The Mafia's Congressman in East Harlem

Another US politician with alleged Cosa Nostra membership surfaces, this time in New York City.

This article serves as a companion piece to an earlier article about US Senator Louis Boschetto, identified by an FBI member source as a rumored mafia member in Wyoming. For introductory information on formal relationships between historic Cosa Nostra and politics, the Boschetto article provides deeper context and cites examples of known politicians who have been brought into the mafia as made members. That article also attempts to provide in-depth analysis of the ways in which Cosa Nostra operates as its own political “state” comprised of representatives who follow protocol that is local, national, and sometimes international.

This article focuses on new information that alleges another American politician gained membership in Cosa Nostra. The original source of this information was cited in the original publication of the previous article on Louis Boschetto but an additional report has been obtained that provides further clarification and the information has been removed from the Boschetto article and reappropriated here. Though I speculated previously that this second reference to a mafia politician referred to the Wyoming Senator like the first source did, it is now evident a different man in New York City was being referred to and he is the focus of this piece. He can be directly connected to the highest levels of at least two New York Families in addition to leaders in Chicago.

If the account of his membership is true, this politician’s status in Cosa Nostra is a significant revelation about politics in New York City that also greatly impacts our understanding of its local mafia organizations. The background and ideology of this individual draw back to an old cliche: he was a complicated man. With that in mind, he was also a microcosm of two complicated organizations of which he was just one part: the US government and Cosa Nostra.

Senators & Congressmen

San Jose Family member and FBI informant Salvatore Costanza reported that former Wyoming Senator Louis Boschetto was a member of Cosa Nostra who maintained contact with Bay Area mafia figures. Though Louis Boschetto was an unlikely and seemingly random name in a strange location, Costanza identified Boschetto using his full name, political office, and place of business, indicating he was a regional mafia contact in Western Wyoming, this information coming to the informant from another San Jose member with whom Costanza was close. Boschetto was likely affiliated with the Pueblo Family in nearby Colorado but the extent of his involvement in mafia affairs is unknown and he was ostensibly legitimate albeit in a remote area known for a small but relatively active underworld and decades of political corruption involving Boschetto’s Democrat Party.

Louis Boschetto was not the only one of his kind, as John D’Arco and Fred Roti of Chicago were made members who served as high-level elected officials, but a reference from another California mafia member and FBI informant reported his own rumors of a US Senator or Congressman inducted into Cosa Nostra in New York. The source, Frank Bompensiero of San Diego, was among the most knowledgeable and generous members to cooperate with the FBI, breaking down the organization’s inner workings from 1967 until 1977 when he was executed by the Los Angeles Family he belonged to. Bompensiero had contacts with high-ranking members throughout the country and his decade of cooperation showed the range of Cosa Nostra’s national network even as it was dwindling in scope.

Like the Louis Boschetto reference from Salvatore Costanza in San Jose, Frank Bompensiero does not appear to have met this mafia politician himself but made two references to him as a member without identifying the man by name. During an early 1967 interview near the beginning of his cooperation, Bompensiero told the FBI that this US Senator came from the “State of New York” and believed he served two terms in office but would be 90-years-old if still alive. He declined to name the senator due to his perceived age, seemingly trying to protect the man from legal scrutiny. Confidential Informants, unlike Cooperating Witnesses who testify, are not required to reveal everything they know and though the FBI gently pressures them to reveal more details they are often content with any information a top-echelon informant is willing to provide.

In a follow-up interview with the FBI several months later, Bompensiero reiterated his belief that a high-level politician was a New York mafia member but amended his earlier assertion after “thinking it over,” believing this individual may have been a US Congressman rather than a senator. He referred again to the man’s advanced age and retirement from office though this time claimed to have forgotten the name. He knew Los Angeles member Aladena “Jimmy” Fratianno to have more knowledge on this figure, suggesting Bompensiero received the information from Fratianno, and told the FBI he would ask Fratianno for a reminder of the politician’s name when he next met with him. There was no follow-up specifically related to Fratianno on this matter in available reports from Frank Bompensiero’s cooperation.

Jimmy Fratianno was a former capodecina like Bompensiero and he was well-connected to cities like Cleveland, Chicago, and New York. Fratianno descended from the Italian mainland before living in Cleveland during his youth, while Frank Bompensiero was born in Milwaukee to parents from the area around Bagheria in Palermo province, a Sicilian mafia fiefdom that produced a majority of Wisconsin members. Around the time Bompensiero informed the FBI about this mysterious mafia politician, Fratianno was engaged in a trucking interest in Utah.

US Senator and alleged Cosa Nostra member Louis Boschetto's home of Rock Springs was near the Utah border and his contact with Bay Area members, where Fratianno was known to visit, led me to wonder if the former politician in question was not in New York as Bompensiero believed, but perhaps a closer eastern state: Wyoming. It appeared reasonable to speculate that Jimmy Fratianno made contact with Louis Boschetto during his time in the Mountain States, reported it to Frank Bompensiero, and Bompensiero in turn mistakenly told the FBI the man was from New York given the tendency for small details to be misreported within the mafia's game of telephone. A phrase like “out east”, for example, could become “New York” over time.

Frank Bompensiero was not, in fact, referring to Louis Boschetto. A report previously unknown to me reveals that the FBI spoke with Bompensiero about "his" US Senator or Congressman not two, but a total of three times. In the two previous interviews, Bompensiero confirmed that this man was a made member but did not reveal significant identifying information, only stating that he was very old and retired from political service. The reference came up initially when Frank boasted about Cosa Nostra inducting legitimate and respectable professionals, among them Dr. Gregory Genovese, a practicing dentist in the California Bay Area. It was apparently a point of pride to Bompensiero that his secret society included this class of member and indeed the history of Cosa Nostra, especially in Sicily, included politicians and professionals who have been identified by numerous sources as members and often even official leaders.

Though his initial revelation was vague, Frank Bompensiero finally opened up in the third interview, telling the FBI this mafia politician in New York was named "Marco Antonio". It was not Jimmy Fratianno who reminded Frank Bompensiero of the man's name, but rather other members of the Los Angeles Family who had a long history in the New York area, the LiMandris. Marco LiMandri and his son Joe were well-connected mafia figures in New York and New Jersey prior to moving to California and joining the Los Angeles Family in San Diego alongside Bompensiero.

A retired drug trafficker and bootlegger in his mid-70s by the time Bompensiero spoke with him, the elder LiMandri was likely already a member on the East Coast who transferred membership upon establishing residence in California during the 1940s. Bompensiero consulted with this former New Yorker when clarifying details about "Marco Antonio's" mafia membership, Marco LiMandri obviously ignorant of Bompensiero’s duplicitous purpose. Though inquiries of this nature are often frowned upon, Bompensiero was an esteemed former capodecina and multi-murderer who easily avoided suspicion through the early part of his FBI cooperation due to his long history in the organization.

Marco LiMandri, from San Cipirello in Palermo province, was tied to the mafia’s upper crust in New York City. He was both a cousin and brother-in-law of Gambino member Michael Pecoraro, who would also settle in California. LiMandri’s mother was a Pecoraro and he married Marianna Pecoraro, sister of Michael. Michael and Marianna Pecoraro’s father Giovanni had been a top Cosa Nostra leader in the Morello Family prior to its split into what are now two separate groups, the Lucchese and Genovese Families.

Giovanni Pecoraro was born in Piana dei Greci, though his son was born in San Cipirello, and Giovanni was a cousin of Morello Family boss Salvatore Loiacano from Marineo in addition to the LiMandri relation. Loiacano was murdered in 1920 while the elder Pecoraro was killed in 1923, both men slain in connection with volatile events within Cosa Nostra’s own political system as former capo dei capi and Family rappresentante Giuseppe Morello began to reassert influence after a long prison sentence for counterfeiting. The entry of son Michael into the Gambino Family instead of the Lucchese or Genovese Families could have been a result of Giovanni’s violent death.

Marco LiMandri and wife Marianna Pecoraro once witnessed the 1916 marriage of future Lucchese boss Bonaventura "Joe" Pinzolo to the sister of Giuseppe “Joe” Riccobono, a prominent New York mafioso from Palermo believed to have descended from a long line of Cosa Nostra members that continues today in the Gambino Family. Pinzolo was from Caltanissetta province and first arrived to Pittston, where neighboring compaesani created the local Family, and he was an ally of Genovese leaders Joe Masseria and Giuseppe Morello, Pinzolo being murdered by the Tommaso “Tom” Gagliano faction in 1930 during the Castellammarese War. Gagliano’s group resented Pinzolo for siding with the Masseria-Morello faction and usurping the position of Gaetano “Tom” Reina, a Corleone compaesano of both Gagliano and Morello killed earlier the same year.

Though it’s believed Marco LiMandri was already a member in the New York area, I have yet to see confirmation of his formal affiliation prior to Los Angeles. His relationship to Joe Riccobono and cousin/brother-in-law Michael Pecoraro’s membership in the Gambino Family suggests he belonged to them, though his ties to the Lucchese Family were equally strong. Along with his father-in-law having been a top member of the Morello Family, LiMandri witnessed Joe Pinzolo’s marriage and he had other association with Lucchese figures. Overall, though, it is apparent Marco LiMandri was close to important members wherever he happened to be at any given time.

As a resident of New Jersey by the 1920s after leaving New York City, LiMandri was allegedly linked to local mafiosi, including Tony Riela of the Newark Family who joined the Bonannos when the Newark group disbanded. Riela was from San Giuseppe Jato, a town that overlaps with Michael Pecoraro’s hometown of San Cipirello. The mafia in both San Giuseppe Jato and San Cipirello once had absolute control over municipal politics, many Cosa Nostra leaders serving as mayors and town councillors. Riela’s alleged “uncle” Vincenzo Troia and his relatives controlled San Giuseppe Jato, some of them holding local office, and Troia ultimately brought his mafia stature to Newark where he was killed in 1935.

Marco LiMandri associated with Settimo Accardi of the Newark Family in addition to Tony Riela, Accardi later serving as the Lucchese Family’s capodecina in New Jersey. A marital relative of LiMandri’s cousin/brother-in-law Michael Pecoraro, Bill Molinaro, was involved with the mafia in Cleveland and New Jersey, becoming an FBI informant. Molinaro told agents in 1958 about Marco LiMandri’s involvement with Accardi and Riela in alcohol and narcotics distribution.

LiMandri’s residence in New Jersey and involvement with Newark Family members could make that group another landing spot for his East Coast membership but again it is difficult to identify the exact Family he was assigned to, assuming he didn’t transfer between more than one during the mafia’s volatile years that accompanied his move from New York to New Jersey followed by his father-in-law’s violent death in 1923, then the break-up of the Newark Family in 1937. The Newark members were distributed among various New York Families and the entry of his associate Settimo Accardi into the Lucchese Family draws back to Marco LiMandri’s earlier connections to that organization. After a 1942 narcotics arrest with members/associates of the Gambino and Genovese Families, LiMandri moved to California and joined the Los Angeles Family when the Lucchese-linked Ignazio “Jack” Dragna was still rappresentante and the LiMandris would establish close connections to other West Coast figures who had a history with the Lucchese Family.

Marco LiMandri’s son Joseph, a made member, married into the Dippolito family of Los Angeles who descended from Baucina, Palermo. The Dippolitos previously associated with the Lucchese Family in New York where they were involved in criminal activity with Lucchese members the LoCascios from nearby Bolognetta. Charles Dippolito and son Joseph weren’t made until moving to California but became part of the Los Angeles Family leadership, Charles holding the title of consigliere during the leadership of boss Frank Desimone while Joseph Dippolito became underboss to Desimone’s successor Nick Licata. The Dippolitos provide another tie-in between Marco LiMandri and the Lucchese Family and show the LiMandris to be interrelated with top leaders in Los Angeles just as they were in early New York through Giovanni Pecoraro.

In addition to their apparent familiarity with a New York politician within Cosa Nostra, the LiMandris were tapped into local politics in San Diego as well. The Italian Civic Association League was founded by San Diego-based Los Angeles mafiosi and included relatives of Los Angeles Family members among its officers. Marco LiMandri’s other son John, not a Cosa Nostra member himself, was president of this organization and its purpose was to curry favor with local politicians with regard to legitimate business ventures under the local mafia’s umbrella. Frank Bompensiero’s brother Salvatore was another figure active with the Italian Civic Association League.

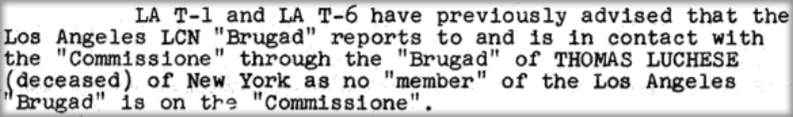

The LiMandris did not cut ties with the New York area after moving to Los Angeles. Frank Bompensiero told the FBI in 1969 how the politically-connected John LiMandri was associated with an unidentified New York banker who could assist the Los Angeles Family with illegal stock market activity. Bompensiero also reported information about Marco LiMandri independent of the allegations about the US Congressman in which he described LiMandri traveling to New York City for a visit and carrying underworld messages back upon return. In one instance, Marco LiMandri was updated on the status of the conflict-ridden Bonanno Family during his stay on the East Coast and he was given information to pass on to the Los Angeles Family about how to handle interactions with members of the disgraced Bonanno group.

Marco LiMandri was a true insider in New York-New Jersey and California mafia circles and his ties to members of consequence in the Gambino and Lucchese Families, including the old Morello organization, likely informed his knowledge of the New York politician referred to by Frank Bompensiero as a mafia member. Interestingly, the FBI reported Bompensiero’s conversation with the LiMandris immediately following an update Frank provided about the current status of the Lucchese Family leadership in the aftermath of Gaetano “Tommy Brown” Lucchese's natural death in 1967. It’s unknown if Frank spoke with the LiMandris about the Lucchese Family but the reference to mafia politician “Marco Antonio” is in the same small section of the FBI interview.

Adding credibility to Frank Bompensiero's claim about “Marco Antonio” is that he reported it to the FBI on two previous occasions then consulted with the LiMandris before finally providing this mafia politician's name to authorities in August 1967. Apparently Bompensiero had discussed this man with Jimmy Fratianno at an earlier time as well, adding a fourth Los Angeles member into the gossip mill given Frank spoke with both Marco LiMandri and his son Joseph about the congressman. There was no known New York politician at this time nor earlier with the name "Marco Antonio", though there was a man with a similar name: Vito Marcantonio, a former multi-term Member of the US House of Representatives from New York.

Further research indicates Frank Bompensiero was certainly referring to Vito Marcantonio and simply separated his surname of Marcantonio into the full name “Marco Antonio” or the FBI otherwise misunderstood the phrasing. Marcantonio was known by the nickname “Marc”, making it more likely his first name could be misunderstood as “Marco”. Unlike Louis Boschetto, Vito Marcantonio was a well-known national figure and his ties to underworld figures are also more evident than those of the Wyoming Senator.

Marcantonio's Mafia Association

One discrepancy between Frank Bompensiero's account of "Marco Antonio" and Vito Marcantonio is age. Though Marcantonio was indeed finished with politics by the time Bompensiero made his apparent reference to him, Vito was not elderly — he was dead. Having left the New York House of Representatives in 1951, Vito Marcantonio died of natural causes in 1954. Had Marcantonio been living in 1967 neither would he have been 90-years-old as Bompensiero speculated, but identical in age to Frank himself, 61 going on 62.

Frank Bompensiero did not personally know Vito Marcantonio and was relaying organizational gossip from other Cosa Nostra members, so he may have been unaware of Marcantonio's passing and true age up to that point. Frank admitted himself he was not sure if the man was still alive. Bompensiero lived in San Diego and spent time in prison during the latter half of the 1950s, making him less likely to know the current status (or lack thereof) of a New York politician who like him was a formal part of the mafia. It was not a common practice to update other Families and especially ordinary members about the natural death of a random mafia figure in another city barring personal connections so this much is not surprising. Despite Bompensiero's ignorance of Marcantonio's age and mortality, his account is supported by Vito Marcantonio's patterns of association. Like Bompensiero’s “Marco Antonio”, Marcantonio had irrefutable ties to Cosa Nostra.

Born in East Harlem in 1902 to parents from Potenza province in Basilicata on the Italian mainland, Vito Marcantonio grew up in an environment dominated by the early Cosa Nostra organization led by Giuseppe Morello from Corleone, the first known capo dei capi and Family boss of a mafia organization that later split into the Lucchese and Genovese Families. East Harlem was a breeding ground of mafia association and in these cross-pollinated Italian neighborhoods some of the first known relationships were formed between conservative Sicilian mafiosi and mainland Italian criminals, their on-and-off ethnic rivalry soothed by a shared affinity for Southern Italian underworld philosophies. There is no evidence suggesting Vito Marcantonio was involved in organized criminal activity as a youth but he grew up near the center of it and would have witnessed it all around him.

By the time he was eighteen, Vito Marcantonio pivoted from the tough tenement streets of Upper Manhattan, becoming involved in labor activism and corresponding political movements. Campaigning first for presidential candidate Parley Christiensen of the Farmer-Labor Party in the 1920 election, within four years he was campaign manager for congressional candidate Fiorello LaGuardia and the two men formed a close relationship. Marcantonio became a lawyer after graduating from New York University the following year and worked for LaGuardia’s firm while preserving a socialist outlook informed by his experience with labor advocacy as a teenager, eventually moving on to other law practices more suited to Marcantonio’s far-left views. LaGuardia himself represented the Republican Party but favored some socialist policies during the years he mentored young Vito, the two men being arrested together in 1926 for picketing at a dress factory strike.

Ironically, Fiorello LaGuardia is known for his strong opposition to organized crime during his early years as New York Mayor. Elected in 1934 following his departure from the New York House of Representatives the previous year, LaGuardia presided over the controversial prosecution of Salvatore “Charlie Lucky” Luciano in 1935 and condemned Frank Costello’s slot machine empire. Costello served as acting boss and eventual successor to Luciano, both men leading the Genovese Family. The Corleone-born Giuseppe Morello previously helped capo dei capi Joe Masseria run the same Family after Morello’s release from prison in the early 1920s and Luciano replaced Masseria as rappresentante when the latter was killed in 1931. Giuseppe Morello was murdered in 1930 but half-brother and one-time Genovese capodecina Ciro Terranova was regarded as “the Artichoke King” in the press for his control over said industry and Mayor LaGuardia began heavily regulating artichokes in the mid-1930s allegedly due to Terranova’s stranglehold over the trade.

What impact Fiorello LaGuardia’s anti-mafia efforts had on Vito Marcantonio’s relationship with Cosa Nostra is unknown. There is no reason to believe LaGuardia’s opposition to organized crime and racketeering was insincere but mafia politicians have a history of being two-faced, making it difficult to determine if Marcantonio and to some degree LaGuardia were overtly acting against Cosa Nostra while covertly making concessions to them. Elected officials and even one historic judge with formal membership in the Sicilian mafia have publicly condemned their confratelli while operating in accordance with them secretly, perhaps a necessity to avoid accusations of collusion. Baron Niccolo Turrisi Colonna, who served as a senator and Palermo Mayor, famously wrote an 1864 pamphlet exposing what he termed “the sect” and described the contemporary mafia of his era. Turrisi Colonna’s closest ally also happened to be Palermo boss Antonino Giammona and there were rumors of the Baron’s own membership in the organization.

Though these seemingly contradictory relationships can work in favor of both the politician and his underworld affiliates, sometimes an elected official strays too far from Cosa Nostra’s interests and the dilemma is solved through violence — mafia politicians are valuable but occasionally expendable. Examples of mafia politicians shrewdly (and dangerously) navigating their double life applies not to Fiorello LaGuardia so much as Vito Marcantonio but it does complicate the mayor’s story. LaGuardia's time on the New York House of Representatives and service as New York Mayor has made his name known internationally, the local airport even taking on his name in tribute, but his friendship with Marcantonio greatly assisted the younger man’s rise as a formidable politician despite LaGuardia’s own anti-crime stance and later evidence of Marcantonio’s association with Cosa Nostra.

Vito Marcantonio continued to support Fiorello LaGuardia's political efforts into the early 1930s before pursuing his own political career. Working first as an assistant US attorney, Marcantonio ran for congress in 1934 on behalf of the Republican Party like his mentor LaGuardia and following his successful election he served on the US House of Representatives until 1937. As an elected official, Marcantonio maintained his support of radical leftist causes and kept a strong presence in East Harlem where he was actively involved in local community outreach. His election as US Congressman paralleled LaGuardia taking the mayorial seat and this term was bookended on both sides by James Lanzetta, a Calabrian-American who preceeded and succeeded Vito Marcantonio as the East Harlem congressional representative.

Vito Marcantonio and Fiorello LaGuardia may have strayed from one another to some degree after Marcantonio rose to political prominence in his own right. LaGuardia spoke out against a 1937 Labor Day parade held in Madison Square Garden and dispatched police to monitor the event, of which Vito was one of the principal organizers and advocates. The rally descended into chaos and broke into a riot as police backed by the New York Mayor clashed with activists, Marcantonio leading the charge. He was roughed up by police and arrested during the melee but released due to his position as a sitting US Congressman, making anti-police statements in the aftermath. The year previous, in 1936, Vito Marcantonio had been arrested for ordering the beating of an apparent rival named Sol Silver but the charges were dismissed as with the 1937 riot.

Despite the 1937 Labor Day incident, later evidence suggests Vito Marcantonio and Fiorello LaGuardia maintained an amicable relationship into the 1940s and the men had a common interest in worker advocacy although they occasionally approached the subject differently. Authorities received information in 1940 about the Chicago branch of the Communist Party recommending that followers offer “full support” to LaGuardia given his favorable relationship with Marcantonio. The report describes how the New York Mayor had “always gone along with” Vito, indicating any tension observed on the surface was not indicative of what transpired between the men behind closed doors. American politics are theatrical and differences of opinion cannot be used to accurately understand these complex relationships, just as Vito Marcantonio’s political life tells us little about his relationship to Cosa Nostra.

Vito Marcantonio’s sympathy with Communism was well-known and led to intense scrutiny from authorities concerned with the ideology’s influence over American politics. Marcantonio denied being a member of the Communist Party when asked, but informants reported he was in fact a member and his patterns of association show him to be acquainted with important figures in the movement. He advocated for adjacent causes and served as an advisor to Communist-linked labor unions. Today he remains a celebrated figure among adherents of far-left political philosophies, especially as it relates to American history.

During his two-year absence from office after the end of his first congressional term, when James Lanzetta served again as East Harlem Congressman, Marcantonio switched his affiliation from Republican to the American Labor Party and subsequently attained re-election to the House of Representatives under this new banner. Serving this time from 1939 to 1951, Marcantonio was a unifying force in East Harlem, drawing supporters from different political backgrounds, social classes, and ethnic groups, Puerto Ricans in particular. Among the allies Vito Marcantonio made in Manhattan were high-ranking mafia members who shared his East Harlem roots.

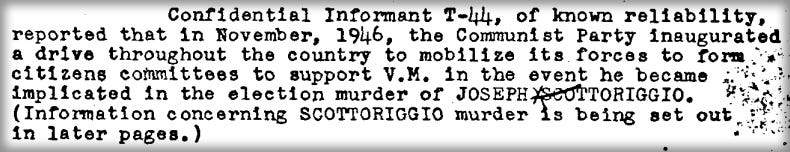

In 1946, Republican functionary and election captain Joseph Scottoriggio was beaten to death while attempting to monitor voter fraud at an East Harlem polling station and Genovese Family capodecina Mike Coppola was suspected of orchestrating the beating. The culprits reportedly did not intend to kill Scottoriggio but he succumbed in the hospital after refusing to cooperate with law enforcement. Future Lucchese consigliere Vincent Rao from Corleone also had rumored links to the incident and both Coppola and Joseph Rao were detained in connection with the murder but never charged; this Joe Rao was likely the Genovese member who belonged to Coppola’s crew. Scottoriggio was a political enemy of Vito Marcantonio working on behalf of rival candidate Frederick Ryan and it was believed Coppola interceded on Marcantonio's behalf.

Mike Coppola’s wife Doris allegedly overheard her husband’s plot to violently stifle opposition to his friend Vito Marcantonio though she died after giving birth to a daughter shortly thereafter, escaping law enforcement pressure to testify against her husband and his political allies after spending a period in hiding. The initial plot was allegedly hatched at Coppola’s home, said by an informant to be “a block away” from Vito’s office on 116th Street in East Harlem. Coppola’s residence and Marcantonio’s headquarters were only a short distance from countless locations relevant to Genovese and Lucchese Family history.

Hoodlum Emilio Tizel was kept in protective custody due to information he provided about the incident though it isn’t known what he shared with authorities beyond identifying Mike Coppola and Joseph Rao’s involvement. One informant, possibly Tizel, said that Coppola and Rao did not carry out the murder themselves but were responsible for ordering the incident at Vito’s request, with Mike Coppola’s underlings carrying out the deadly assault on his behalf. This brutal controversy behind him, Vito Marcantonio won the 1946 election and retained his seat with the New York House of Representatives.

Following the murder of Scottoriggio, Anthony Lagana, who worked for Vito’s campaign, was himself killed in 1947 and speculation linked his death to this political turmoil. Lagana may have been a relative of Lucchese capodecina Joseph Lagano, a Calabrian member of the group’s Manhattan faction. Anthony’s birth record uses the Lagano spelling and some records alternately spell Joseph’s name “Lagana”. Both Lagana/Laganos were linked to the same branches of the local Italian underworld as Vito Marcantonio.

An informant told authorities in 1947 that Vito Marcantonio had “the support of semi-gangster elements” in his congressional district, an understatement if Vito was himself a made member. They also learned that members of the Communist Party had been mobilized after the Scottoriggio murder the year previous with the intent of supporting Marcantonio should he be held legally accountable for the man’s death. Like the mafia, the FBI cultivated sources within the Communist Party who provided a wealth of inside information on their inner-workings, though the impact of Communist support for Vito Marcantonio was less immediate than that of Cosa Nostra figures like Coppola, known as “Trigger Mike” in the press.

Vito’s ally Mike Coppola descended from the mainland of Italy, like Marcantonio, and inherited his Cosa Nostra title from Ciro Terranova, half-brother of Giuseppe Morello, who coincidentally visited Sicily with Marco LiMandri’s father-in-law Giovanni Pecoraro in 1922. According to Joe Valachi, Coppola's decina was notorious for excessive violence and multiple generations of Family leaders have come from this historic crew, including Philip "Benny Squint" Lombardo, “Fat Tony” Salerno, and current boss Liborio "Barney" Bellomo, the latter with heritage in Corleone like Giuseppe Morello and Ciro Terranova. Bellomo’s father Salvatore was a Genovese member and there are indications his namesake grandfather was as well.

Vito Marcantonio's underworld relationships extended beyond the Genovese Family and included the other East Harlem Family with roots under Giuseppe Morello, the Lucchese Family. Joe Valachi makes no reference to Marcantonio in his book The Valachi Papers, but in his rambling personal memoir The Real Thing, Valachi states that Lucchese boss Tom Gagliano, another Corleonese, “had” Vito Marcantonio under his aegis. This general terminology can apply to either a made member or associate who is “on record” with the mafia, but it indicates Marcantonio was affiliated not only with Cosa Nostra but specifically the Luccheses.

If Vito Marcantonio was an inducted member as Frank Bompensiero reported, there is no indication Valachi was aware of it, his fleeting reference made in context with other politicians who worked with Cosa Nostra leaders. Neither does Marcantonio surface in the extensive member identifications made by Valachi following his 1962 cooperation. Joe Valachi had blindspots, however, and though the information he provided was extensive and invaluable, it was not a comprehensive view into every Cosa Nostra member in New York and perhaps he was not in a position to know sensitive details like the formal membership of a high-level politician. Pentito Tommaso Buscetta indicated fully-initiated politicians in the Sicilian mafia reported directly to Family bosses and their formal status as Cosa Nostra members was largely kept from rank-and-file members, the latter description fitting Valachi to a tee. In Sicily, these politician members are referred to as uomo d'onore riservato, or “reserved man of honor”, a reference to their highly-secretive membership even within the mafia’s own internal networks.

As a soldier in the Genovese Family, Joe Valachi may not have been privy to the formal role played by a well-guarded mafia politician like Vito Marcantonio. Marcantonio's ties to Fiorello LaGuardia, his own congressional service, and the extensive "overworld" connections he utilized would make his status a private matter best kept among the exclusive ranks of Cosa Nostra leaders rather than “street guys” like the unrefined Valachi. Adding an additional layer of secrecy to an already-secret organization, self-professed East Harlem Lucchese member and FBI informant Carmine Taglialatela, who answered to the Brooklyn-based Paul Vario crew before fleeing to the West Coast, stated that the Lucchese Family cautioned him to avoid talking about his membership even with other fully-initiated members. This philosophy would likely apply to an even greater degree with regard to a powerful public figure like Vito Marcantonio.

The lack of New York sources familiar with Marcantonio's membership status proves a dilemma, though. Why would the West Coast mafia know of Marcantonio's membership while locals like Joe Valachi and countless other New York informants did not? Surely the rumor of Vito Marcantonio's membership would reverberate in New York before reaching California whether this gossip was true or not. Marco LiMandri was a former New York member familiar with Vito Marcantonio’s membership but it is not evident when and where he learned of it, these details emerging while LiMandri resided in San Diego alongside Frank Bompensiero as a Los Angeles member.

The answer may come from Southern California’s relationship with the Lucchese Family. The Lucchese Family represented the Los Angeles Family on the national Commission for nearly 25 years, beginning at its creation in 1931 and continuing until the death of Los Angeles boss Jack Dragna in 1956. Shared Sicilian hometowns and a history in East Harlem likely played a role in this cross-country relationship, with Jack Dragna being born in Corleone like Lucchese boss Tom Gagliano and spending his formative years around Cosa Nostra in East Harlem.

Dragna is believed to have been inducted into the Morello Family in 1914, a year the LA boss reportedly cited when discussing his entry into the mafia with one-time capodecina Jimmy Fratianno, who recounted the information in his memoir. Jack Dragna undoubtedly transferred membership to California by the 1920s much as Marco LiMandri did in later years. That Frank Bompensiero confirmed Marcantonio's name with the LiMandris does show that select New York figures were aware of his alleged membership, Marco LiMandri's history with high-ranking Lucchese members and relation to Giovanni Pecoraro adding additional weight to LiMandri's knowledge of the Lucchese Family’s secrets-within-secrets, but Jack Dragna’s history and intimacy with the Morello and Lucchese organizations could have played a role as well in addition to his ongoing association with Tom Gagliano nationally.

Whether he was truly a Lucchese member or simply a valuable associate, Vito Marcantonio's affiliation with the East Harlem-based mafia environment is further established through his association with Gagliano's underboss Tommy Lucchese, who produced the Family's colloquial name. Drawing attention from the FBI as both a leftist politician and mafia associate, Vito Marcantonio was identified as a close friend of Lucchese by the late 1940s and allegedly assisted the underboss's son in gaining acceptance to the prestigious West Point Military Academy according to journalist Selwyn Raab’s book Five Families. An FBI report confirms this information, describing Marcantonio’s association with Tommy Lucchese and the congressman’s role in the younger Lucchese’s 1947 attendance at the academy.

Marcantonio was also included twice on a 1952 FBI list of Lucchese's “close associates”, first noting Vito Marcantonio and his Park Place residence near New York’s City Hall then listing him again following the names of Marcantonio's friends Mike Coppola and Joseph Coppola of the Genovese Family along with prominent Lucchese members like Eddie Coco and Vincent Rao. Lucchese member Joseph “Lagana” (Lagano) is mentioned as well, bringing to mind Vito’s campaign staffer Anthony Lagana’s 1947 murder, but is nicknamed “Joe Stretch” on the list, perhaps confusing him with Genovese member Joseph Stracci who used that nickname and was active in the garment industry like Lagano. Tommy Lucchese was asked about his relationship with Vito Marcantonio by prosecutors the same year the FBI’s list was produced in 1952, the government alleging Lucchese provided financial contributions to Marcantonio's political efforts.

The Lucchese Family and specifically their highest-ranking members were heavily involved in New York City’s Garment District, Tommy Lucchese himself regarded as one of the most influential Cosa Nostra leaders in the industry who owned interests in multiple factories. Vito Marcantonio was a labor advocate and supporter of trade unions and his political position along with participation in related activism would make for a valuable ally of Lucchese Family interests in these affairs. The degree that Vito Marcantonio may have assisted the Lucchese Family in the garment trade is unknown but the opportunities presented by this arrangement open the imagination to numerous possibilities as to how he was utilized.

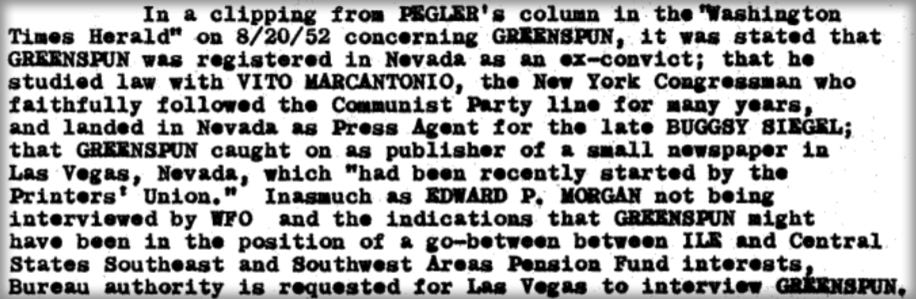

Vito’s network extended to organized crime figures outside the strictly Italian membership of Cosa Nostra, the FBI noting his relationship with ex-convict Herman “Hank” Greenspun, publisher of the Las Vegas Sun who was targeted by the Nixon administration during events linked to the 1970s Watergate scandal. Greenspun was once a Communist like Marcantonio and an FBI report states the two men studied law together — Hank Greenspun was also an avowed enemy of Joseph McCarthy. Greenspun served as Press Agent for Jewish racketeer “Bugsy” Siegel in Las Vegas, Siegel’s links to Cosa Nostra figures being of course well-known to the public.

Available evidence does not provide concrete information on Vito Marcantonio's involvement in racketeering beyond his close relationships with Lucchese and Genovese leaders, but allegations of his association with local mafiosi are confirmed and support Frank Bompensiero and the LiMandris’ perception that Marcantonio was accepted among the ranks of Cosa Nostra. That Vito Marcantonio is linked not simply to made members of the Lucchese Family but specifically the boss and underboss of the Family he was affiliated with shows that he was not relegated to the bottom floor of the organization and enjoyed a special status regardless of what the formalities of the arrangement were. Mike Coppola’s apparent efforts to violently endorse Marcantonio’s congressional election further reveal the extent Cosa Nostra was willing to go to ensure their own man held political office.

Vito Marcantonio was finally defeated by Democrat candidate James Donovan in the 1950 congressional election after twelve continuous years in office, a total of fourteen years when combined with his first term. Marcantonio’s loss was heavily attributed to his vocal opposition to the Korean War in addition to gerrymandering and the combined efforts of Democrat and Republican rivals. Following his departure from the US House of Representatives in early 1951, the East Harlem congressman remained a practicing attorney, living in Washington DC and then returning to New York City where he pursued yet another term in Congress as part of the Good Neighbor Party. Boss Tom Gagliano had died in 1951, the same year Vito Marcantonio's time as a congressman came to a close, and Gagliano was replaced by the Palermo-born Tommy Lucchese, Marcantonio no doubt enjoying the same high-level access noted by Joe Valachi when Tom Gagliano ran the organization.

Younger cousin Gus Marcantonio worked for Vito’s later political campaigns and in the Marcantonio spirit, Gus became active in union affairs and joined the Communist Party. Gus Marcantonio was a longshoreman and influential ILWU Teamster, a rival union to the mafia-controlled ILA on the Brooklyn docks. The Gambino Family and other underworld figures exerted heavy influence on the ILA but the ILWU has no known record of Cosa Nostra association. Gus Marcantonio became involved with the union in 1952, the year after Vito left office, but went to prison in 1953 for dodging the Korean War. What influence, if any, Vito Marcantonio and the Lucchese Family had in Brooklyn labor circles is unknown and though Gus Marcantonio would become more prominent in ILWU after his release from prison in 1955, his mafia-linked cousin Vito Marcantonio was by then a non-factor.

Vito Marcantonio's time under Tommy Lucchese’s official leadership was cut short in August 1954 by a fatal heart attack at the age of 51, thirteen years before Lucchese's own natural death in 1967. Marcantonio was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx and W.E.B. DuBois was among the speakers at his funeral service, the list of pallbearers and other honored guests including reputable figures and no names known to be involved in underworld activity. Marcantonio's Cosa Nostra connections were occasionally referenced in passing throughout the course of his life but Bompensiero's identification of the New York Congressman's formal membership emboldens these footnotes in the larger story of Marcantonio's personal history. Vito Marcantonio was a national politician from New York with close ties to the Lucchese Family, that much is undeniable.

A Politician’s Place in Cosa Nostra

As with Louis Boschetto, we only have one account of Vito Marcantonio's Cosa Nostra membership from a member who never formally met him. While identification of these mafia politicians by reliable FBI member sources does add to the credibility of these allegations, Boschetto has an edge in that Salvatore Costanza was told the US Senator was a point of contact for San Jose members in Wyoming and was tasked with monitoring member Peter Misuraca, then vacationing in Jackson. Contact of this nature is regarded as a duty within the Cosa Nostra network, but Costanza indicated his third-hand knowledge of Boschetto was protected information and he was not in a position to make further inquiries about the US Senator, a sign of the mafia’s general secrecy enhanced by Boschetto’s status in legitimate society. Salvatore Costanza’s anecdote does show Louis Boschetto to be engaged in Cosa Nostra protocol, but in Vito Marcantonio's case we only have a single rumor of his membership and no known instances where he was observed acting in the capacity of a made member, be it criminal or formal.

That both mafia politicians were referenced by fully-inducted members cooperating with the FBI makes it more difficult to dismiss the allegations outright as one might do with an informant of lower status or questionable integrity. Though prone to errors when discussing more nuanced underworld matters outside of their own scope of knowledge, made members are reasonably precise when identifying fellow members. The distinction between an amico nostra and a “mere” associate was essential to the organization’s function and mafia membership is black and white — someone is either a member or they aren't — and members tend to recall these specifics with a high degree of accuracy as they must be constantly aware of who is who when interacting with fellow affiliates of their secret society. Detracting from Bompensiero's account is that he did not personally meet Vito Marcantonio as an amico nostra, but he did make three separate references to Marcantonio's membership over multiple interviews and sought out senior mafioso Marco LiMandri for further confirmation.

Frank Bompensiero was an audacious figure but as an informant he was specific about his knowledge and quite honest, his numerous FBI interviews showing that he was willing to admit when he was not personally aware of someone's Cosa Nostra membership after being prompted with names by his handler. Bompensiero stated openly when he couldn't personally confirm these types of organizational details or when his information was speculative in nature. This was not true with Bompensiero’s multiple references to Marcantonio and Frank strongly believed Vito Marcantonio was a made member, other evidence confirming Marcantonio was at least an associate on record with bosses Tom Gagliano and Tommy Lucchese, both men representing Bompensiero's Los Angeles Family on the Commission.

As with Louis Boschetto's birth in the former Austrian territory of South Tyrol, Marcantonio’s roots in the village of Picerno in Basilicata’s Potenza province pull him away from traditional Sicilian recruitment practices that once drew heavily from blood, kinship, and specific Sicilian hometowns. Boschetto is particularly strange because he was a Northern Italian in Wyoming who likely affiliated with the Sicilian-dominated Colorado Family made up of men from Agrigento, whereas Vito Marcantonio grew up in the Lucchese Family's more inclusive and centralized training ground in East Harlem. Sometimes these non-traditional recruits gained entry by marrying women from Sicilian mafia clans, but in Marcantonio’s case this theory is put to rest by his marriage to the non-Italian Miriam Sanders in 1925.

Though the Morello Family and its spiritual successor the Luccheses were formed by interrelated clans from Corleone and inland Palermo villages, by the late 1910s they were actively recruiting pan-Italian prospects from local neighborhoods and flashy “gangsters” like Dominick Petrilli from Abruzzo became prominent members of the group by the following decade. The Neapolitan-American Joe Valachi would be recruited in turn by Petrilli and later married the daughter of murdered boss Tom Reina from Corleone, with another Reina daughter marrying a Gambino member of mainland heritage. Tom Reina was deceased when his daughter married Joe Valachi but despite some resistance noted by Valachi from the girl’s male relatives, the openness of the Reina clan to non-Sicilian husbands was reflected in the Lucchese organization’s willingness to open its doors to new types of members under Reina’s leadership in the 1920s. The East Harlem mafia was, in a sense, “progressive”.

It does not appear the Lucchese Family factions in East Harlem and the Bronx, where many East Harlem members moved, held the same conservative prejudices more common in the Bonanno and Colombo Families, both of which maintained similarly-sized organizations made up near-exclusively of Sicilians during the era Vito Marcantonio was alive. Though the Luccheses may not have inducted mainlanders in droves during these early years, they were receptive to the idea and Vito Marcantonio's origins may have been a non-factor given his presence in the neighborhood. What separated Marcantonio the most from other Lucchese recruits is that mafia prospects from the mainland typically proved themselves via uninhibited criminality, as Joe Valachi did, while there is no evidence Marcantonio was involved in overt illegal activity and he was already active in grassroots politics by his late teens.

As elaborated on in the previous article on Louis Boschetto, Cosa Nostra was not traditionally concerned with rackets alone but resources of all kinds. This included legitimate professions, trades, and of course politics. Mafia politicians in other cities, Chicago most prominently, were made members and high-level associates, these aspiring political figures providing obvious value to Cosa Nostra’s shadow government. How and when Vito Marcantonio became affiliated with the Lucchese Family is impossible to determine, but just as young men like Joe Valachi caught the eye of mafiosi on the rough streets of East Harlem, Vito Marcantonio may have impressed senior mafiosi through his commitment to East Harlem's insular community and his lofty political goals. Marcantonio had loyalty to his surroundings and, more importantly, initiative.

In his autobiography A Man of Honor, former New York boss Joe Bonanno states that Cosa Nostra is a “microcosm of society at large” and within his Family he at one time carried men from a wide range of professional backgrounds, even citing priests, lawyers, and politicians as members, an assertion that is not supported by names but is indirectly reinforced by his Sicilian mafia lineage and the homeland’s tendency to induct these types of men. The idea that the Bonanno Family inducted politicians into their organization adds to the possibility of the Lucchese Family recruiting one of their own, though there is a strong chance the Luccheses had the only New York mafia politician committed to socialism.

“Sopranos vision” has given casual observers the perception that members and associates of Cosa Nostra are always assigned to a capodecina who issues constant orders and greedily demands tribute from his underlings. This is not necessarily true even when an amico nostra does report to a captain, but the capodecina system is not the only way members receive formal representation. Countless examples throughout mafia history show that members and associates can be assigned directly to the Family administration, usually a specific leader, and the boss himself can have underlings who belong with him only. Joe Colombo had an entire decina under him when he served as a Brooklyn rappresentante but typically it is a select few individuals who answer directly to the Family leadership.

Member or not, it is apparent that Vito Marcantonio was assigned to the Lucchese administration. Joe Valachi placed Marcantonio with Tom Gagliano and other evidence shows Marcantonio had access to Tommy Lucchese before and after Lucchese succeeded Gagliano. As a political figure, Vito was not a racketeer hanging out in “mobbed up” social clubs and would not be expected to maintain his standing through financial contributions or street crime. Not only is “kicking up” money enforced selectively in many Cosa Nostra Families, in some groups or factions it is not required at all and Marcantonio provided resources of greater value than cash alone. Adding to this is another claim from Joe Valachi: initially proposed for membership in the Lucchese Family as an associate of Tom Gagliano’s faction during the Castellammarese War, Valachi maintained a personal friendship with Gagliano even as a Genovese member and stated during his cooperation that the legitimately wealthy Lucchese boss did not take any money from the organization he represented. Within the mafia structure, Marcantonio was likely direct with the boss and offered political influence on behalf of the Family to maintain standing.

Particularly intriguing in the context of Cosa Nostra is Vito Marcantonio's commitment to "extreme leftism", as his ideology was dubbed in the press. The mafia has occasionally flirted with left-leaning causes throughout its known history, with Bisacquino resident Vito Cascio Ferro associating with anarchists and Corleone-based Communist leader Bernardino Verro receiving induction into the Sicilian mafia in 1893. Future New York boss Giuseppe Morello and his step-father Bernardo Terranova were themselves active with the Corleone Family during this period before moving to the United States. That Marcantonio was affiliated with the heavily Corleonese Lucchese Family that spawned from the Morellos and Verro was a member in Corleone itself may be significant, both organizations gravitating toward radical leftists, but the two men had much different experiences with Cosa Nostra.

Bernardino Verro was murdered by the local Family he belonged to in 1915 after he was elected Corleone Mayor. His far-left political causes took precedent over the mafia's own interests and he began to repent his life as a formal affiliate — not even a Cosa Nostra member in elected office like Verro is granted exception to the rules when outside interests eclipse the organization. Similar events occurred several years earlier in Santo Stefano Quisquina, Agrigento, where mafia rappresentante Lorenzo Panepinto was killed in 1911 after pushing his own Communist agenda. Panepinto even tried to spread socialism to the Tampa mafia colony now known as the Trafficante Family during an overseas visit with his compaesani in 1909 and expressed frustration with his American counterparts’ commitment to crime. Just as Verro was an elected official in Corleone, Lorenzo Panepinto sat on Santo Stefano Quisquina’s municipal council. Both men experienced a degree of success in legitimate politics but died the same bloody way many mafiosi do.

A short-lived collaboration between Communists and Sicilian mafiosi occurred after World War II, both groups benefiting from the fall of Fascism, but far-leftism tends to repel the opportunity-minded mafia sooner or later. This was made evident in 1947, when the infamous Portella della Ginestra massacre took place in Piana degli Albanesi, formerly Piana dei Greci, the hometown of Marco LiMandri’s father-in-law Giovanni Pecoraro. Bandits led by Salvatore Giuliano from Montelepre opened fire on a crowd of hundreds parading on behalf of the Italian Communist and Socialist Parties, killing eleven. Communist leader Girolamo LiCausi blamed the mafia and while his Cosa Nostra connections are often overlooked, Salvatore Giuliano was identified by Tommaso Buscetta as a Cosa Nostra member, the two men being formally introduced as such, and Giuliano’s relatives were allegedly members of the Montelepre Family. The bandit leader’s own majordomo, Gaspare Pisciotta, similarly stated that Salvatore Giuliano went through an underworld induction ritual.

The bloodshed in Piana degli Albanesi created a distinct chasm between Cosa Nostra and the left, with later sources noting their incompatability. Colombo member and longtime FBI informant Greg Scarpa told the FBI how the mafia could exist anywhere except Communist countries and indeed most American mafiosi tend to favor right-wing politics today, Cosa Nostra itself being a conservative-minded organization resistant to internal and external change alike. The mafia is fundamentally apolitical in the sense that it favors self-interested opportunism over ideological principles but at its core Cosa Nostra is incompatible with progressive values. Cosa Nostra's mortal enemy is federal intervention and regulation, its ideal environment being one of social conservativism and perhaps economic libertarianism, qualities that allow the mafia's ethno-centric shadow government to impose its values and thrive.

With the Cold War not yet in focus and contemporary socialism still evolving, the Lucchese Family likely saw the value of an Italian politician from East Harlem regardless of his exact philosophical leanings and non-traditional heritage. If Vito Marcantonio provided the organization with a unique opportunity and potential advantage, his specific politics may have been of no concern in the face of other measurable benefits. Marcantonio was a labor advocate and community activist, both areas of interest that could logically interlock with Cosa Nostra’s penetration of labor unions and local influence. More likely, though, East Harlem’s mafia politician was a willing adherent of the mafia subculture who opened the doors to an assortment of multi-pronged opportunities unavailable to recruits involved only in bootlegging, gambling, extortion, and for that matter most legitimate industry. His role was not entirely out of place in the mafia tradition, it is only a matter of who facilitated his entry into the organization’s inner circles and when that took place — questions we cannot currently answer.

If Vito Marcantonio was a member or associate of the Lucchese Family by 1931, when the Commission was formed and closed the organization’s books to new members, Vito’s mafia affiliation would have predated his political career. If he was already initiated by 1935, he would have been a made member throughout his service as a sitting US Congressman. It's possible too that Marcantonio was inducted when the books re-opened in the mid-1940s, meaning he officially joined Cosa Nostra while actively serving with the House of Representatives. In either case, Marcantonio was one of few known Italian politicians confirmed to have been on record with a New York Family and tenured members like Frank Bompensiero and Marco LiMandri believed him to be a confratello in their exclusive organization.

Mainland Heritage & Chicago Connections

Despite fully-initiated politicians being largely a Sicilian phenomenon throughout Cosa Nostra history, at least five mafia politicians in the United States were of mainland heritage. Most of these American politicians did not descend from an underworld lineage but rather proved their organizational value locally through their own initiative rather than bloodlines and clan connections. The examples of this phenomenon available to us at present were contemporaries of Vito Marcantonio.

In Chicago, John D'Arco was a Member of the Illinois House of Representatives between 1945 and 1952, overlapping with Vito Marcantonio’s final years of service in the New York House of Representatives. D'Arco also served as an Alderman and First Ward Democratic Committeeman in addition to an equally presitigious appointment: membership in the Chicago Family, where like Marcantonio he associated directly with the organization's top leaders. D'Arco's family descended from Salerno, Campania, up the coast from Naples, and he was close to fellow Chicago member Pasquale “Pat Marcy” Marciano, a Neapolitan-American who directly engaged in politics alongside D’Arco. Another member of the Chicago Family was Vito Marzullo, who served as Alderman of the West Side 25th Ward, and his family came from Avellino in Campania.

Fred Roti was another politician identified by the FBI as a made member of the Chicago Family and he served as both an Illinois State Senator and Alderman. Roti was a peer of Chicago’s other confirmed mafia politicians and his parents descended from Vibo Valentia province in Calabria. Fred’s father Bruno Roti was a powerful Chicago mafia leader, showing that even one of the group’s political figures could become a second-generation member “despite” his atypical profile and mainland Italian background. In Chicago this was par for the course, where a variety of Italians coexisted in close proximity much like East Harlem and formed close relationships with Sicilians early in American mafia history.

Earlier Chicago mafia figures were themselves involved in politics both directly and indirectly, including Antonino D'Andrea, Michele Merlo, and Joe "Diamond" Esposito, among others. Esposito was from Campania like D'Arco, Marcy, and Marzullo, while the other two men, both Family bosses, were Western Sicilian. Antonino SanFilippo, another Sicilian, served as Alderman in Chicago Heights as well as rappresentante of a small Family there that was later merged with the broader Chicago Family. An American-born mafia politician with Sicilian heritage closer in age to later mafia politicians in Chicago was Joseph Bulger, true name Imburgio, a practicing lawyer with suspected membership in the Family who served as Melrose Park Mayor when he was only twenty-one. Bulger/Imburgio’s family, who sometimes used the Imburgia spelling, came from Campofelice di Roccella in Palermo which directly borders Antonino SanFilippo’s hometown of Lascari, the same village future Chicago boss Joseph Aiuppa’s family came from.

The Chicago Family's enduring influence and control over local politics are well-documented spanning decades and the induction of Italian-American politicians reflects how inseparable the local mafia was from Chicago's corrupt political practices. They also show how even non-Sicilian political figures were able to gain the trust of local underworld leaders and become inducted members, just as Vito Marcantonio was rumored to have done in East Harlem. East Harlem was a neighborhood and Chicago was an entire city but the Cosa Nostra organizations in these locations followed similar trends.

D'Arco, Marcy, and Marzullo's roots in Campania and Roti’s Calabrian heritage place them in Southern Italy and though this separates them from the Sicilian roots of the organization, Campania and Calabria did lend themselves to the mentality of Cosa Nostra through both proximity and the existence of the Camorra and ‘Ndrangheta, the mafia’s mainland cousins. Recruitment from these regions was common in major US cities when pan-Italian underworld relationships began to congeal.

Louis Boschetto of Wyoming was from Germanic South Tyrol and a true anomaly even in the American mafia, but Vito Marcantonio's family background in Basilicata is more neutral, not being part of core Southern Italian underworld traditions but still bordering Campania and Calabria. It was not common but it is neither unheard of for American mafiosi to have roots in Basilicata and in Italy one would have to pass through Basilicata and specifically Potenza province to travel between Campania and Calabria. Chicago had a large concentration of immigrants from Potenza and this province also had colonies in Upper Manhattan.

Confirmed links between Vito Marcantonio and Chicago do exist. A 1959 conversation between Chicago boss Sam Giancana, underboss Frank Ferraro, and high-level associate Murray Humphreys made reference to Marcantonio and Tommy Lucchese. Humphreys, a non-Italian confidant of the Chicago leadership, recalled a story involving both men and conversed about Vito Marcantonio’s political influence. Humphreys seems to quote Marcantonio and/or Lucchese in the anecdote but it is difficult to differentiate between who is being referred to.

Murray Humphreys states that Vito Marcantonio said he had four offices which were “open to anybody” and describes how “They were all Commies,” apparently a reference to Marcantonio or his constituents. Humphreys, known as “the Camel”, references Tommy Lucchese and a visit to Vito Marcantonio’s home, which Humphreys describes as a “junky old house”. He appears to quote either Marcantonio or Lucchese as saying, “I live like a Commie and everybody thinks like a Commie, but that’s how I got my vote,” though it is more likely he is drawing back to Marcantonio speaking as the nature of the statement fits him better. Regardless of who spoke, it implies Vito Marcantonio utilized his socialist image to cultivate public support and the tone of Humphreys’s story is not only cynical but said in context with a discussion of the Chicago Family’s own political practices. The conversation between Giancana, Ferraro, and Humphreys is further evidence of Vito Marcantonio’s close association with Tommy Lucchese and it is particularly relevant because Frank Ferraro and Murray Humphreys were primarily concerned with managing and directing Chicago’s political tentacles.

Vito Marcantonio’s connection to Chicago figures went back further, too. Following the 1943 conviction of Chicago Family leaders Louis Campagna, Paul Ricca, Philip D'Andrea, Charles Gioe, Francis Maritote, and powerful Los Angeles member John Roselli in the infamous “Hollywood extortion” case, the 1950 book Chicago Confidential by Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer states that Vito Marcantonio was hired as an attorney for one of the men, though it is not specified which one. The book is careful to note that this occurred after the trial and the authors hint that Marcantonio’s representation of one of the figures had a specific purpose.

A passage immediately preceding the reference to Vito Marcantonio notes that one particular Chicago lawyer, representing Paul Ricca, was used to facilitate communication between the Chicago leaders and top associates still on the street. Ricca’s attorney and apparent messaggero was the same Joseph Bulger/Imburgio who once served as a Chicago area mayor and is believed to have been a Cosa Nostra member himself. Bulger’s brother Nick was active with the organization in partnership with Paul Ricca, chairman of the Family consiglio, and their first cousin Charles “Murgie” Imburgia, a variation on Imburgio, eventually became a high-ranking Pittsburgh Family member. Joseph Bulger used his attorney-client privilege to carry messages between the legally compromised leaders and Tony Accardo, who became Chicago Family boss as a result of the case, as well as Murray Humphreys.

It’s possible Humphreys’s 1959 memory of meeting with Vito Marcantonio was related to these 1940s events given Marcantonio’s ties to the case. If Vito was a member at this time it opens the possibility that he, like Bulger, carried sensitive messages relevant to the organization on behalf of Chicago Family leaders. The important role of John Roselli from Los Angeles in the case brings to mind Frank Bompensiero and gives Frank’s perspective on Vito Marcantonio more weight. Bompensiero was a close friend of Roselli, who later transferred membership to Chicago while remaining in California, and the two men formed a treacherous faction in Los Angeles along with Jimmy Fratianno that confided in one another and actively plotted against the local Family leadership. Roselli may be yet another source who provided Bompensiero with information on Vito Marcantonio’s ties to Cosa Nostra based on their mutual involvement in the “Hollywood extortion” case.

Cosa Nostra has a long history of utilizing attorneys as middlemen and the Sicilian mafia has included many lawyers among its formal ranks. In the United States, Frank Bompensiero’s boss in Los Angeles at one time was Frank Desimone, the son of a previous Family boss and a licensed attorney who once represented underworld figures. Vito Marcantonio was a lawyer at the time of the “Hollywood extortion” case, but Marcantonio was also a sitting congressman and his willingness to provide legal assistance to a Cosa Nostra figure in Chicago is evidence of his ongoing commitment to the national mafia even while in office. This arrangement was no doubt approved if not encouraged by Lucchese Family leaders Tom Gagliano and Tommy Lucchese, especially given it involved John Roselli and Los Angeles, an organization they represented on the Commission. Whether Marcantonio and Lucchese’s involvement with Murray Humphreys was connected to the “Hollywood extortion”, their ties to a powerful Chicago associate on record with the Family leadership all but confirms the Lucchese Family’s blessing in matters concerning Marcantonio, Chicago, and California.

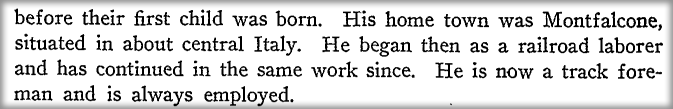

Murray Humphreys’s reference to Vito Marcantonio in the 1959 conversation with boss Sam Giancana must have brought to mind a familiar name in the latter’s own personal history. An early associate of Giancana was Rocco Marcantonio, both men participating in the notorious “42 Gang” before Giancana rose through the ranks of Cosa Nostra. A connection to Vito Marcantonio is unlikely, though, as Rocco Marcantonio told an interviewer his heritage came from “Montfalcone” in “central Italy” and records suggest his family descended from Montefalcone di Val Fortore in Campania’s Benevento province.

Vito’s family background in the village of Picerno in Basilicata’s Potenza province places their origins a significant distance from one another but it is essential to explore possible connections of this nature even if it’s only to rule them out. However, Vito Marcantonio was linked to the Monte Vulture Social Club in New York across the street from his office and he represented men from this club charged with gambling on one occasion, Monte Vulture sounding similar to Rocco’s ancestral hometown of Montefalcone. Monte Vulture is a village in Potenza near Vito Marcantonio’s ancestry in Picerno and is an odd coincidence if nothing else, but shows him to be connected to local gamblers from Basilicata like him who operated in close proximity.

Just as John D'Arco represented Illinois as a congressman during the same period Vito Marcantonio served in New York City in the 1940s and early 1950s, Louis Boschetto's time as a Wyoming State Senator made him another contemporary mafia politician in national office at the time. Boschetto made documented travels to Chicago but no evidence has surfaced directly linking him to the Chicago Family's politicians, nor is there evidence of association between Vito Marcantonio and any of these men. There is a degree of likelihood that members of this political class of Cosa Nostra were aware of one another and with regard to Chicago it is almost guaranteed some of their mafia politicians knew of Marcantonio based on his connection to Murray Humphreys and the “Hollywood extortion” case.

Mafia politicians represented a small, exclusive facet of the Italian-American underworld and had more in common with one another than they did most members within their own respective organizations. The men cited here were of mainland heritage and held high political office, making affiliation with Cosa Nostra anything but obvious to outsiders. This was a feature, not a bug, and it’s possible Sicilian-Americans in these same positions would have drawn more suspicion given the public’s tendency to associate heritage from the island with Cosa Nostra.

Conclusion

I approach FBI reports as well as any information on this subject with a degree of reservation. We can only analyze what is currently available and use context to further corroborate claims that often have few sources. There are no other accounts confirming Vito Marcantonio to be an initiated member of Cosa Nostra beyond Frank Bompensiero, though it is evident Bompensiero did not invent the name "Marco Antonio" nor his position as a former US Congressman in New York. Bompensiero was referring to Vito Marcantonio.

Marco LiMandri was apparently more familiar with Marcantonio’s formal membership although he was not an informant and thus his perspective was channeled through Frank Bompensiero, as was Bompensiero’s belief that Jimmy Fratianno had specific knowledge of this individual. LiMandri’s account is given credibility due to Vito’s affiliation with the Lucchese Family, an organization LiMandri was heavily linked to. Unlike LiMandri, Fratianno did cooperate with the FBI, becoming a Cooperating Witness in the years after Frank Bompensiero’s 1977 murder. Jimmy’s decision to “flip” required him to tell authorities everything he knew and he wrote two autobiographies in addition to giving public interviews. He did not, to my knowledge, mention Vito Marcantonio nor identify him as a member.

The mind of a seasoned Cosa Nostra member is filled with names, places, and connections often dating back to young adulthood if not childhood. When a member cooperates, what we are told tends to focus on dominant relationships in the man’s life and the anecdotes he shares vary wildly depending on context. He may know more about a given person or subject but without the right prompt simply doesn’t think to bring it up. I’ve experienced this in conversation with former Cosa Nostra figures, where the mention of a certain detail can bring forth a wealth of information that might not have been relevant to his cooperation, public interviews, or published accounts.

Jimmy Fratianno should have remembered the Cosa Nostra membership of a US Congressman if indeed he knew about Vito Marcantonio as Frank Bompensiero believed Fratianno did, but like Bompensiero he may not have met him and thus saw no reason to discuss him publicly. Perhaps there is a reference hidden in Jimmy’s 302 interviews with the FBI but as it stands right now we can’t use his cooperation to confirm or deny Vito Marcantonio’s membership. Frank Bompensiero is our primary source and to that end he isn’t a bad one. Bompensiero might in fact be my first choice if I had to choose one informant to rely on for word-of-mouth gossip.

The strong relationship between the Lucchese and Los Angeles Families adds to the possibility that Vito’s membership was known by select California figures, much as select figures in San Jose knew of the obscure Louis Boschetto through their own connections. Frank Bompensiero and Jimmy Fratianno’s time as Los Angeles Family captains under Jack Dragna shows them to be trusted members at one time who may have received information not readily spoken about among the broader amici. Though he never gained a rank above soldier, the same is true for Marco LiMandri based on his relation to top leaders of the Morello Family, which predated the Luccheses, and other relationships to key New York-New Jersey and Los Angeles mafia figures.

Frank Bompensiero is an extremely high-quality source and his identification of made members is unpretentious and explicit. His understanding of the distinctions between different organizational roles and their corresponding status draws little to no criticism from researchers, though his lack of direct involvement with Vito Marcantonio makes his identification of Marcantonio's membership an allegation rather than a definitive fact. It is valuable gossip that passed through made members, these men more trustworthy than a Family associate, and Bompensiero was aware of Marcantonio's membership through conversations with members he trusted to relay this information accurately.

This article utilized other sources who revealed Vito Marcantonio’s association with high-ranking Cosa Nostra figures, particularly in East Harlem, providing at least circumstanial support of Frank Bompensiero’s information. Joe Valachi was aware of Marcantonio’s association with Tom Gagliano and the FBI documented the congressman’s friendship with Tommy Lucchese, while Genovese capodecina Mike Coppola was linked to an election-related murder committed on behalf of Vito Marcantonio’s 1946 campaign. If Marcantonio did represent one of the Chicago Family leaders circa 1943, his association with the highest levels of the organization extended to other cities and he utilized his legal profession and political credibility to assist the mafia at large.

The alleged membership of multiple politicians in Chicago, Wyoming, and New York City opens further questions about the extent that Cosa Nostra infiltrated ostensibly legitimate politics during its dark early years. These men held significant political office, even becoming US Senators and Congressmen, but the Sicilian mafia was much more notorious for infiltrating municipal and even federal politics, opening the possibility of other mafia politicians in the United States who were kept secret from the public and perhaps most of the mafia's own members. Brooklyn rappresentante Joe Bonanno stated that his Family included formally-inducted politicians as well. Without reputable FBI informants, wiretaps, and memoirs it is next-to-impossible to identify these unlikely members, but references to mafia politicians like Marcantonio, Boschetto, D'Arco, Marcy, Marzullo, and Roti within the ranks of Cosa Nostra are invaluable to mafia research.

Vito Marcantonio's diehard socialism and apprenticeship with the lauded Fiorello LaGuardia raise further questions about New York City's political history. Available evidence does not cast a mafia shadow over LaGuardia's legacy but his relationship to Marcantonio shows that he was within one degree of Cosa Nostra himself and may have benefited from these shadowy allies in select neighborhoods at one time despite his public opposition to organized crime and specifically the mafia. With this in mind, LaGuardia arrived back in New York from Montreal in January 1945 and among the plane’s other passengers, eight total, was a Paul Carbo, age 40. Further investigation suggests this was notorious boxing manager and Cosa Nostra member Paul “Frankie” Carbo. Carbo is often erroneously included on lists of Lucchese members due to his close relationship with that Family but he was in fact a member of the Genovese, the other Family the Lucchese-affiliated Vito Marcantonio closely associated with.

Why LaGuardia traveled with Carbo in 1945 is unknown but it adds to the possibility that the celebrated mayor was himself no stranger to mafia figures. Corleonese genealogist Justin Cascio also discovered that Lucchese consigliere Vincent Rao’s niece, the daughter of his mafioso brother Calogero, was married to Fiorello LaGuardia’s close associate Alfred Santangelo, a former New York Assistant District Attorney, while another of Calogero Rao’s daughters married Santangelo’s brother George, a doctor. Another Santangelo brother, Robert, was an attorney who represented the Raos’ relative Joseph Gagliano in his 1946 narcotics trial.

The Santangelos were part of LaGuardia’s inner circle much as Vito Marcantonio once was and they complement Marcantonio’s ties to the Lucchese Family. Marcantonio was campaign manager for LaGuardia’s congressional run and it is easy to imagine Vito Marcantonio and the Santangelos utilized their Cosa Nostra contacts to benefit LaGuardia in some capacity, much as an FBI informant reported the Communist Party’s support of LaGuardia through his relationship to Marcantonio. Vito Marcantonio used these contacts for his own political campaigns as evidenced by the Scottoriggio murder.