagnolio assaulted two inmates with an iron bar and received an additional ten years. Spagnolio tried to petition Antonino Mistretta for help getting out of prison.

Charges were dismissed against “Alexis” due to lack of evidence and the trial for the other three remaining defendants resulted in a hung jury. Guccia, Mistretta, and Coraci were retried which resulted in acquittals for all three men. Following these trials, the still-incarcerated witness Joe Spagnolio was able to escape from prison following a jailbreak. Giuseppe Silinonte remained a fugitive during the court proceedings against his son and associates, with his own trial awaiting him should he be detained.

The investigation into the Van Cise murders revealed Antonino Mistretta (b. 1898) of Elmira was a figure of some importance in Chemung County to the east of Endicott in Broome County and Apalachin in Tioga. Mistretta was the only defendant most of the co-defendants and witnesses admitted to knowing, with the Guccias claiming a relationship with him in Castellamamare in addition to working under his bootlegging operations in New York’s Southern Tier. It became evident during the trial that the Van Cise robbery was organized under Antonino Mistretta's direction or supervision.

As noted, prosecution witness Joe Spagnolio sought out Antonino Mistretta to help him get out of jail in the 1920s and testified it was Mistretta he contacted about keeping underworld figures away from the nightclub due to the attention they attracted. Mistretta also provided bond for a female witness who committed perjury. Mistretta’s name has never come up elsewhere but he has the markings of a significant mafia figure in the Southern Tier during this period. If Philadelphia historian Celeste Morello’s theory is correct that Endicott once had its own Family, Mistretta may have been the rappresentante or perhaps a capodecina if the Southern Tier group belonged to Pittston by that time. Antonino Mistretta died in 1947 before the age of 50, still a resident of the Southern Tier, making him a likely Pittston member in his final years and a possible early predecessor to Joe Barbara.

Giuseppe Silinonte evaded authorities for four years and was finally detained in Brooklyn in 1940. His cousin Joe Bonanno was at this time the boss of the heavily Castellammarese Cosa Nostra Family centered in the Williamsburg and Bushwick neighborhoods of Brooklyn. It’s unknown what role Silinonte’s connection to the Bonanno Family played during these events, though his connections to the group are self-evident based on his blood and compaesani relationships as well as his previous residence on historic Floyd Street. One of Silinonte’s sons told the FBI his father was “very close” to Joe Bonanno, making it highly likely the New York boss and his associates assisted the illegitimate Bonanno cousin when he fled to Brooklyn.

A hat found at the Van Cise murder scene was linked to Giuseppe Silinonte, the size of the hat and hairs found inside of it matching Silinonte, and he was put to trial in 1941. However, a decision was made soon thereafter to indefinitely suspend the elder Silinonte's first degree murder charge as authorities were confident he would be deported as a result of his ongoing deportation proceedings that ran simultaneous to the murder case. During the deportation hearings, US authorities learned Italy would refuse to receive Giuseppe Silinonte should he be deported so the US planned to keep him in a detention camp in the interim. A newspaper article describing this scenario noted Silinonte would likely face a hostile climate under Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Italian government, noted for its harsh persecution of mafia figures.

As mentioned earlier, these proceedings were dropped when they found documentation of Silinonte's legal entry to the US. It doesn't appear authorities pursued the Van Cise murder charge against Silinonte after it was suspended. The erroneous deportation proceedings were an unexpectedly lucky break for Silinonte despite causing him seven years of grief.

Giuseppe's son Anthony Silinonte filed for appeal immediately following his 1937 conviction and was sentenced to die at Sing Sing later the same year, but he was declared legally insane in late 1937 and transferred to Dannemora. Like Sing Sing, prison facilities in Dannemora carried out executions. The 1940 census shows Anthony Silinonte was still serving in Dannemora and he is recorded as dying in Dannemora in 1944 at age 33, perhaps indicating his execution was eventually carried out. Records cannot be found to confirm the exact nature of his premature death but among the perpetrators he served as the lone martyr in the Van Cise murder case.

Return to New York City

The drawn out Van Cise murder trials and the death sentence of Anthony Silinonte likely contributed to the Silinonte family's decision to permanently return to New York City. They were the subject of widespread media attention in the Southern Tier area for years due to the Van Cise case. The investigation additionally exposed the involvement of Giuseppe Silinonte and his associates in bootlegging and shined a light on his underworld connections in Endicott and surrounding areas.

Documentation shows Giuseppe Silinonte living back in Brooklyn by 1942 near the Gowanus / Park Slope area. Silinonte had been staying in Brooklyn on the lam until 1940, but with Silinonte's murder trial being dropped the year previous he no doubt had the freedom to “officially” return to Brooklyn. By this time many figures with roots in the Castellammarese colony in Williamsburg and Bushwick had migrated to other areas of New York but Silinonte’s choice to settle around Gowanus / Park Slope still placed him in relative proximity to his earlier residence on Floyd Street. Records show he had been in that part of Brooklyn since at least 1938 and back in New York he continued to work as a longshoreman.

Giuseppe Silinonte traveled abroad in 1951, presumably to his native Sicily, though his destination can't be confirmed. Despite Silinonte’s involvement with Castellammarese mafia figures in Endicott and close relationship with Joe Bonanno, Giuseppe Silinonte has never been identified as a member or associate of his cousin’s Family. That is not true for two of Silinonte’s sons, however. In addition to the involvement of Giuseppe's sons Carlo and Stephen Silinonte in a fish market and gambling activities with future high-ranking DeCavalcante member Rudy Farone, Stephen and his brother Russell were identified as Bonanno members in an early 1960s FBI report.

Carried by the FBI as Russell and Steve "Silononti", numerous records confirm Giuseppe Silinonte had a son named Russell (1917-1999) in addition to the elder Stephen (1908-1975). As with his father, the younger Silinonte brother Carlo (1927-1997) has never been publicly identified as a Bonanno member or associate despite his mafia association with brother Stephen. His close association with Rudy Farone could indicate he was on record with the DeCavalcante Family, though that too is unconfirmed. Carlo did have several arrests in the late 1960s, including illegal weapon possession and promoting gambling.

Russell Silinonte's underworld activities go back to Endicott, noted earlier, where he was arrested on a 1935 bootlegging charge during his late teenage years. It can be assumed Stephen was also active in illegal activity in Endicott given the documented criminal activity of his father and two younger brothers, including the doomed Anthony who took the brunt of the Van Cise murders. The FBI’s investigation into Carlo and Stephen Silinonte’s association with Rudy Farone revealed general information about the Silinonte brothers, including their involvement in the seafood business, another throwback to Castellammare del Golfo’s maritime element as evidenced by their father’s profession as a longshoreman.

In addition to owning the Rex Fish Market on 5th Avenue in the Gowanus / Park Slope area of Brooklyn, Carlo Silinonte and his brother Stephen ran a social club on the same street called the Oceanside Boys Club. The FBI learned Giuseppe Silinonte owned the building that housed the club and ownership of the property passed on to his family following his 1964 death. The Oceanside Boys Club carried Giuseppe Silinonte’s sons as members along with their associates. The FBI learned DeCavalcante associate Rudy Farone was not simply an employee but a co-owner of the Rex Fish Market with the Silinontes.

Through the FBI’s interview with Stephen Silinonte, they learned Stephen had been a longtime employee of the New York State Housing Authority and retired in 1966 due to ill health. He was on disability and earned a stipend from the government. Stephen Silinonte denied any knowledge or involvement in Cosa Nostra, but did tell the FBI that associate Rudy Farone was someone he could go to for assistance when he didn’t want to involve the police. He stated Rudy Farone would know who to contact to help resolve the matter if Farone couldn’t solve the matter himself. Rudy was at this time years away from his initiation into Cosa Nostra but Silinonte’s description indicates Farone held higher stature than Stephen Silinonte himself, raising doubt as to Stephen’s alleged membership in the Bonanno Family. Despite Stephen Silinonte’s relative openness with the FBI it should be noted Silinonte was not an informant and his statement may have been deceptive or otherwise intended to misdirect attention away from himself.

Another FBI interview with a redacted son of Giuseppe Silinonte, not Stephen or Carlo, revealed this brother worked as a truck driver and served in the military from 1943 to 1946. Like his brothers Stephen and Carlo, this Silinonte brother admitted to being a member of the Oceanside Boys Club and told the FBI he was an avid golfer. He admitted to having “heard of” DeCavalcante Family capodecina Frank Cocchiaro as well as future Colombo Family boss Carmine Persico, then a capodecina. However, the redacted Silinonte brother said he did not personally know Cocchiaro and Persico despite admitting familiarity with their names.

Frank Cocchiaro and Carmine Persico both had crews active in the same area of Brooklyn where the Silinontes lived and Cocchiaro was a mentor to their associate Rudy Farone, by this time proposed for membership in the DeCavalcante Family. Farone was close to Colombo Family members in the area, though the FBI learned he did not get along with Carmine Persico. Among other young associates groomed by Frank Cocchiaro in the years to come was Bill Cutolo, who would be released from the DeCavalcantes and become a high-ranking Colombo Family member before his 1999 murder that imprisoned Carmine Persico’s son Allie Boy for life. Certain Brooklyn neighborhoods showed close cross-pollination between not only the DeCavalcante and Colombo Families but evidently the Bonannos as well.

It’s possible the redacted brother in this second FBI interview is Russell Silinonte. However, there was at least one other living Silinonte brother, Joseph Jr., who to my knowledge has not been identified as a mafia figure. Regardless, Russell undoubtedly operated in the same circles as his brothers given he was identified by an unknown FBI source as a Bonanno member like elder brother Stephen and all of the Silinontes were members of the Oceanside Boys Club owned and operated by the brothers. Russell Silinonte’s involvement in Endicott bootlegging at an early age provides an easy assumption that he maintained underworld relationships in Brooklyn alongside his brothers.

The Silinonte brothers were acquainted with Cosa Nostra figures in the Gowanus / Park Slope neighborhoods and their father’s presence there as far back as 1942, when the family returned from Endicott, tells us Giuseppe Silinonte was himself part of this mafia environment and influenced his sons’ lifestyle, much as he recruited Anthony for the ill-fated Van Cise robbery-turned-murder with Bartolo Guccia. Though the elder Silinonte’s early residence near Williamsburg and Bushwick placed him in the Bonanno Family’s ground zero, by the time he returned to New York City the organization had filtered into many other neighborhoods and the Bonanno Family had Castellammarese members and associates distributed throughout the New York metropolitan area.

Beyond one FBI source identifying Russell and Stephen Silinonte as Bonanno members, nothing is known about their involvement in Bonanno Family activities. Though Stephen Silinonte agreed to an FBI interview, he did not reveal anything incriminating about himself or his relatives beyond his father’s connection to Joe Bonanno and investigation into the brothers focused on ties to the DeCavalcantes and Colombos. Circumstantial evidence is not always a surefire indicator of formal Cosa Nostra affiliation, but the alleged Bonanno membership of two sons, a close blood relation to Joe Bonanno, and his own mafia activities with the Castellammarese in Endicott make it likely Giuseppe Silinonte was a Bonanno member after returning to NYC. If he was in fact a Bonanno member, Silinonte’s 1885 birth places him before the cusp of most known Bonanno members and his advanced age would have made later sources less familiar with him and easy to overlook.

It should be emphasized that early Cosa Nostra Families in New York were not constrained by geographic territory nor their social or business relationships, but primarily hometown and kinship. Bonanno Family membership was historically defined by heritage from Sicily’s Trapani province, particularly Castellammare del Golfo. With few exceptions, Castellammarese mafia members in New York City and New Jersey belonged to the Bonanno Family, especially when said members were related by blood and marriage to the leadership, as the Silinontes were.

Though Giuseppe Silinonte’s 1964 death removed him from the Bonanno war intrigues later that year, his sons were identified in the aforementioned FBI report as possible members at the time and would have been impacted by the massive upheaval inside and outside of the Bonanno Family if indeed they were affiliated with this organization. Naturally many blood and marital relatives of Joe Bonanno were central to the dispute, but most rank-and-file members and associates were also knocked off balance by Bonanno’s removal from power and the years of conflict that followed. That the names of the Silinonte brothers don’t appear to surface on the many FBI recordings of Cosa Nostra members discussing these events during this time indicates they did not become directly involved more than was required and were not politically relevant, be they members or associates.

Jumping forward to another period of upheaval, Stephen Silinonte was deceased by the time Apalachin attendee Carmine Galante claimed authority in the Bonanno Family in the late 1970s. After taking power, Galante reinstated and promoted a number of men who were initially loyal to Joe Bonanno during the Bonanno conflict, including some members who were shelved on the West Coast. Russell Silinonte was still alive at this time and if indeed he was a Bonanno member as one source indicated, he was perhaps the last remaining Bonanno blood relative in the organization under Carmine Galante’s defacto leadership. Galante was certainly in a position to know who Russell Silinonte was and Carmine’s travels to New York State’s Southern Tier in the 1950s are well-established though the Silinontes left the area the previous decade.

The Castellammarese Carmine Galante came up in the organization under Joe Bonanno, remaining fiercely loyal to his mentor, suggesting he was familiar with the Silinontes given Giuseppe Silinonte’s close relationship to his cousin. Carmine Galante was also a former longshoreman like the elder Silinonte and during his time as capodecina in the 1950s Galante had members in nearly every New York borough along with New Jersey, Montreal, and even Upstate New York, giving him a unique range of relationships in the organization. If Carmine Galante had contact with Russell Silinonte during the years before Galante’s 1979 murder, however, there is no indication of it in contemporary FBI files. The FBI did receive information that Carmine Galante was in contact with Joe Bonanno via telephone in the months before his death but the extent of his relationship with New York relatives like the remaining Silinontes is unknown.

The Silinontes’ alleged Bonanno Family affiliation opens up a question related to their brother Anthony's death sentence and possible execution in 1944. Bonanno Family boss Joe Massino, who presided over the family between 1991 and 2005, is alleged to have told new Bonanno members how a fellow Bonanno figure was sentenced to death and executed at some point earlier in the organization's history but researchers have had difficulty confirming this story. Many Italian criminals were executed in New York State during generations past, but available records give no indication any of them were connected to the Bonanno Family.

It's worth considering that Joe Massino's story is a reference to Anthony Silinonte. He was a criminally-active brother of two rumored Bonanno members and his father was a first cousin of Joe Bonanno, plus Anthony was Castellammarese. This story could have evolved via verbal storytelling into a "Bonanno member" being executed, especially if it originated from within the Castellammarese element who would have seen Anthony as one of their own regardless of his formal affiliation.

Though the Silinontes were likely associated with the Pittston Family or a separate Castellammarese Endicott group at the time he was sentenced to death, we can't rule Anthony Silinonte out as a made member there prior to his 1936 arrest, especially given he participated in a 1932 double murder and four years would pass before his final arrest. Murder served as a common entry point in the early mafia and men of his age and younger were regularly recruited into the organization then, especially those from established mafia clans. Regardless of who, if anyone, Joe Massino was referring to, Anthony Silinonte is the only condemned individual I’ve discovered with a direct connection to the Bonanno Family.

Joe Massino cooperated in late 2004, wearing a hidden microphone to capture other incarcerated members until early 2005 while still holding the boss title. He has testified publicly once, with the transcript of his testimony serving as a valuable crash course in high-level mafia politics and recent Cosa Nostra history. Though he was given freedom following his cooperation, Joe Massino has not followed his earlier predecessor Joe Bonanno in doing public interviews or writing a memoir. Members who cooperated reported how Massino expressed contempt for Bonanno’s late-life decisions though his opinion may have changed since cooperating with the FBI — something Joe Bonanno never officially did.

There has yet to be an opportunity to find out how Joe Massino heard of this condemned Bonanno member or if he had any idea who it was. Massino was the sitting boss at the height of his power when Anthony’s brother Russell Silinonte died in 1999 and if Russell was still part of Bonanno Family circles he likely had some familiarity with Silinonte in name if nothing else given he was boss of the Family. Administration of a Cosa Nostra group involves carefully monitoring who members are and when they die, as the New York and New Jersey Families have a finite number of slots in their membership ranks and thus must inform other Families when they replace a deceased member, carrying the names of proposed and deceased members side-by-side on lists that are distributed to other Families for approval. Joe Massino’s cooperation also showed him to be familiar with a wide range of Family members and associates even when he did not have a close relationship to them.

If Russell Silinonte was a Bonanno member or associate as the 1960s FBI source indicates, it would be interesting to know if other Bonanno members knew him to be a direct relative of the former boss who produced the organization’s public name. The older Castellammarese element likely knew of the relation given it doesn’t appear to have been a total secret in these circles, though there were only traces of that generation left by the 1990s. If Anthony Silinonte was the condemned mafioso referred to by Joe Massino there was certainly one individual who could have shared that information with the Bonanno Family prior to 1999: Anthony’s brother Russell. However, this theory is speculative at best and requires far more evidence to be realistically entertained.

Giuseppe Silinonte died in 1964 and was joined by his wife the following year. Stephen Silinonte would live in East Farmingdale, Long Island, after leaving Brooklyn prior to his own 1975 death. Castellammarese Bonanno members were connected to East Farmingdale and nearby areas of Long Island spanning decades, many of them ex-Brooklyn residents too, among them Joe Bonanno. Bonanno maintained a home in Hempstead along with his residence in Arizona prior to being deposed as boss. Other Silinonte brothers stayed put, though, Carlo Silinonte dying in Brooklyn in 1997 and Russell Silinonte’s burial taking place in Brooklyn, suggesting he remained there as well prior to his own 1999 death.

Though Stephen Silinonte's death likely predates the active knowledge of Bonanno Family members who cooperated in the early- and mid-2000s, a period of mass-defection, these cooperating witnesses could have been aware of Russell Silinonte given he was alive until 1999. Russell, however, has not been mentioned by modern sources as a Bonanno member or associate, though naturally our public view into the Bonanno Family is not comprehensive nor do informants and witnesses know or recall every member who was alive during their time. The obscurity of the Silinontes is perhaps appropriate given they originated as an illegitimate branch of the Bonanno tree, not being fully recognized even within their own lineage and their Cosa Nostra status left vague to outsiders.

Final Thoughts

Whether or not Russell and Stephen Silinonte were made members as the 1960s FBI report alleges, the information collected in this article makes it obvious they were not randomly thrown on a list of Bonanno members. The Silinonte brothers were Joe Bonanno's first cousins once removed and their father was born in Castellammare del Golfo and involved in murder, robbery, larceny, and bootlegging, recruiting his son Anthony into violent crime in collaboration with other Castellammarese mafia figures in the Southern Tier. Russell was a former bootlegger in Endicott and Stephen associated with DeCavalcante and Colombo figures in Brooklyn alongside younger brother Carlo.

Carlo Silinonte was tapped into Cosa Nostra activities, though he has only been referenced as an associate. He co-owned a fish market with a future DeCavalcante capodecina and the two men were involved in both legal and illegal activities. He ran a social club with his brothers on property owned by his father Giuseppe and the location served as their headquarters. Carlo’s own association with mafia figures is further indication of the ongoing history this family had with Cosa Nostra and shows crossover specifically between men involved with the Bonanno and DeCavalcante Families.

I'm not surprised most Bonanno informants and witnesses make no mention of the obscure Silinontes, but it's surprising Joe and Bill Bonanno never make a single reference to the Silinontes in any of their books, especially given Stephen Silinonte's admission of their close relationship. This is true for Joe Bonanno especially, as he talked extensively about his relatives from Castellammare and gushes over the reputation of his murdered uncle Peppe Bonanno, who may have been the biological father of Giuseppe Silinonte.

The Bonannos however go to great lengths to distance themselves from the "dishonorable" aspects of their life. Giuseppe Silinonte was the illegitimate child of Joe Bonanno's uncle, being abandoned at birth, and may have been an inconvenient figure in Bonanno's story. Silinonte obviously didn't fit into Joe Bonanno's tailored narrative about the Bonanno clan's devotion to family, honor, and responsibility. Joe Bonanno’s autobiography is titled A Man of Honor and though it is an excellent resource it is blatantly self-serving.

Carmine Galante wasn’t a relative of the Bonannos, but he was one of their closest associates at the peak of Joe Bonanno’s power. Yet Carmine Galante is barely mentioned by Joe and Bill Bonanno in their memoirs. Galante was a convicted narcotics trafficker, violent killer, and notorious malandrino, making the reason for his omission fairly obvious. Joe Bonanno similarly omits (or wasn't aware of) his uncle Peppe's association with goat thieves in Castellammare del Golfo and connection to the murder of an innocent estate guard in 1896, instead glorifying Peppe Bonanno as a "man of honor" and one-time leader of the Bonanno-Bonventre-Magaddino clan in Sicily. In addition to Giuseppe Silinonte’s illegitimate birth, the Bonannos may have wanted to distance themselves from the Silinontes due to the media attention given to Anthony Silinonte's double murder conviction and death sentence.

A question I can't answer is how Giuseppe Silinonte managed to find his blood relatives and become involved with key Castellammarese mafia figures despite being abandoned immediately after birth. He testified at his deportation hearing that his biological parents gave him up three days after being born and he feigned ignorance of them, yet he seems to have followed the exact same path he would have followed had they raised him within the Bonanno clan as a legitimate son. That Silinonte’s foster parents’ surname of DiGirolamo surfaces in the Bonanno Family via the Castellammarese “Jimmy Styles” DiGirolamo allows us to consider that Giuseppe Silinonte’s adopted family was not without its own connections, peripheral or not.

Silinonte was nearly twenty years older than his cousin Joe Bonanno, so his involvement with the mafia could well predate Bonanno's own. Giuseppe Silinonte was living in New York City when Joe's father Salvatore Bonanno lived there, opening up the possibility he had contact with his biological father's brother during his formative years in New York. Joe Bonanno was with his father in New York as a boy before returning to Castellammare, eventually returning as a young adult and going full-force into Cosa Nostra.

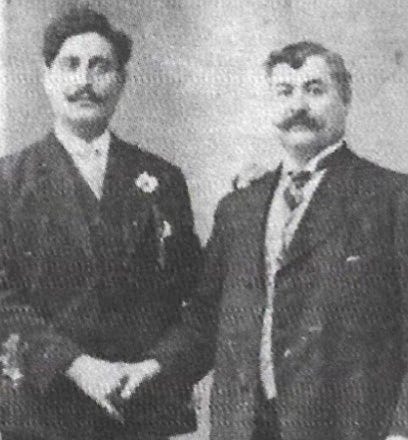

Salvatore Bonanno’s association with influential members of the organization that would bear his son’s name is evident from a photo in Joe Bonanno’s book of his father posing with Salvatore Saracino, a leading New York Castellammarese member linked to other influential names of the time, among them Ignazio Lupo and Giuseppe Morello. Saracino was said to be a relative of the Domingos, noted earlier for a relation to the Ciaravinos, the maiden name of Giuseppe Silinonte’s wife. The close-knit compaesani network and its many connection points place the elder Silinonte deep inside this New York Castellammarese colony regardless of who raised him. It's not a question of "if" but "how" Silinonte originally connected with the Bonanno mafia clan that refused to officially claim him.

It’s highly probable that the tight mafia community in Castellammare del Golfo was well-aware of Giuseppe Silinonte's true origins and maintained ties to him even if the nature of their blood relationship was quieted. Peppe Bonanno’s stature in the Castellammare Family in the 1890s may be significant as well if he was Silinonte’s biological father. Shared surname or not, Giuseppe Silinonte was part of a local mafia aristocracy and illegitimacy did not prevent a relationship between Giuseppe Silinonte and his mafia relatives like Joe Bonanno. This type of arrangement isn't uncommon for illegitimate births even outside of Cosa Nostra, it just happens this one occurred in a very specific environment and subculture.

My own mother was born illegitimately, never properly knowing her biological father. Her birth mother raised her, but she had no relationship to her father yet lived in the same town and was told general information about his background. Growing up in St. Joseph, Missouri, my Mom was taken to visit an older lady known only to her as “Mrs. Sherman”. Mrs. Sherman doted on my mother and they corresponded until Mrs. Sherman died decades later. I have letters she wrote to my Mom asking for updates about my sister, by that time recently born. It was never acknowledged, but Mrs. Sherman was my Mom’s paternal grandmother and a relationship existed between them.

There are other examples of mafia members having second families and in some cases the children are illegitimate, not taking on their father’s name while remaining involved in their father’s life — personally as well as within Cosa Nostra. Colombo Family member Greg Scarpa had an illegitimate son who was an associate of his crew prior to being murdered. More significantly, former Genovese boss Vincent “the Chin” Gigante had an illegitimate son with the surname Esposito who was recently identified as a high-ranking member within the Genovese Family. There are numerous photos of Gigante and his son Vincent Esposito together with Esposito’s half-brother Andrew Gigante escorting their father to and from court. Giuseppe Silinonte shows that this took place within the Bonanno clan as well to some degree.

This story of illegitimate mafia scions joining the Family tradition makes for compelling fiction, too. This was a key narrative in the dramatic script to the third Godfather film. Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo didn't know who Giuseppe Silinonte was when they wrote the Godfather III, where the illegitimate son of Sonny Corleone becomes involved in the mafia under his uncle Michael, but the story of Giuseppe Silinonte proves illegitimacy and adoption isn't necessarily a barrier when it comes to real mafia blood clans either.

Giuseppe Silinonte represents one of countless "unknown unknowns" in Cosa Nostra history who would otherwise never come up for public discussion, a reference to his true origins being buried in a decades-old FBI report. Research has turned him into a “known unknown” — we know he exists, we know the circles he traveled in and some of the underworld activities he participated in, but the full extent of his status and involvement in Cosa Nostra are still left to the imagination. Through several separate pieces I was able to connect Silinonte to the mafia and Joe Bonanno, but it all began with one small lead that on its own seemed inconsequential. It turns out this lead opened up another side of the Bonanno clan we otherwise wouldn't have known about. It’s not the only “dishonorable” secret the Bonanno clan kept from public view, but it is a unique part of Joe Bonanno’s own story that has thus far been overlooked.

-

Thank you to “Chaps” for providing Rudy Farone’s FBI files.

Additional thanks to Griffin Orlich for assistance clarifying details related to Silinonte’s early Brooklyn residence and information on “Jimmy Styles” DiGirolamo. He also helped obtain one of the photographs of Giuseppe Silinonte.

I lived on the same block as Carlo Silinonte in the 1970s. He was married to Eileen, they had children Joseph, Stephen and Karen. I was friends with all 3. Nice family, I don't believe anyone had a clue as to this information.

Fabulously in depth and well written article. I have been compiling information regarding another figure mentioned in this piece for nearly the entire 38 years of my life... it hasn't been easy, but every few years I discover another piece to a seemingly fantastical story that was my great grandfather's actual life.... strangely enough, I bear the same name as, yet another person mentioned in this story, my great great uncle... and, although I was misled and flat out lied to about my relatives "lifestyle" choices, seems the apple doesn't fall far from the tree, in my case which I believe is why I am so determined to put the full puzzle together, although I know that when I do I will likely have to keep with the undeniable wishes of my predecessors, to keep it between my ears.... best of luck to you, and your much closer to understanding things than the fbi ever has been, I'll give you that for free....